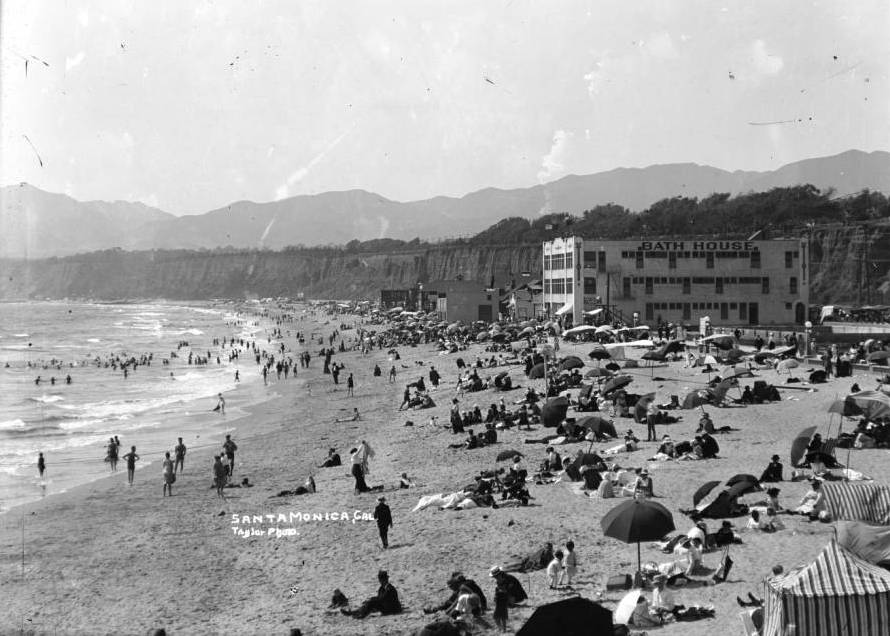

Looking north from the Santa Monica Pier in Santa Monica, California, around 1905. Image courtesy of the University of Southern California Libraries and the California Historical Society.

The view in 2015:

These views shows Santa Monica looking north from the pier along the Palisades, the steep cliffs separating the city from the beach below. When the first photo was taken over a century ago, Santa Monica had already become a popular beach resort.. At the time, the area above the Palisades was still sparsely developed, but there were number of amenities along the beach, including a bath house that offered visitors the option of swimming in a heated indoor pool rather than the relatively cool ocean. The beach was crowded on this particular day in 1905, with the attire of the visitors reflecting the styles of the time, including men in dark suits and straw hats, women in long white dresses, and swimmers dressed in nearly full-body bathing suits.

Today, not much is left from the original photo except for the Palisades. Even the beach itself has been extensively altered and widened, and a large parking lot now sits on this spot. In the distance, hidden from view, the Pacific Coast Highway now runs along the bottom of the Palisades, beneath the modern hotels and condominium buildings that now line Ocean Avenue on the top of the cliffs.

This post is part of a series of photos that I took in California this past winter. Click here to see the other posts in the “Lost New England Goes West” series.