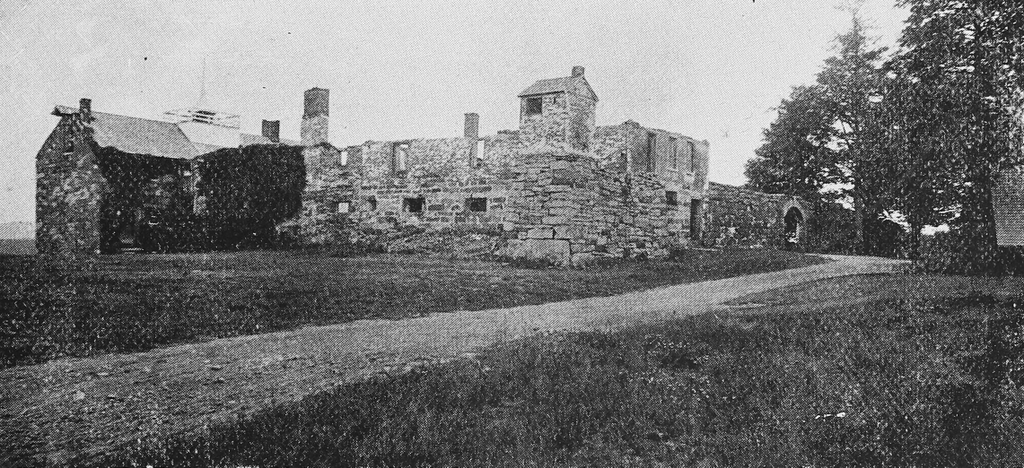

The Old Newgate Prison on Newgate Road in East Granby, around 1895. Image from The Connecticut Quarterly (1895).

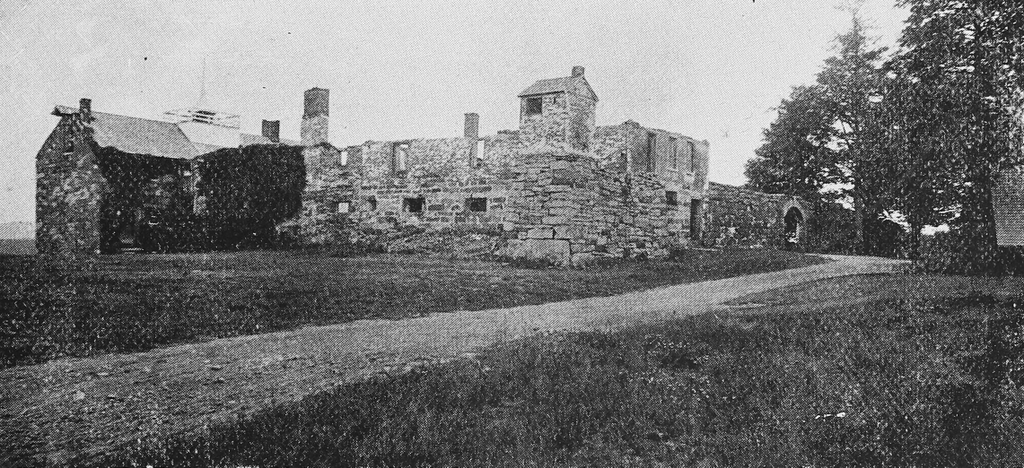

The scene in 2018:

By the time the first photo was taken in the mid-1890s, the Old Newgate Prison was already recognized as an important historic landmark. Its history dates back to 1705, when copper was discovered here on the western slope of the Metacomet Ridge. A copper mine was opened here two years later, and it is generally considered to be the first copper mine in the American colonies. It was active throughout the first half of the 18th century, creating a network of tunnels that branched out from a vertical shaft.

The mine was largely abandoned for the next few decades, but in 1773 the underground tunnels were repurposed as a prison. The first warden was John Viets, who kept a tavern across the street from the mine. He provided food and other supplies for the prisoners, while also continuing to operate his tavern, which was known to occasionally cater to the needs of the wealthier prisoners. In 1774, the prison’s first full year of operation, Viets was paid 29 pounds, 5 shillings, and 10 pence for his services, and the following year he received nearly 150 pounds, although these amounts evidently include both his salary and his reimbursement for expenses.

The job of prison warden certainly came with its risks, and the 1892 book Newgate of Connecticut: Its Origin and Early History, by Richard H. Phelps, relates one such incident involving Viets:

At that time no guard was kept through the day, but two or three sentinels kept watch during the night. There was an anteroom or passage, through which to pass before reaching their cell, and the usual practice of Capt. Viets, when he carried their food, was, to look through the gates into this passage, to observe whether they were near the door, and if not, to enter, lock the door after him, and pass on to the next. The inmates soon learned his custom, and accordingly prepared themselves for an escape. When the captain came next time, some of them had contrived to unbar their cell door, and huddled themselves in a corner behind the door in the passage, where they could not easily be seen, and upon his opening it, they sprang upon him, knocked him down, pulled him in, and made good their escape.

Most of these prisoners were eventually recaptured, but this was just one of many such escapes from the old copper mine, which proved less secure than the colonial government had anticipated. In fact, the first recorded prisoner here, convicted burglar John Hinson, escaped after just 18 days, supposedly after a female acquaintance pulled him up via the mine shaft. This was followed by at least four escapes in April 1774, including one convict who escaped just four days into his sentence.

Prisoners here often took drastic measures in their attempts to escape. In 1776, a group of prisoners in the tunnel attempted to set fire to the blockhouse, which was situated at the top of the mine shaft. They succeeded in lighting a fire, but it filled the tunnels with smoke, killing one of the men and nearly suffocating the rest of them. The blockhouse was subsequently rebuilt, but it was soon burned again by the prisoners.

Probably the most dramatic escape from Newgate came in the closing years of the American Revolution, when the facility held a number of Loyalist prisoners. By this point, the prison had significantly increased security, including the addition of a fence and an increase in the number of guards. However, this did not stop a group of about 30 prisoners, mostly Loyalists, from taking control of the prison and escaping, as described by Phelps in Newgate of Connecticut:

On the night of the 18th of May, 1781, the dreadful tragedy occurred which resulted in the escape of all the prisoners. A prisoner was confined, by the name of Young, and his wife wishing to be admitted into the cavern with him, she was searched, and while two officers were in the act of raising the hatch to let her down, the prisoners rushed out, knocked down the two officers, and seizing the muskets of nearly all the rest who were asleep, immediately took possession of the works, and thrust most of the guards into the dungeon, after a violent contest. One of them, Mr. Gad Sheldon, was mortally wounded, fighting at his post, and six more wounded severely.

Some of the prisoners were wounded, but most were able to escape, although many were subsequently recaptured. Newgate continued to be used to imprison Loyalists after this incident, but in 1782 the prison was burned again, enabling the inmates to escape. This was, as Phelps noted, “the third time the prison buildings had been burned in nine years, since its first inauguration, and more than one-half of the whole number of convicts had escaped by various means.”

Newgate became a state prison in 1790, and officials soon set out to improve the facility. That same year, a wooden fence was constructed, creating a prison yard of about a half acre, and a number of new buildings were constructed. Prisoners generally slept in the tunnels, but they came to the surface during the daytime to perform work. The original intention had been to make the prisoners mine for copper, but officials quickly realized that their mining tools could also be used to aid in escaping, so this plan was scrapped. Instead, many prisoners made nails, while others were assigned to walk on the treadmill, a human-powered wheel that ground grain.

In Newgate of Connecticut, Phelps provides the following description of daily life here in the prison:

The hatches were opened and the prisoners called out of their dungeon each morning at daylight, and three were ordered to “heave up” at a time; a guard followed the three to their shops, placing them at their work, and chaining those to the block whose tempers were thought to require it. All were brought out likewise in squads of three, and each followed by a guard. . . .

After a while their rations for the day were carried to them in their several shops. They consisted for each day of one pound of beef or three-fourths of a pound of pork, one pound of bread, one bushel of potatoes for each fifty rations, and one pint of cider to every man. Each one divided his own rations to suit himself – some cooked over their own mess in a small kettle at their leisure, while others disregarding ceremonies, seized their allowance and ate it on an anvil or block. They were allowed to swap rations, exchange commodities, barter, buy, and sell, at their pleasure. Some would swap their rations for cider, and often would get so tipsy that they could not work, and would “reel too and fro like a drunken man.” . . .

All were allowed to work for themselves or others after their daily tasks were finished, and in that way some of them actually laid up considerable sums of money. A little cash, or some choice bits of food from people in the neighborhood, procured many a nice article of cabinet ware, a good basket, a gun repaired by the males, or a knit pair of stockings by the female convicts. . . .

The punishments inflicted for offenses and neglect of duty were severe flogging, confinement in the stocks in the dungeon, being fed on bread and water during the time, double or treble sets of irons, hanging by the heels, &c., all tending to inflame their revenge and hatred, and seldom were appeals made to their reason or better feelings. Most of them were placed together in the night; solitary lodging, as practiced at this day, being regarded as a punishment, rather than a blessing to them.

By the early 19th century, there were a number of new above-ground structures here at Newgate. The current stone fence was built in 1802, replacing the earlier wooden one, and during this period a new brick guardhouse was constructed atop the mine shaft. The nail shop was located on the north side of the yard, and the south side eventually had three buildings along the inside of the wall. In the southeast corner, closest to the foreground in this scene, was the chapel, which was built around 1815. Just to the west of it was a two-story building that housed a cooper shop, hospital, kitchen, and shoemaker’s shop. Furthest to the west, on the far left side of the scene, was a large four-story building that was constructed in 1824. It had several different purposes, with space for the treadmill, rooms for guards, and cells for 50 prisoners.

With the completion of this new building, the prisoners were able to be moved above ground, and the mine tunnels were no longer used on a regular basis. However, Newgate still faced issues of overcrowding and poor conditions for its inmates, and it became a target for prison reformers, who advocated the opening of a new, more humane prison in Connecticut. Throughout the early 19th century, Newgate also continued to have problems with escape attempts and riots, despite the many improvements here since the colonial period.

As a result, a new state prison was constructed in Wethersfield, and the old prison here in Granby – now located within the town of East Granby – was closed for good in 1827. However, in a fitting conclusion to its time as a prison, this facility saw one last escape attempt, which occurred on the last night before the prisoners were transferred to Wethersfield. On that night, a convicted counterfeiter named Abel N. Starkey asked to sleep in the old tunnels. The guards permitted this, and during the night Starkey attempted to escape by climbing up the rope of the well shaft. As he was ascending the shaft, though, the rope broke, and he was killed when he fell back down to the bottom.

After the prison closed, there were several efforts to revive the site as a copper mine, but with little success. For a time, the guardhouse was used as a private residence, with the owner often giving tours to curious visitors. By the late 19th century, much of the prison was in ruins, as shown by the crumbling walls in the first photo, but it had already become a local landmark and a popular tourist destination.

The prison would deteriorate even further in 1904, when a fire destroyed the 1824 cell block building on the left side of the scene. However, the rest of the property continued to be used for a variety of purposes during the first half of the 20th century. The guardhouse served as a dance hall during the 1920s and 1930s, and the grounds were occasionally used for public events and exhibitions.

The state of Connecticut acquired the property in 1968 and converted it into a museum. This included stabilizing the ruins, and digging a new entrance tunnel with stairs, which made it easier and safer for visitors to descend into the old mine. In 1972, the site was designated as a National Historic Landmark, in recognition of its historical significance as one of the first copper mines and one of the first state prisons in the country.

Because of structural problems, Old Newgate Prison was closed to the public in 2009, beginning a nearly decade-long project to stabilize the ruins. However, it reopened in 2018, and visitors can once again tour the remains of the above-ground buildings, and descend into the old tunnels. Following the 1904 fire that destroyed the cell block building, the old guardhouse is the only building here that survives intact, and its roof and chimney are visible beyond the walls in the 2018 photo. Otherwise, though, there have not been many changes in this scene, and the exterior of the prison still looks much the same as it did during the late 19th century.