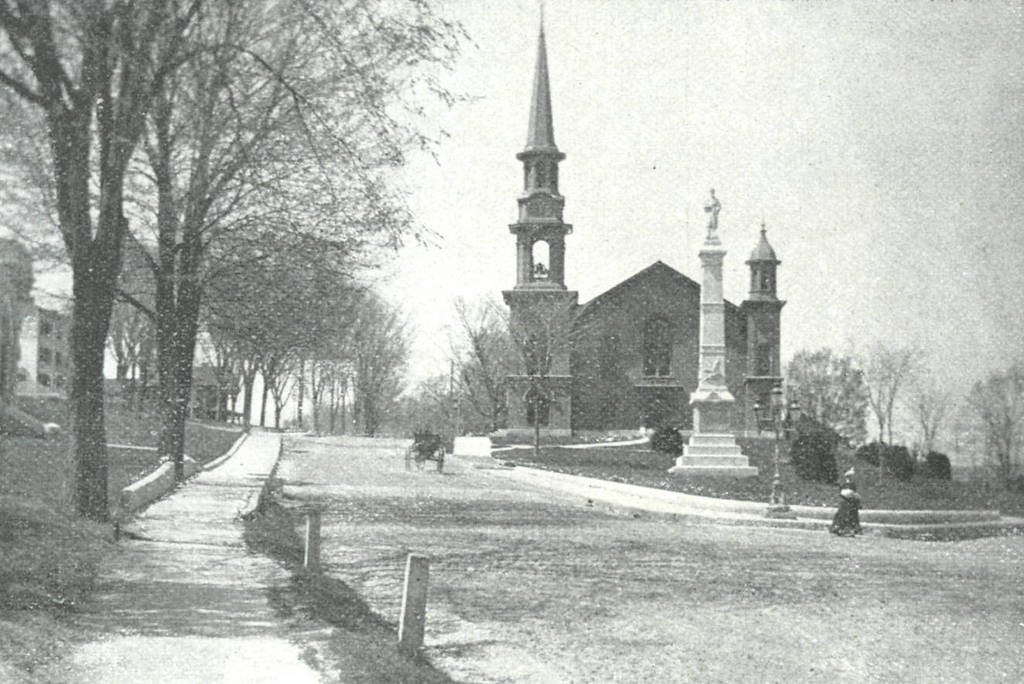

Looking across the Potomac River towards Harpers Ferry from the Maryland side of the river, around June 14, 1861. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Civil War Collection.

The same view in 2015:

The town of Harpers Ferry had only about 1,300 residents at the start of the Civil War, and its land area was just a half a square mile, but it became among the most contested places of the war. It was literally located on the border of the Union and the Confederacy, changing hands eight times during the war and ending up in a different state by the time it was over.

As its name implies, this area was first settled as a ferry crossing. Originally part of Virginia, it is located at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers, and beginning in 1733 colonist Peter Stevens operated a ferry across the Potomac here, enabling settlers from Maryland and Pennsylvania to access the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. The town isn’t named Stevens Ferry, though, because around 1748 he sold his land and ferry to Robert Harper, who operated it until his death in 1782.

Because of its transportation connections and relatively defensible position, Harpers Ferry was one of two locations, along with Springfield, Massachusetts, selected by George Washington for federal armories. Further transportation developments came in the 1830s: the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal (seen in the lower foreground of both photos) was completed as far as Harpers Ferry in 1833, several stagecoach lines were opened in 1834, and the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad reached the Maryland (foreground) side of the river later in 1834. The first railroad bridge was completed in 1837, allowing a direct connection from the armory to the rapidly growing national rail network.

By 1850, this small town had grown to over 1,700 people thanks to the armory (visible along the waterfront to the right in the first photo), but before the end of the decade it would become the center of one of the major precursors to the Civil War. In October 1859, abolitionist John Brown led a raiding party of 22 men in an attempt to capture the arsenal and start a slave rebellion. The raid ultimately failed, and most of the raiders were either killed or were captured and executed, including John Brown, whose December 2 execution was seen as a martyrdom by many northern abolitionists.

The Civil War began just a year and a half after the raid, and Virginia’s state legislators voted to secede on April 17, 1861. One of the state’s first objectives was to take the Harpers Ferry arsenal, which at the time was guarded by just 65 men. Led by Lieutenant Roger Jones, they destroyed the arsenal and its 15,000 guns before evacuating the town ahead of the Confederates. The Confederates didn’t occupy the town for long, though. They left on June 14, and burned the Baltimore & Ohio bridge as they left. The remains of the bridge can be seen in the foreground of the first photo, which according to the caption was “photographed immediately after its evacuation by the rebels.”

When the first photo was taken, the town was still relatively intact, but as the war progressed it became somewhat of a no man’s land. Despite the loss of the armory, it was still a vital transportation corridor for armies on both sides, so between 1861 and 1863 it changed hands several more times. West Virginia became a state on June 20, 1863, with Harpers Ferry citizens voting 196 to 1 to leave Virginia and join the union. The town was briefly occupied by the Confederates in early July, but they soon evacuated for the last time and Union solders returned on July 13, finally bringing stability to Harpers Ferry for the rest of the war.

In terms of population, Harpers Ferry never fully recovered from the Civil War. The armory never reopened, and the population has steadily fallen to less than 300 as of the 2015 census. However, it has become a major tourist destination, with the Harpers Ferry National Historic Park now comprising much of the historic town. Although the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal has not operated in nearly a century, there are still several railroad lines that pass through here.

One of the bridges, seen to the right in the 2015 photo, also carries the Appalachian Trail over the Potomac River on a pedestrian walkway on the left side of the bridge. The bridge pier in the foreground is from an earlier railroad bridge that had been built on the spot of the one that was destroyed in 1861. This bridge, in turn, was washed away in a 1936 flood, and it was never rebuilt. Today, the modern railroad bridge, as well as trees along the river, help to hide the view of Harpers Ferry, with only a few buildings visible in the 2015 scene.

(Much of the information for this post came from “To Preserve the Evidences of a Noble Past”: An Administrative History of Harpers Ferry National Historical Park (2004). For further reading, it and other resources are available online here at the National Park Service website.)