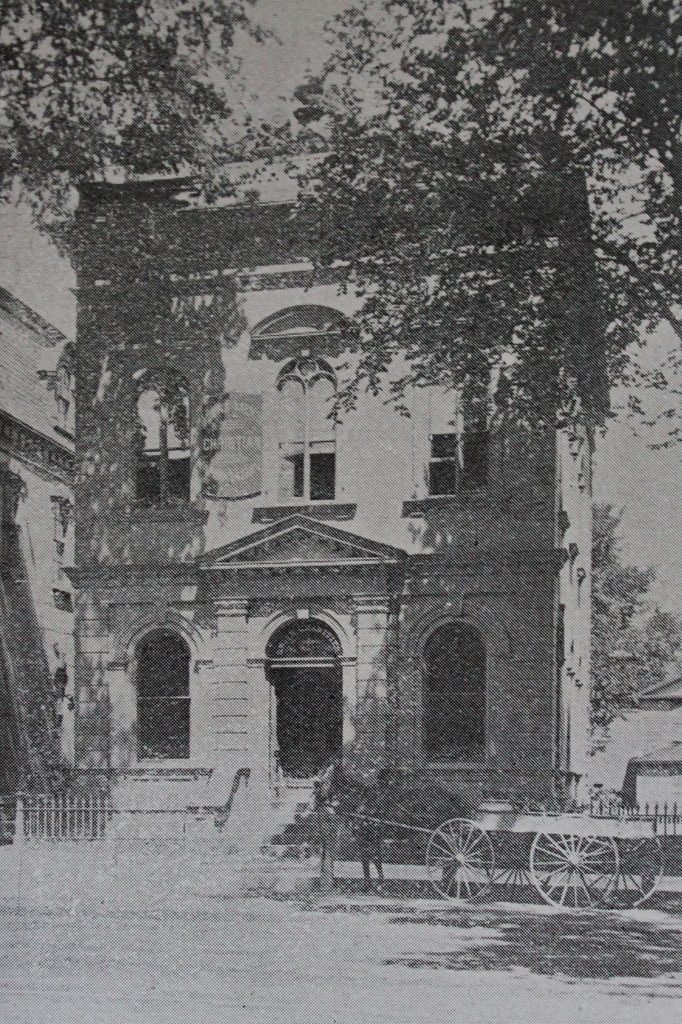

The Universalist Church at the corner of Center and Springfield Streets in Chicopee, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2017:

This Greek Revival-style building was constructed in 1836, and was originally owned by the Mechanics’ Association. However, within a few years it was sold to a Universalist society, which had been founded in 1835 and formally established as a church in 1840. At the time, Chicopee was still part of Springfield, and this neighborhood was known as Cabotville, but in 1848 Chicopee was incorporated as a separate town. The church building occupied a prominent location in the new town center, at the southern end of Market Square, and the Universalists continued to meet here until the society was disbanded in 1883.

By the time the first photo was taken in the early 1890s, the building had become the United Presbyterian Church. However, because of its valuable location in the center of Chicopee, the ground floor was rented to commercial tenants, including Carter & Spaulding’s grocery store, which can be seen on the left side of the first photo. Subsequent early 20th century tenants included the Gaylord-Kendall Company bankers and the Association Co-Operative meats and groceries, and the Presbyterian church remained here until 1925, when the congregation moved to a new church building on Newbury Street.

After this move, the old church building was converted entirely to commercial use. By the mid-20th century the ground floor was home to Paul’s Shoes on the left side and the Peter Pan Café on the right, and the church sanctuary had been converted into the Peter Pan Ballroom. Around this time the exterior was also significantly altered, including the removal of the cupola and the installation of aluminum siding, which hid most of the building’s original architectural features.

Today, more than 125 years after the first photo was taken, the old church building is still standing, although it is hardly recognizable. The exterior is now covered in brick, and only the window arrangement gives any clue that it is still the same building from the first photo. Formerly Bernardino’s Restaurant, the building is now home to the Munich Haus, a German restaurant that opened here in 2004. At the time, the three-story brick Temple Block, seen on the right side side of the first photo, was still standing. It was built in 1876 but was destroyed in a fire in 2011, and the site of the building is now a biergarten for the Munich Haus.