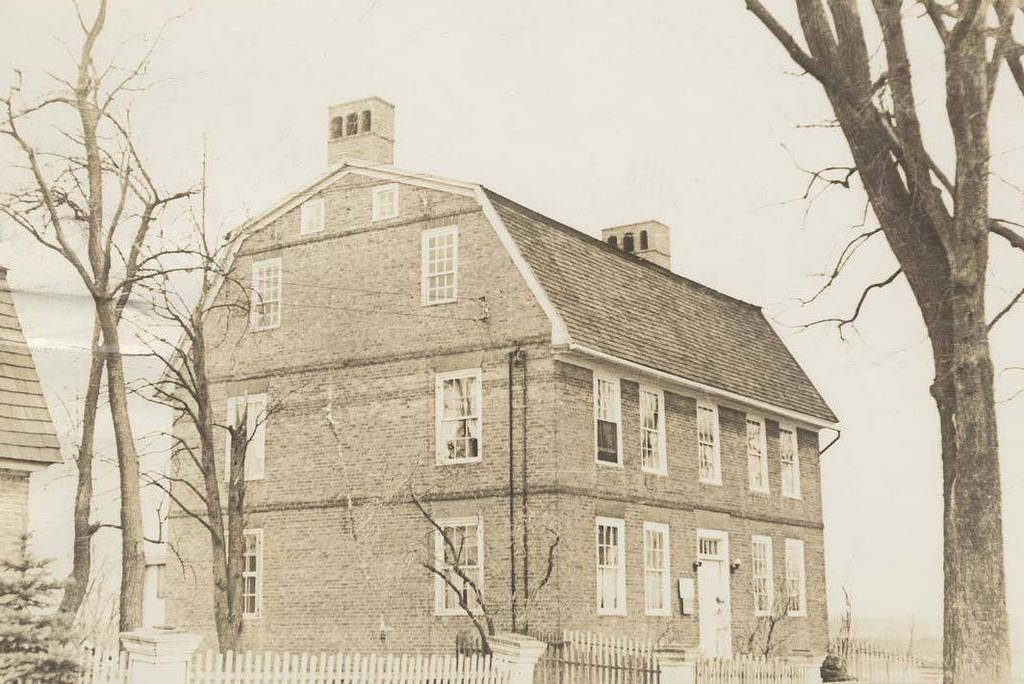

The house at 128 Hayden Station Road in Windsor, around 1935-1942. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

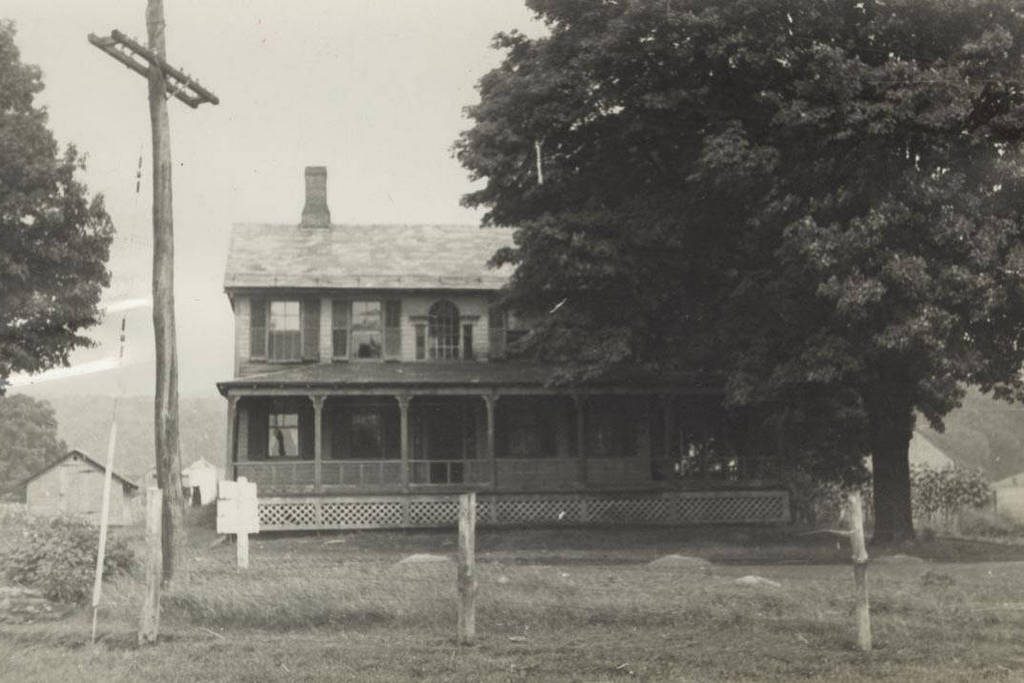

The house in 2017:

Brick colonial houses are not particularly common in rural New England, but the town of Windsor has an unusual number of such homes that are still standing. This particular house was built around 1763 by Nathaniel Hayden, whose great-great grandfather William Hayden had settled in this area of Windsor more than a century earlier. Nathaniel had grown up across the street from here in his father’s house, but when he was 24 he married Anna Filer, and the couple moved into this new house around the same time.

Like his father, Nathaniel was a farmer, shoemaker, and tanner, but he also served as a captain in the town militia. At the start of the American Revolution, he led a group of 23 Windsor men who marched out following the Lexington Alarm, and he later served as a captain in the Continental Army, where he participated in the Battle of Long Island. However, tragedy struck the Hayden family in early 1776, when Nathaniel’s wife Anna died, at the age of 35.

Two years after Anna’s death, Nathaniel remarried to Rhoda Lyman. He had no children from his first marriage, but he and Rhoda had four children together: Nancy, Nathaniel, Naomi, and Pliney. Nathaniel lived here until his death in 1795, at the age of 57, but the house would remain in his family for many years. Rhoda outlived her husband by nearly 40 years, and lived here along with the younger Nathaniel and his wife Lucretia, whom he married in 1808.

Nathaniel and Lucretia had five children, all sons, who grew up here in this house. Two of their sons, Nathaniel and George, moved out of this house after their marriages, but remained in the Windsor area. Two others, Edward and Uriah, traveled to California in 1849, seeking their fortunes in the Gold Rush. Like most of their fellow Forty-Niners, though, they only had moderate success. Edward would remain in California, but Uriah eventually returned east, where he lived in New York state.

Of the five sons, only the youngest, Samuel, remained here in the family house. He was only nine years old when his mother Lucretia died in 1831, but he lived here with his father and his uncle Pliney, eventually caring for both men in their old age. He married his wife, Sarah L. Halsey, in 1849, and they had one child, Lucretia, who was born in 1851 and named for her grandmother. Nathaniel died in 1864 at the age of 83, and Pliney lived here until his death 11 years later at the age of 89, after having been blind for the last few years of his life.

Lucretia married in the early 1870s, but was widowed at a young age, and by the 1880 census she was living here in this house with her parents. Samuel would remain here in this house until his death in 1900, and his wife Sarah died eight years later. Lucretia appears to have continued to live here for the next decade, until her death in 1918. She had no children, so her death marked the end of over 150 years and four consecutive generations of ownership by the Hayden family.

By the time the first photo was taken around the late 1930s, the house was owned by Willard Drake, a mason whose property also included the neighboring John Hayden House. At the time, it was already recognized as a historically-significant home, and very little has changed in this scene since then. Now over 250 years old, the Nathaniel Hayden House still stands as a good example of a brick, Georgian-style home, and it was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.