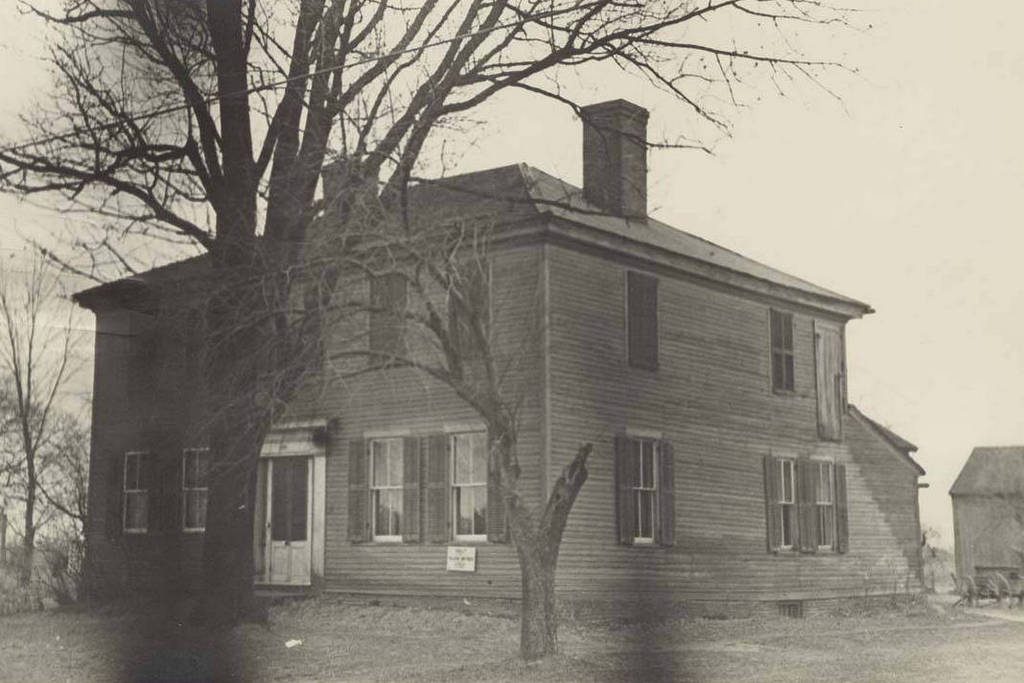

The house at 29 Ingersoll Grove in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2017:

The life of Lyman Besse was a classic Gilded Age rags-to-riches story, beginning with his birth in Wareham, Massachusetts in 1854. His father was a farmer, and died when Lyman was just 11, and five years later he left school and traveled to West Virginia, where he found work as a clerk in a general store. By the time he turned 18, he was back in Massachusetts, earning six dollars a week while working for a clothing merchant in Taunton. In 1876, he came to western Massachusetts to work for C. B. Harris & Company, but the following year, at the age of 23, he decided to go into business for himself.

Working with business partner J. E. Foster, he opened his first clothing store in Bridgeport, Connecticut in 1877. The business was a quick success, and he soon began opening stores in other cities across the northeast. In 1879, he married his childhood friend, Henrietta Segee, and they lived in Bridgeport for the next nine years. However, as his business empire expanded, he decided to move to Springfield, which had a more central location. In 1888, he and his family moved into this newly-built house on Ingersoll Grove, in one of the most desirable locations in the McKnight neighborhood.

Like most of the other houses in the neighborhood, Besse’s mansion had Queen Anne-style architecture, although this has been somewhat altered over the years. The property also included a massive carriage house in the backyard, and a driveway that connected to both Ingersoll Grove as well as Clarendon Street behind the carriage house. The grounds were well-landscaped, and beyond the backyard was the McKnight Glen, a section of undeveloped parkland owned by the city. As described in an 1893 volume of The National Magazine, “Mr. Besse’s home is situated in the most picturesque section of the delightful and healthful ‘Highland’ region of Springfield, and is one of the most pleasant and attractive homes in the city.”

When the Besse family moved into the house, Lyman was just 34 years old, but he had already achieved considerable success in his clothing business. His company became known as the Besse System, and would ultimately include nearly 50 stores across the eastern United States. In the process, he helped to pioneer the idea of a chain retailer. The same article in The National Magazine declared that he had the largest clothing business in the world, and noted that his ability to buy in such large quantities from his suppliers gave him a considerable advantage over smaller competitors.

Lyman and Henrietta raised six children in this house, and they also regularly employed at least two servants who lived here with the family. After Henrietta’s death in 1926, their daughter Florence moved back to the house to care for her father. Florence was recently divorced from her husband, and she lived here with her two children, Mary Brewster and Kingman Brewster, Jr. Lyman died in 1930, and Florence and the children moved out soon afterward. Kingman, Jr., who was 11 when they left, would go on to gain prominence as the President of Yale University from 1963 to 1977, and then served as the United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom during the Carter administration, from 1977 to 1981.

At some point in the early 20th century, the house lost much of its original Queen Anne appearance. The exterior was covered in stucco, and the open wooden porches were rebuilt with granite and enclosed. The chimneys were also rebuilt of granite, and the front facade gained some symmetry when a dormer window on the left was converted into a gable, matching the original gable on he right side of the house. Otherwise, though, the basic structure of the house remained the same, and both the porte-cochere on the right and the carriage house in the distance have survived. In addition, the interior, with nearly 10,000 square feet of living space, has retained much of its 19th century appearance.

In the early 1930s, the house was sold to James D. Gill, a retired art dealer and bookseller who, among other things, had published King’s Handbook of Springfield in 1884. His wife, Emily Frances Abbey Gill, was a prominent philanthropist who, among other things, gave significant contributions to Springfield College to build a women’s dormitory, which is the current Abbey-Appleton Hall. James was already in his 80s when he moved into the house, and he died only a few years later in 1937. Emily was still living here when the first photo was taken, and she remained here until her death in 1950 at the age of 94.

Since Emily’s death, the house has been variously used as a dress shop and as a nursing home, but it is now a single-family residence again. Like many of the other mansions in the neighborhood, the home has been well-preserved. Although the exterior has changed since it was first built in 1887, there is virtually no difference in its appearance from the first photo, and it is an important contributing property in the McKnight Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.