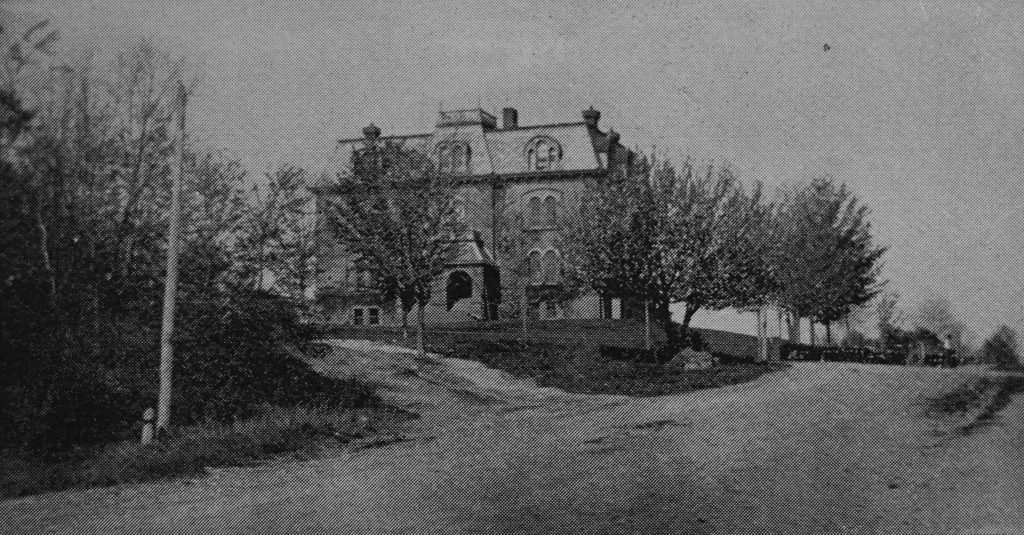

The Myrtle Street School in the Springfield neighborhood of Indian Orchard, seen from Worcester Street near the corner of Myrtle Street, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2017:

Prior to the Civil War, Springfield lacked a strong centralized school system. The city was divided into 12 school districts, each of which was responsible for taxing residents, hiring teachers, setting curriculum, and maintaining schools. However, this proved inefficient, in part because these school districts tended to focus more on lowering taxes than improving education, and by the late 1860s school committee member Josiah Hooker had led a large-scale reform of the city’s public schools.

The result of these reforms was a new high school building on State Street, plus six new grammar schools around the city. All were located in or near the downtown area except for the Indian Orchard school, which was located here at the corner of Worcester and Myrtle Streets. Located in the far northeastern corner of the city, Indian Orchard developed as a factory village in the mid-19th century. It saw a significant population growth during this time, particularly among French-Canadians and other immigrant groups who came to work in the mills, so a grammar school became necessary to serve the needs of the village.

At the time, students attended primary school for three years, followed by six years of grammar school and then four years of high school. The 1884 King’s Handbook of Springfield provides a description of the grammar school curriculum, writing that “In these schools, thorough instruction is given in all the common English branches, including book-keeping, and United-States and English history; and special teachers give instruction in penmanship, music, and drawing.” Following the reforms of the 1860s, the school year began on the first week of September and ended on the Friday before July 4, and students attended school from 9:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m., with a two-hour break from noon to 2:00.

The Indian Orchard school was completed in 1868, and it was designed by James M. Currier, a local architect whose works included three other schools in Springfield, along with an assortment of factories, business blocks, and houses. Perhaps his most notable commission, however, was a house in Ottawa, Canada, that he designed for his brother, Joseph M. Currier, who was a lumber dealer and Canadian politician. This house, located at 24 Sussex Drive, now serves as the official residence of the Prime Minister of Canada, although it has been heavily altered from Currier’s original design.

Like the Prime Minister’s residence, though, the Indian Orchard school has also been extensively modified over the years. The first photo shows its original appearance, with its mansard roof and Second Empire-style architecture, but by the turn of the 20th century this building had become too small for the growing population of the village. As a result, in 1904 a large wing was built on the west side of the original building, facing Myrtle Street. This is the part of the school building that is visible in the present-day photo, and features a Classical Revival-style design that was the work of architect Eugene C. Gardner. The addition hid the original school building from this angle, although it is still standing and still visible from the other side of the school.

This expansion added eight classrooms to the school, but within a decade there was again need for more space, and in 1914 Gardner was hired to design a matching, nearly symmetrical wing on the south side of the building. Located on the left side of the 1904 addition, just out of view from this angle, the new wing doubled the size of the building. It was completed in 1915, and included eight more classrooms, plus a lunchroom, gymnasium, and an auditorium that could seat nearly 700 people.

The school, which became known as the Myrtle Street School after the additions, remained in use until the early 1980s. Like several other historic Springfield school buildings, it has since been converted into condominiums, and is still standing with few significant exterior changes. Even the original 1868 section is still there, and it now stands as the oldest existing school building in the city, as well as the only one of the original six grammar schools that is still standing. Because of this, the building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.