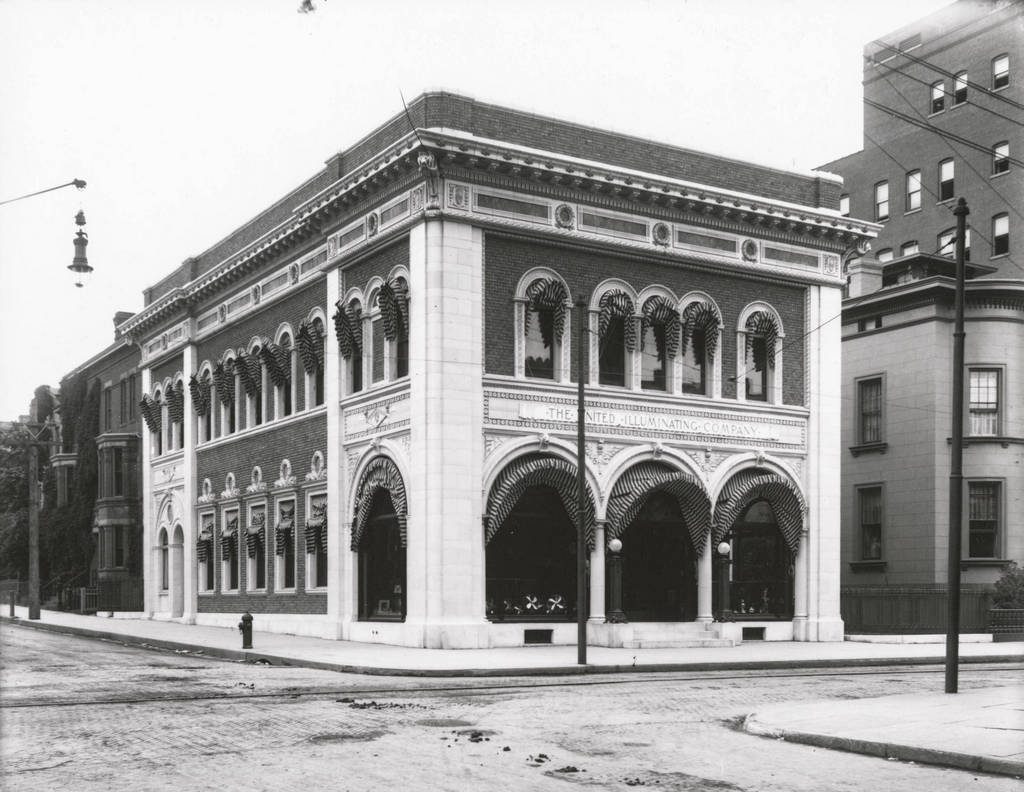

Alumni Hall on the campus of Yale University in New Haven, around 1901. Image taken by William Henry Jackson, courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

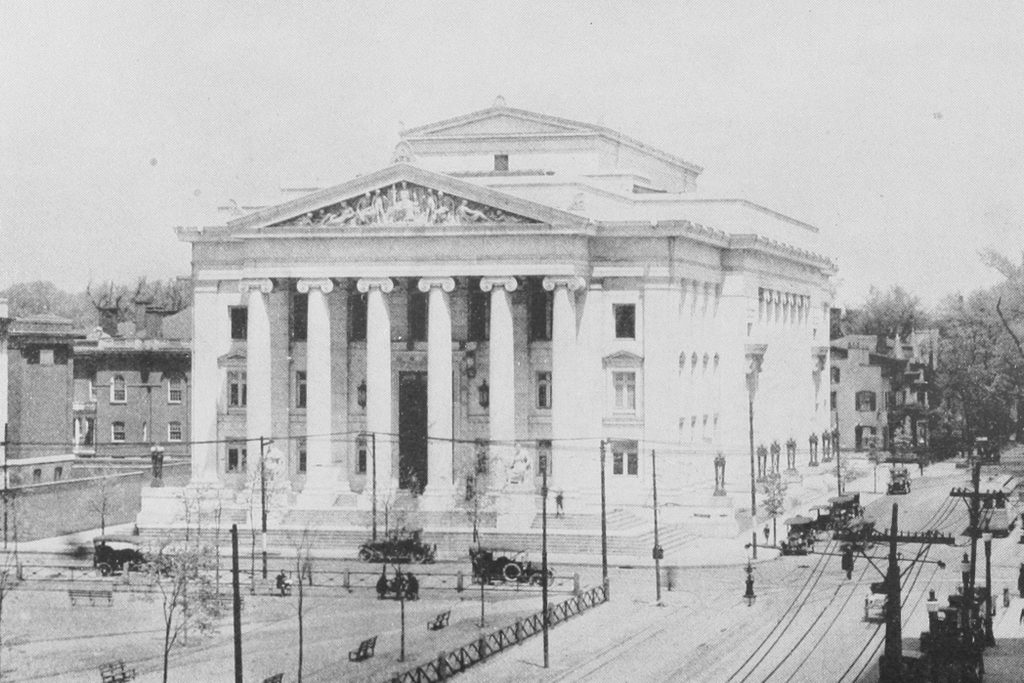

The scene in 2018:

Alumni Hall was completed in 1853, at the northwest corner of Yale’s Old Campus. Its was designed by noted architect Alexander Jackson Davis, and its exterior featured Gothic Revival architecture that was similar to the nearby library building, which was completed a few years earlier. On the interior, the building had just a single large room on the first floor. It measured 98 feet long and 46 feet wide, with a 24-foot-high ceiling, providing ample open space for a variety of functions, including alumni meetings. It was also the site of the school’s entrance examinations, along with the biennial examinations that every student had to take at the end of his sophomore and senior years.

Lyman Hotchkiss Bagg, an 1869 Yale graduate, provides a lengthy account of these entrance exams in his 1871 book, Four Years at Yale, including the following description:

At nine o’clock of a summer’s morning, the “candidate for admission to Yale College” presents himself, with fear and trembling, at the door of Alumni Hall. Just within the entrance, he finds a long table behind which two or three officials are seated, and here he hands in his name and “character.” The envelope containing the latter – which is simply a recommendation of his general morality, signed by the principal of his preparatory school, a clergyman, or other responsible person – is laid aside for future examination, and the candidate is forthwith escorted to his seat. This is at a small octagonal table, the counterparts of which, to the number of a hundred or more, are grouped, in rows of four, at convenient intervals throughout the hall.

Further in his account, Bagg explains how only a few candidates finished on the first day. The rest worked until around 6:30 or 7:00, and then returned to Alumni Hall at 8:00 the following morning in order to finish working. Upon completion, students would receive their results. Some would receive a white piece of paper, which indicated that he was accepted into the school, while others would receive a blue paper, which offered only a conditional acceptance. These latter students would then need to retake certain portions of the exam before he could be be admitted into the freshman class.

While the first floor of Alumni Hall had just a single open room, the upper floor was divided into three different rooms. These were originally intended for use by the school’s three major literary and debating societies: the Linonian Society, the Brothers in Unity, and the Calliopean Society. Each contributed toward the $27,000 construction costs of the building, and upon completion the Linonian Society moved into one of the rooms, and the Brothers of the Unity into another. In between these was a third room, which had originally been intended for the Calliopean Society. However, this organization, which had already been struggling to survive, ended up dissolving before the building was completed, and its share of the construction costs was ultimately returned to its donors.

The other two societies remained active throughout the 1850s and 1860s, but they dissolved in 1870, and their sizable libraries were donated to Yale. The college also took over their former meeting spaces, and the three large rooms were subdivided into recitation rooms. By the time the first photo was taken around 1901, Alumni Hall was not yet 50 years old, but it was already one of the oldest buildings at Yale, following the large-scale campus redevelopments of the late 19th century. Nearly all of the old buildings were demolished in order to construct a quadrangle surrounded by new dormitories, which included Durfee Hall on the far right side of the scene. Alumni Hall survived longer than most, but it was was ultimately demolished in 1911 in order to make room for Wright Hall, the dormitory that now stands on the site.

Unlike the nearby Connecticut Hall, whose threatened demolition a decade earlier had provoked a significant outcry, there was little call for the preservation of Alumni Hall. Some of this may have been due to changing architectural tastes, as this style had largely fallen out of favor by the early 20th century. It also may have been due to the building’s long association with grueling exams, as discussed by Clarence Deming in his 1915 book Yale Yesterday. Reflecting on the building’s demolition, Deming wrote about the impression that it made on students:

And as the same mediæval stronghold had its identity with dungeon, rack and thumbscrew, the undergraduate, less in love with the Hall, could readily span the void of fancy and fir the academic castle to the mental tortures of examination – especially the hated and dreaded “biennials,” covering two full years of the curriculum of the time and on which so many an undergraduate bark went to wreck.

Several pages later, he continued on this medieval theme by writing:

. . . [F]ifty years ago, and for three decades after that, each class, for the awful biennials or not much less awesome annuals, was hived in Alumni Hall under conditions of scrutiny which, if reports of the graduate greybeards are true, rivalled the watch and ward of the cardinals at a papal election. It used to be a tradition, probably untrue, that the octagonal tables, originally square, were sawed off as to their corners and octagonized so that the corners might not cover the hidden “crib.” However that may be, it is certain that the examination agonies and glooms of those college times centered in the Hall where the portraits of the college benefactors looking down from the walls seemed redolent of the Spanish Inquisition and Torquemada. With its dull-hued panellings and massive effects, the Hall has indeed offered little æsthetic and visual relief to the chief of its solemn functions.

Today, the only surviving remnants from Alumni Hall are the two towers, which were salvaged when the building was demolished. They were incorporated into Weir Hall, which is located a block away from here at Jonathan Edwards College, and they are partially visible on the right side of the 2018 photo in this earlier post. Otherwise, the only remaining feature from the first photo is Durfee Hall on the right side. It is now used as a freshman dormitory, as is Wright Hall in the center of the present-day scene. It was completed in 1912, a year after Alumni Hall was demolished, and it was renamed Lanman-Wright Hall in 1993, following a renovation of the building.