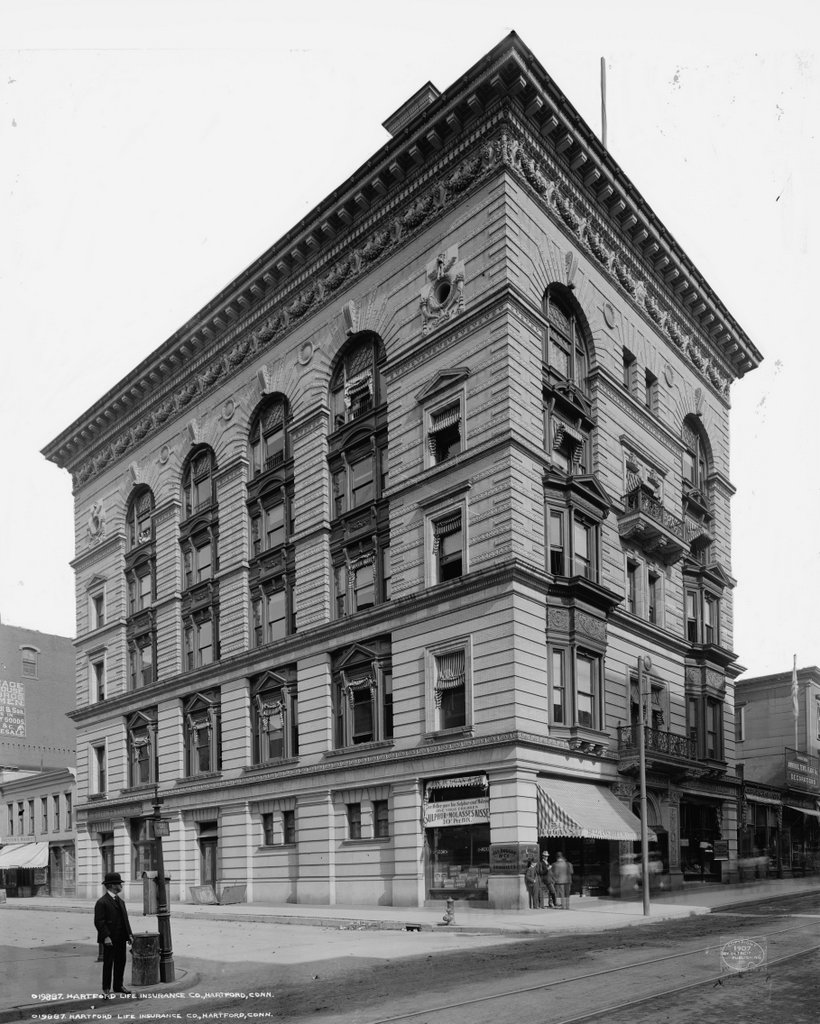

The Connecticut Mutual Life Insurance building at the corner of Main and Pearl Streets in Hartford, around 1907. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The same location in 2015:

These two views were taken near the scene on Main Street in this post; the building on the left in the 1905 photo there is the same one featured here. Connecticut Mutual was founded in 1846, and like many other insurance companies it was headquartered in Hartford. The company built this Second Empire style building here in 1872 and expanded it in 1901, but over the years other alterations removed much of its original architectural value. Connecticut Mutual moved out of downtown in 1925, and the building was drastically altered again, becoming the home of Hartford National Bank and Trust. The building remained here until 1964, when it was demolished to build the present skyscraper. As for its original tenant, Connecticut Mutual, they no longer exist either; in 1995 they merged with MassMutual, and most of the company moved to the MassMutual headquarters in Springfield, Mass. Today, these two photographs offer a comparison of architectural styles – the ornate, eclectic Second Empire building of the 1870s in one scene, and the plain concrete and glass 1960s-era Brutalist architecture of the present-day scene.