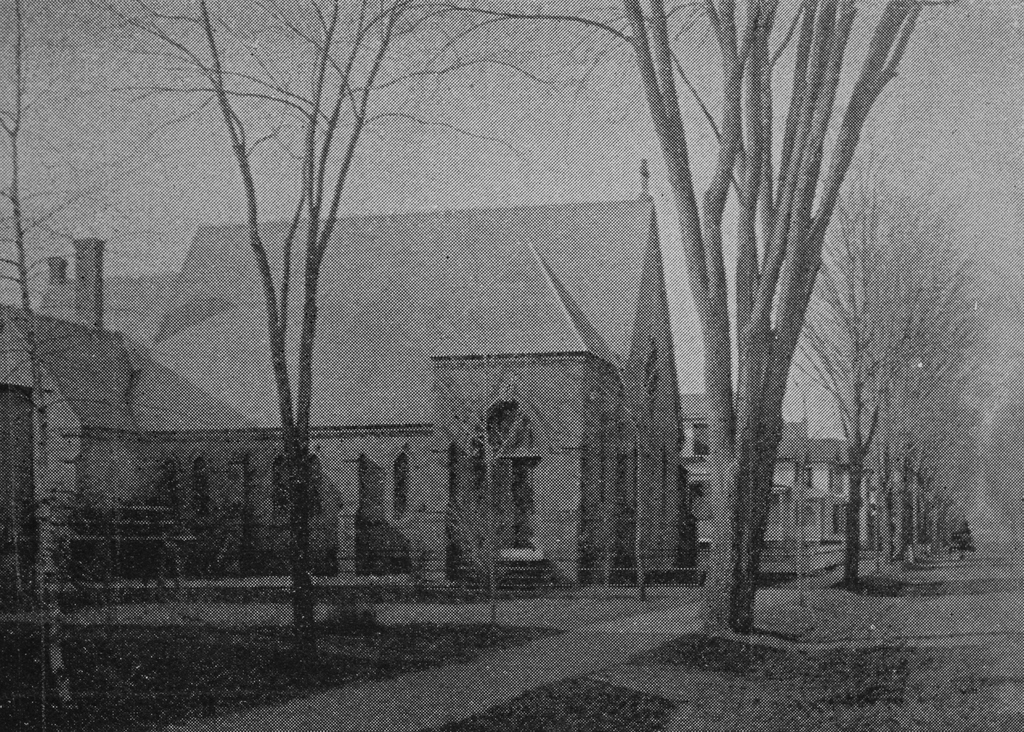

The Civil War monument at Park Square in Westfield, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

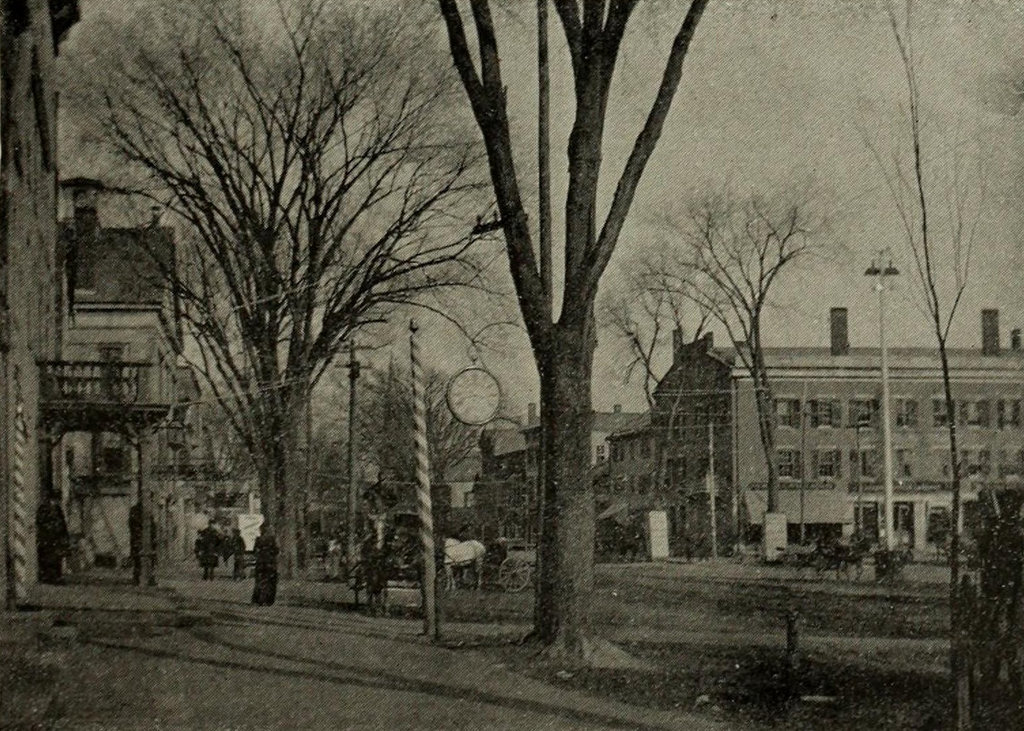

The scene in 2018:

Westfield’s Civil War monument is located here at the southwest corner of Park Square, on a traffic island at the end of Court Street. It was an early work by noted sculptor Melzar Hunt Mosman, a native of Chicopee, Massachusetts. He was a Civil War veteran, and he went on to have a successful career, specializing in Civil War monuments during the late 19th century. This statue here in Westfield was dedicated on May 31, 1871, and it memorialized the 66 Westfield residents who died in the war. The model for the soldier atop the monument was Captain Andrew Campbell of Westfield, with whom Mosman had served in the 46th Regiment during the war.

The keynote speaker at the dedication ceremony was General Hugh Judson Kilpatrick, a Civil War officer from New Jersey who had recently returned from a four-year stint as the U. S. Minister to Chile. In his speech, he praised the bravery and dedication of the soldiers from Massachusetts. He reminded the audience of the righteousness of the Union cause, while also denouncing the treason and atrocities of the Confederacy. In particular, he rebuked former Confederate President Jefferson Davis, declaring him to be “the arch-traitor who long since should have passed from a scaffold to an unhallowed grave.” At this point, the audience interrupted his speech with applause, and after he finished his thoughts on Davis, they responded with “great cheering,” according to the Springfield Republican account of the speech.

Aside from General Kilpatrick, the ceremony also included short speeches from Lieutenant Governor Joseph Tucker and three Civil War officers from Massachusetts: Brigadier General Henry Shaw Briggs of Pittsfield, Brevet Brigadier General William Sever Lincoln of Worcester, and Colonel Joseph B. Parsons of Northampton. Reverend Henry Hopkins, a Civil War chaplain who served as pastor of the Second Congregational Church in Westfield, gave the opening prayer and also read a poem. The ceremony was presided over by District Attorney Edward Bates Gillett, who made brief opening remarks and later introduced Mosman to the crowd after the statue was unveiled.

The first photo was taken about 20 years later, at a time when the Civil War was still within the living memory of many Westfield residents. It shows the view of the statue from the north, and in the background of the photo is the Morgan Block. This brick commercial building was already old by this point, having been constructed around the late 1810s by Major Archippus Morgan. He ran a general store here, while also renting space in the building to other retail tenants. Later in the 19th century, the building briefly served as the first home of the Westfield YMCA, and over the years it was used by a variety of other businesses, eventually becoming commercial offices in the first half of the 20th century.

Today, more than 125 years after the first photo was taken, remarkably little has changed in this scene. The monument has remained a landmark here in downtown Westfield, with few changes aside from the shrubbery at the base and the blue-green patina on the bronze surfaces. The Morgan Block is also still standing in the background. It has seen minor exterior alterations, including the addition of a dormer window on the left side and a bay window on the first floor of the right side, but overall it stands as a rare surviving example of an early 19th century commercial block here in Westfield.