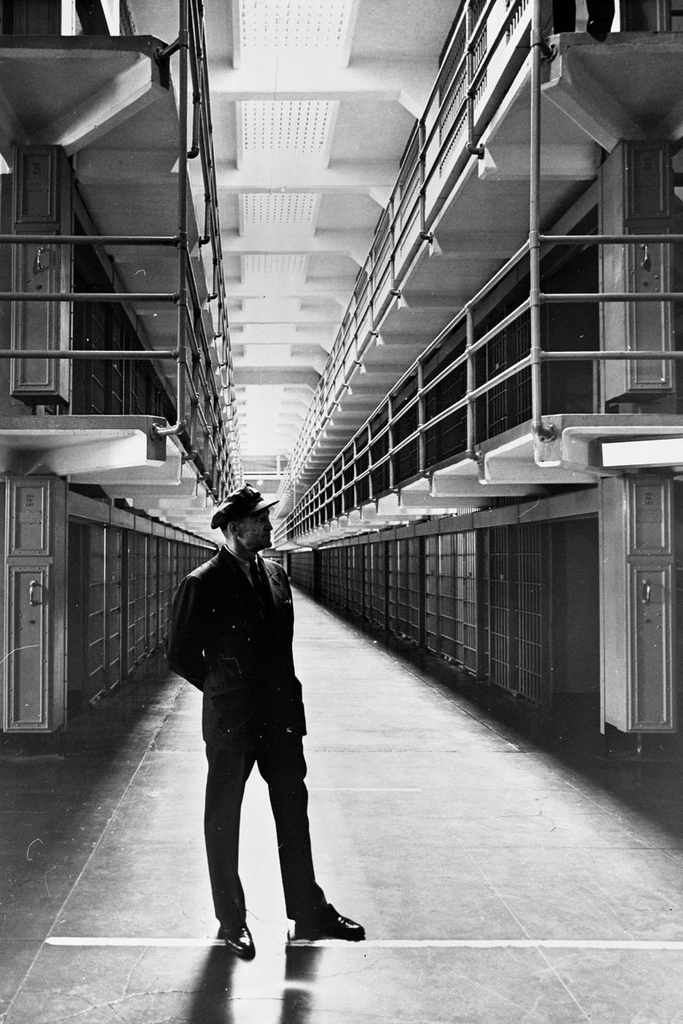

Alcatraz guard Carl T. Perrin, on duty on March 21, 1963, the last day of the prison’s operation. Photo taken by Keith Dennison, courtesy of the National Park Service.

The scene in 2015:

The corridors between the cell blocks at Alcatraz were named after major streets; this particular one was known as Broadway, and it was the central corridor in the facility, separating blocks B and C. The block had three levels of cells, and most of the inmates were kept in either B or C blocks, with the more isolated D block being used for isolation and punishment, like solitary confinement.

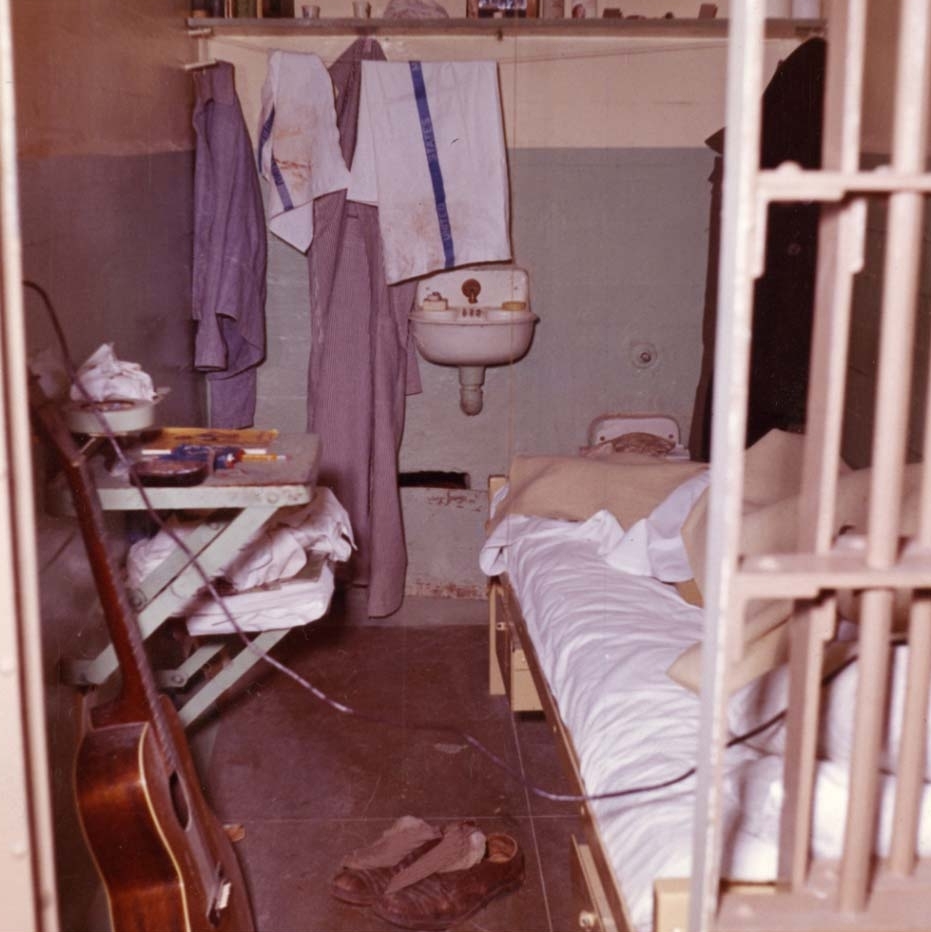

Because Alcatraz was intended for the nation’s most problematic federal prisoners, the prison enforced many strict regulations. Each cell housed only one person, and conversations between inmates were strictly limited to discourage them from coordinating escapes. “Lights out” was at 9:30 P.M., and, unless they worked a prison job, the inmates spent nearly 23 hours a day in their cells, passing the time by reading, smoking, and occasionally playing musical instruments or making artwork. Images of the interior of the cells can be seen in this earlier post and this one.

This post is part of a series of photos that I took in California this past winter. Click here to see the other posts in the “Lost New England Goes West” series.