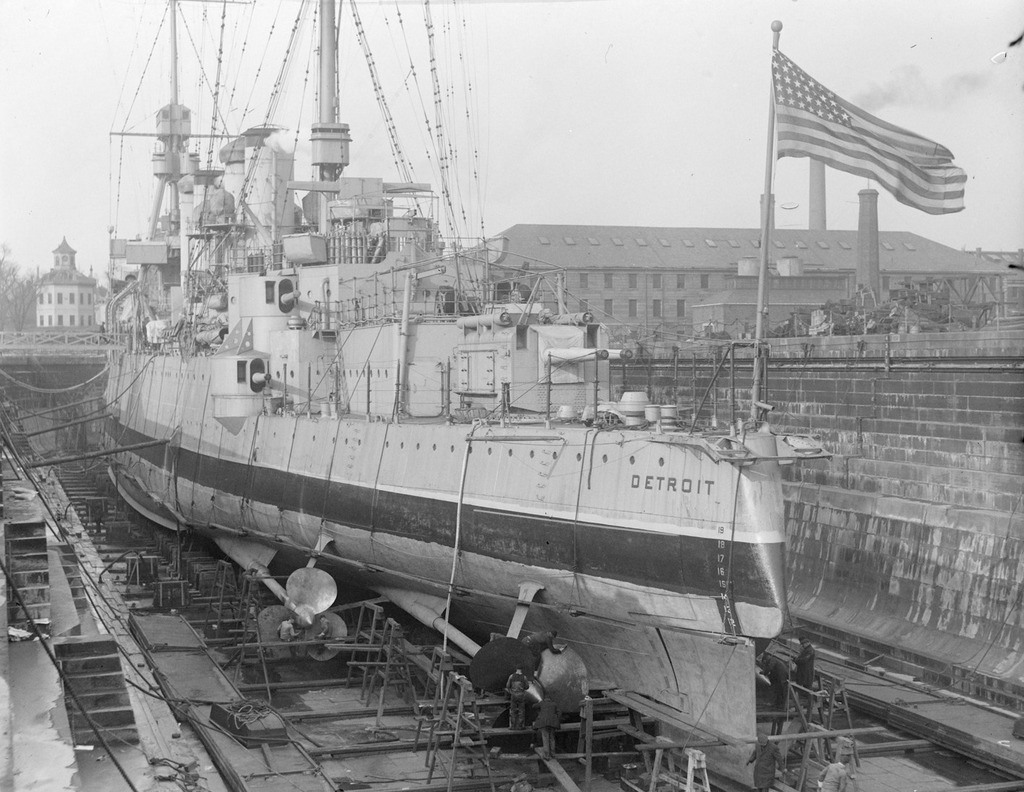

The cruiser USS Detroit in Dry Dock 2 at Boston Navy Yard, on December 16, 1928. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library, Leslie Jones Collection.

The scene in 2015:

Taken about 23 years after the photo in the previous post, this view of Dry Dock 2 shows the USS Detroit (CL-8), an Omaha-class light cruiser, undergoing work at the Boston Navy Yard. The Detroit had been built in nearby Quincy, Massachusetts, and was commissioned in 1923. Several years after the first photo was taken, she was transferred to the Pacific, and was based out of San Diego before being moved to Pearl Harbor in 1941. She was present during the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, and survived the battle without any damage, and went on to see extensive service in World War II, including being present in Tokyo Bay for the surrender in 1945. Following the war, though, the Detroit was sold for scrap in 1946, along with many other obsolete surplus ships.

The Boston Navy Yard, as mentioned in the previous post, closed in 1974, and part of it was taken over by the National Park Service. Today, many of the historic buildings and other structures have been preserved, including Dry Dock 2 and some of the buildings in the distance. One of the most distinctive buildings in the yard is the octagonal Muster House, which can be seen just to the left of the ship. It was built in the 1850s, and it is still standing today, partially hidden by trees in the distance. The long building in the center of the photo has also been preserved and repurposed; it is now the MGH Institute of Health Professions.