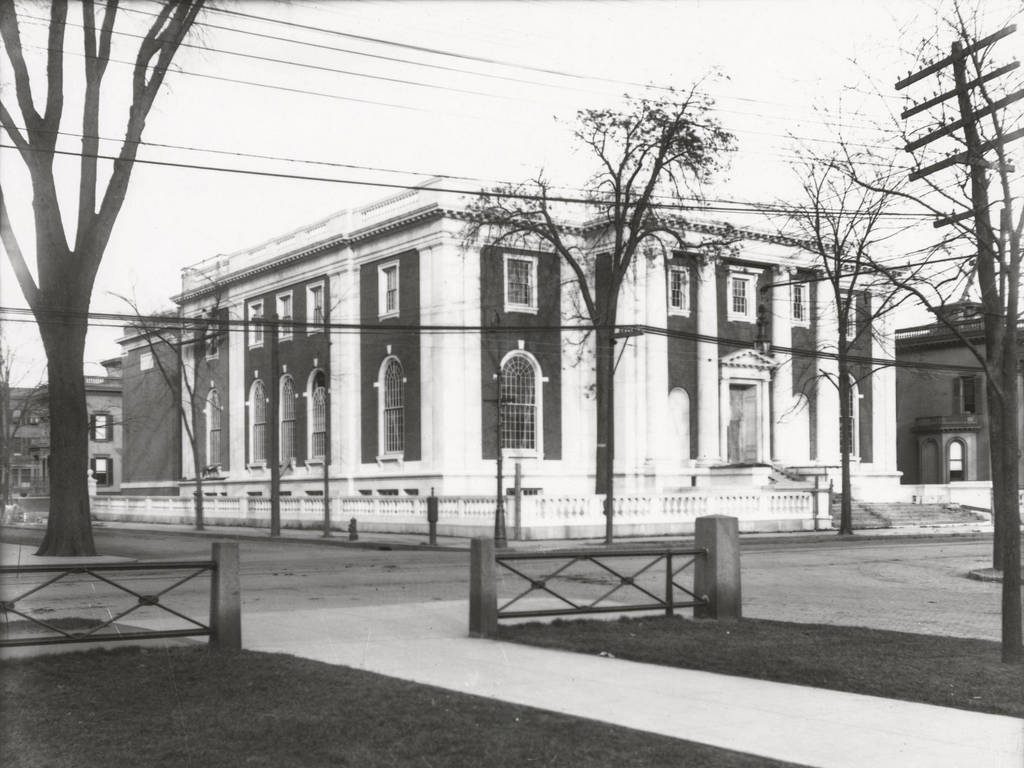

The Tontine Hotel, at the corner of Church and Court Streets in New Haven, around 1900-1907. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

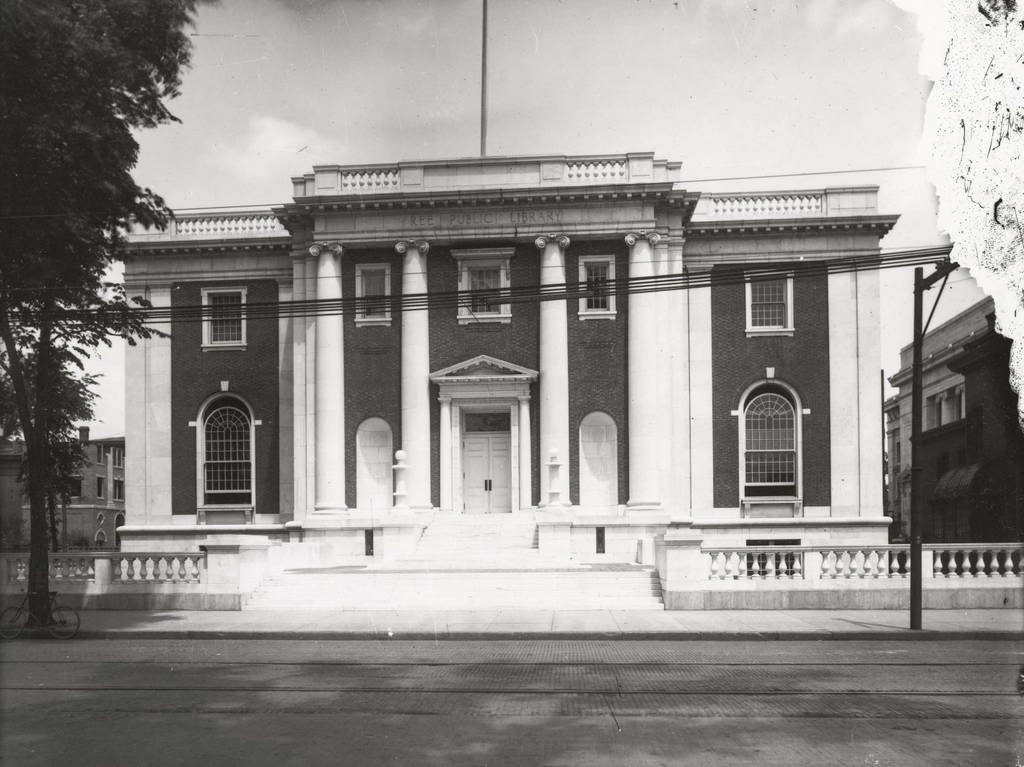

The scene around 1918. Image from A Modern History of New Haven and Eastern New Haven County (1918).

The scene in 2018:

The first photo shows the Tontine Hotel, which had been a New Haven landmark for nearly a century before the photo was taken. It was built sometime in the mid-1820s – sources differ on the exact date – and its design was the work of noted local architect David Hoadley. The Tontine was a prominent hotel in its early years, and its notable visitors during this time included Indian chief and orator Red Jacket, who gave a speech here in 1829, and Daniel Webster, who came here in 1832.

However, perhaps the most significant group of guests came a year later, when President Andrew Jackson came to New Haven in June 1833, accompanied by then-Vice President Martin Van Buren, Secretary of War Lewis Cass, Secretary of the Navy Levi Woodbury, and Governor William L. Marcy of New York. The party arrived in New Haven by steamboat at around 1 p.m. on the afternoon of June 15 and went to the State House, where the president was addressed by the governor and the mayor. Jackson was then escorted through the streets in a procession that took a circuitous route through the city, eventually ending here at the Tontine. Jackson spent the night at the hotel, and in the morning he attended Sunday services at Trinity Church before departing for Hartford.

The Tontine Hotel was still in business when the first photo was taken some 70 years later. At the time, it was known as White’s New Tontine, as its proprietor was George T. White. An advertisement in the 1902 city directory declared it to be “Under New Management. All the Modern Improvements. Refurnished Throughout,” and rooms ranged from $1.00 to $2.00 per night. The first photo also shows a restaurant in the basement of the hotel. The signs indicate that it was a buffet that offered “White’s steaks, chops and game in season,” and the directory described it as a “cafe, restaurant, and rathskeller” that was open from 6 a.m. until midnight. In addition to this restaurant, there are several other amenities visible in the first photo, including a barber shop and a “boot blacking emporium” that were both located on the left side of the building.

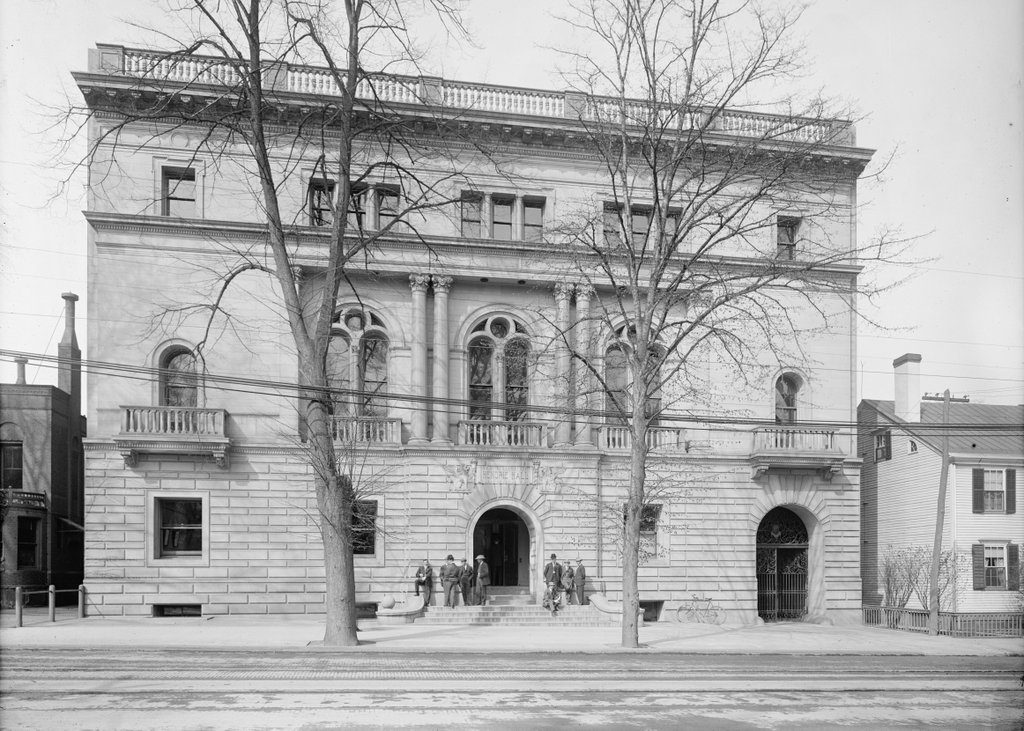

Despite its historic significance, though, the site of the Tontine Hotel was eyed for redevelopment soon after this photo was taken. It was demolished by around 1913, in order to make way for a new federal courthouse and post office. Unlike the fairly modest brick hotel, the new courthouse was an imposing marble structure. It had a Classical Revival design, including a large front portico with ten Corinthian columns, and it was the work of noted architect James Gamble Rogers. The cornerstone was laid in 1914, in a ceremony that featured a speech by former president and future chief justice William Howard Taft, but the building was not completed until 1919, a year after the second photo was taken.

Like the architecturally-similar New Haven County Courthouse, which stands nearby at the northeastern corner of the Green, the federal courthouse was threatened with demolition in the mid-20th century. However, like the county courthouse, it was ultimately preserved, and it underwent a major renovation in the 1980s. The post office moved out in 1979, but otherwise the building remains in use, as one of thee federal courthouses in the District of Connecticut. In 1998, it was renamed the Richard C. Lee United States Courthouse, in honor of the longtime mayor of New Haven who helped to preserve the building, and in 2015 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.