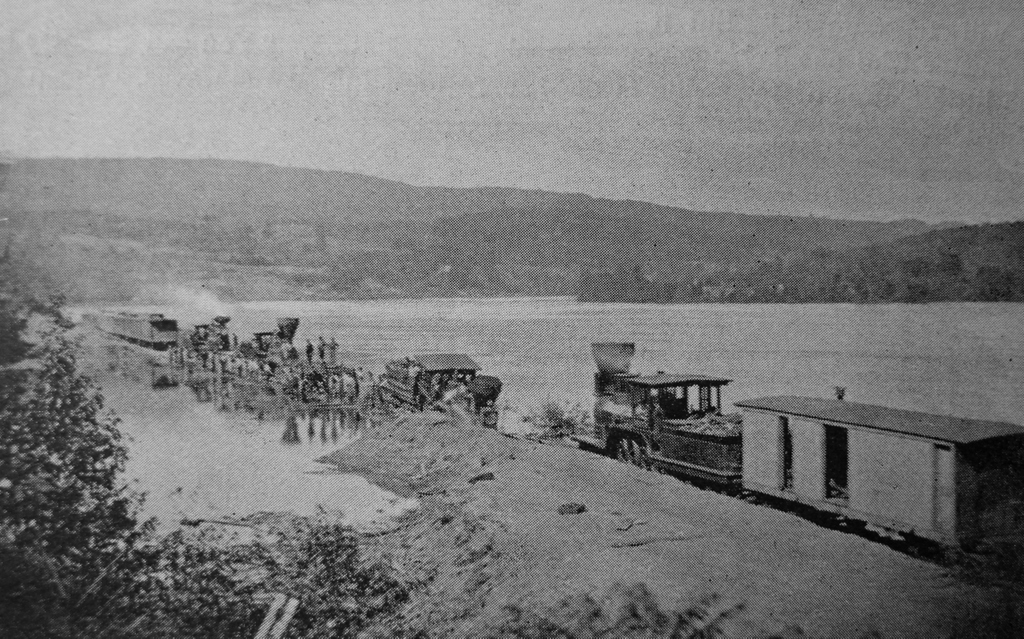

A train wreck at Jones Point in Holyoke, Massachusetts, probably on July 24, 1869. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

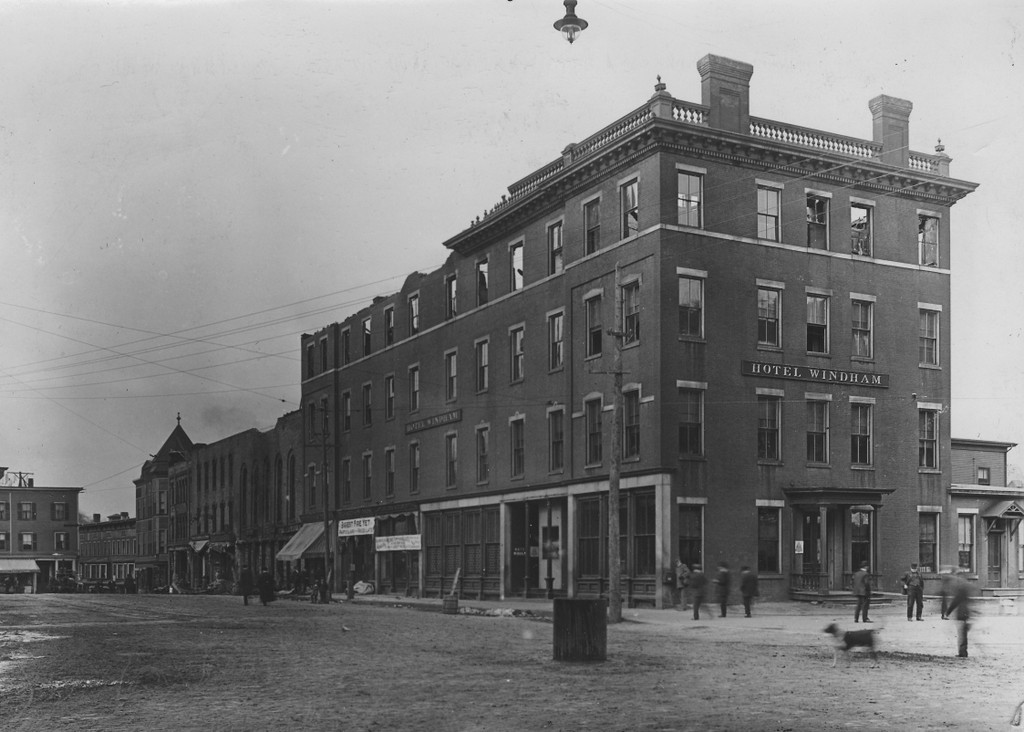

The scene in 2025:

These two photos show a site on the west bank of the Connecticut River that is known as Jones Point. It is just north of the modern-day Jones Point Park, and historically this was the far northern edge of Holyoke, before the city annexed Mount Tom and the Smith’s Ferry neighborhood in 1909. As shown in these two photos, a railroad track runs along the riverbanks. Opened in 1845 as the Connecticut River Railroad, it linked Springfield to Northampton, and was later extended north to the Vermont border.

The top image is from the book Picturesque Hampden, which was published in 1892. It was accompanied by the caption “A Railroad Wreck at Jones’ Gap,” but it did not otherwise have any identifying information, such as the date or the circumstances of the wreck. However, it may have been the train wreck that occurred on July 24, 1869, when a southbound Connecticut River Railroad passenger train derailed, injuring three crew members. Newspaper accounts did not specifically identify Jones Point as the site of the accident, but it was described as having occurred about two miles north of Holyoke, which would place it in this section of the track.

Initial reports indicated that the train had derailed after striking a stone from a nearby quarry that had fallen onto the tracks. However, later accounts blamed the quarry’s own railroad, which crossed the main tracks here. The quarry’s tracks were set slightly higher than the mainline ones, supposedly causing the locomotive’s wheels to strike it and cause the derailment. Regardless of the cause, though, the accident could have been much worse. As it turned out, no lives were lost in the accident, and none of the passengers were injured.

The July 26, 1869 edition of the Springfield Republican provides a description of the wreck:

Saturday was an eventful day in railroad travel in this vicinity, two serious accidents occurring on the northern routes, one near home and another in Vermont. The former occurred in the morning to Conductor Fleming’s train from the north over the Connecticut River railroad, between Smith’s Ferry and Holyoke, at the cross track from the stone quarry leading down to the river. While running at full speed the engine was thrown from the track by a stone between the cross and main tracks, and ploughed along some three rods upon its side. The engineer, Henry H. Snow of Brattleboro had his right leg broken in two places, and his knee split open. Amos Mosher of Mitteneague, the fireman, was bruised in the back, and Frank Kingsley of South Vernon, forward brakeman, had his left ankle sprained. None of the passengers were injured, although the greatest alarm and consternation prevailed among them. A special train, with Drs Breck and Rice, with mattresses, etc., was immediately dispatched to the scene of the accident, and brought the injured persons to this city. Snow’s leg was set by Dr Breck, who accompanied him to Brattleboro, in the afternoon. The doctors do not regard the injuries of the fireman and brakeman as serious. Under all circumstances it seems almost miraculous that a large number of lives were not lost.

Richard Brown, Conductor Fleming’s trusty head brakeman, who was at his usual post on the rear car of the train, was unharmed. His first thoughts were for his brother brakeman, Kingsley. This man had showed remarkable coolness. The car platform was broken and fell from under his feet. He supported himself by hanging to the knob of the car door. Notwithstanding this precaution he was caught between the cars and severely jammed. In this condition Brown found him. “Dick,” said he, “if any one else is hurt worse than I am, help him first!” At this Brown went to the assistance of Engineer Snow, whom he found lying several rods distant. Harley, the well known newsboy on the train, experiences a severe tumbling. He turned a summersault in the aisle of one of the cars, but picked himself up with only a bruise on his head. The conductor was busy caring for his hurt assistants. The force on that train seem to each other like brothers, and they would almost die for each other.

The wreck above Holyoke was cleared from the track so as to let the afternoon train going north pass at 4 o’clock; but nothing further was done than simply to make room for trains to run by. It was a sad sight, the proud “iron horse.” “North Star,” slain and prostrated on its back; the smoke-stack lying at a distance, and its neck driven into the sand. On Sunday it was righted up and, just able to crawl, was led down and stabled in the repair shops of the road in this city, where it was visited during the early evening by many people. The tender and cars were also brought down. The platforms of the cars are badly smashed and the tender is a total wreck.

Based on this account, it appears that the top photo may have been taken on the day after the wreck, since the one in the photo is sitting upright. However, the locomotive appears to have its smokestack attached, which does not match the description in the newspaper, unless the smokestack was reattached when the locomotive was righted. So, while it seems likely that the top photo was taken of this particular wreck, it is hard to say this with certainty.

Several decades later, this site at Jones Point would be the location of another railroad accident, although this second one had deadlier consequences. It occurred on January 27, 1888, when a group of railroad workers were shoveling snow drifts off the track. They had cleared one track, and were working on the other track when a train passed through here on the cleared track without any warning. Heavy winds and drifting snow made visibility poor, and neither the engineer nor the workers could see each other until it was too late. Three of the workers were killed instantly, and a fourth was badly injured and died soon afterwards. Newspaper accounts do not give the precise location of this accident, but they indicate that it happened “at Jones’s cut, some two miles above Holyoke.”

Today, more than 150 years after the top photo was taken, not much has changed in this scene aside from the tree growth. The railroad is still here, and it carries freight trains along with Amtrak passenger trains, including the Vermonter to St. Albans and the Valley Flyer to Greenfield. The land here is now owned by the city of Holyoke, and it is part of Jones Point Park.