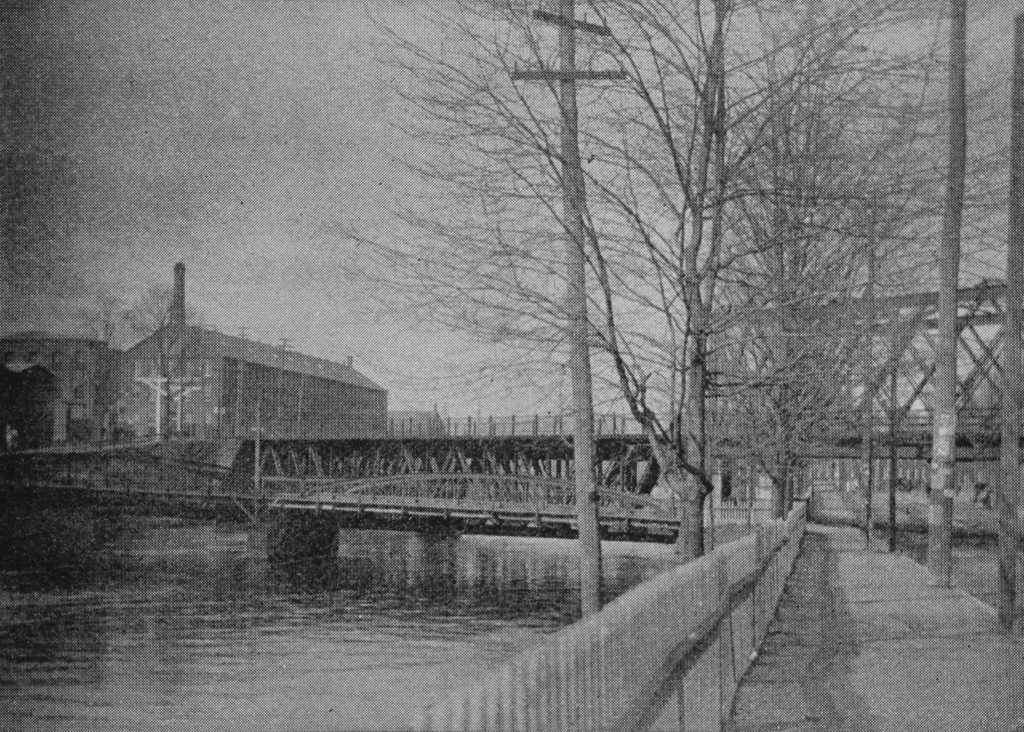

The Old North Bridge over the Concord River, with the memorial obelisk in the foreground, around 1906. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

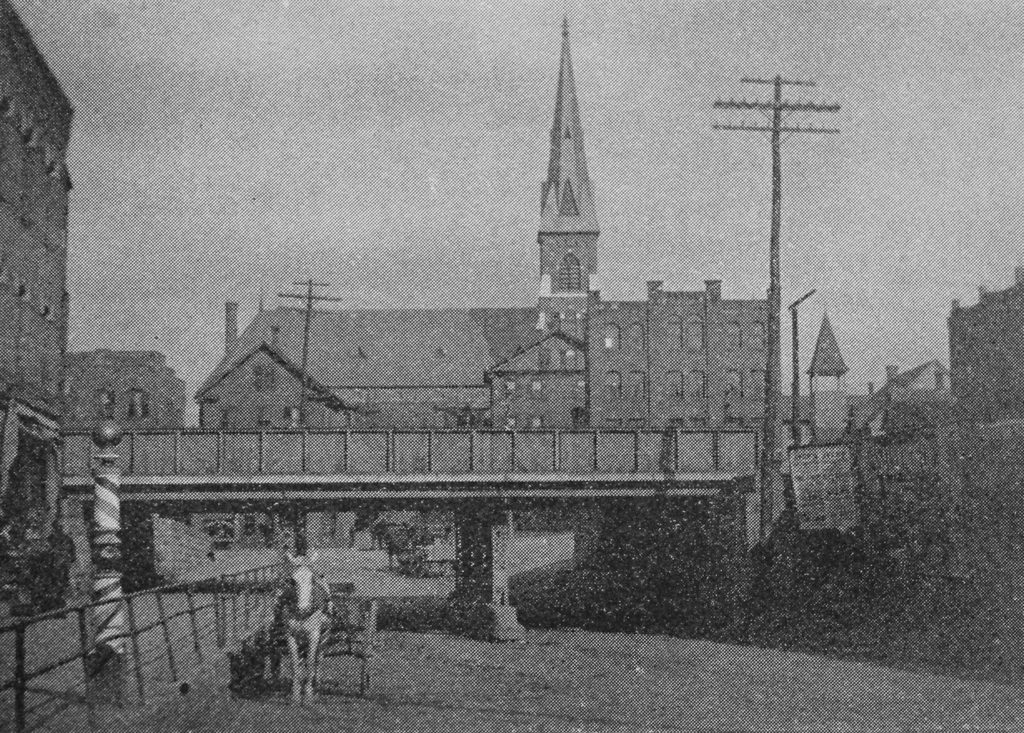

The scene in 2018:

This view shows the scene looking west across the Concord River, at the site of the Battle of Concord, which occurred on April 19, 1775. Along with a brief skirmish in Lexington earlier on the same day, this battle marked the beginning of the American Revolution, and the site is now marked by several monuments and a replica of the original Old North Bridge that stood here at the time of the battle.

The battle was the result of a British attempt to seize colonial munitions that were stored in Concord. Late on the previous night, a force of some 700 British soldiers under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Francis Smith had left Boston, bound for Concord. This prompted Paul Revere and several other messengers to make their famous midnight ride, warning the minutemen in the surrounding towns. By dawn, the British had reached Lexington, where a group of minutemen had assembled on the Lexington Green. The two sides exchanged fire, the first shots of the war, and the result was eight colonists dead and ten wounded, compared to one British soldier who received a minor wound.

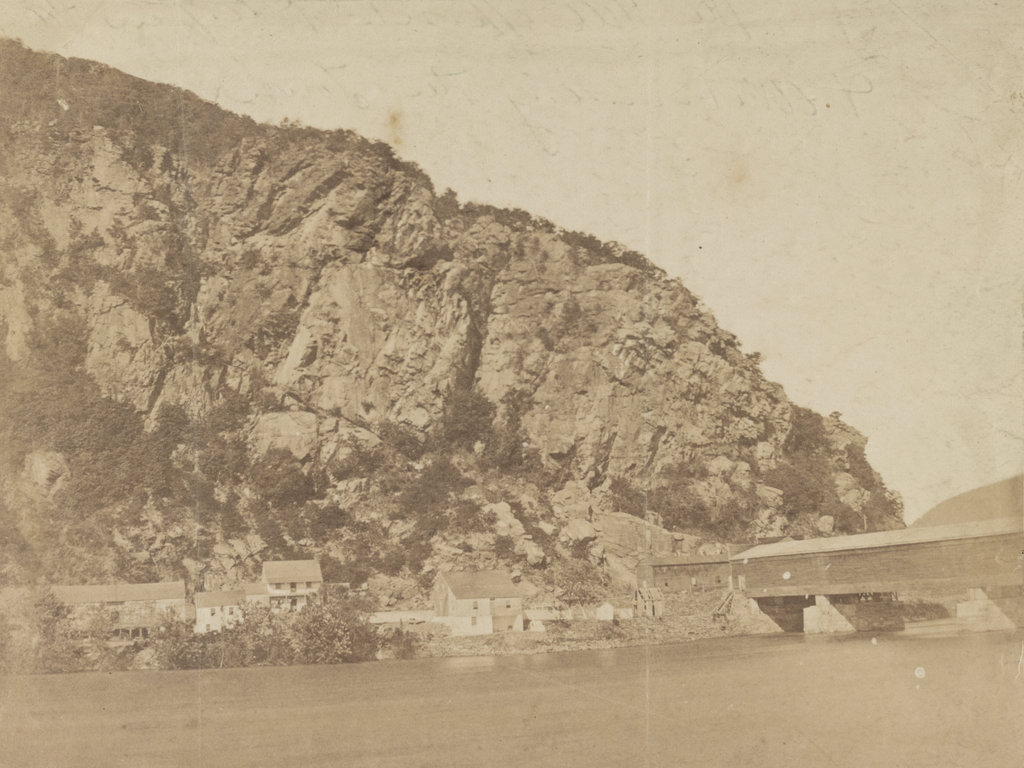

From Lexington, the British continued on their way to Concord, where they began searching for the hidden supplies. Three of the companies ended up here at the North Bridge, which they guarded while other soldiers continued to search. However, by this point the colonial militiamen had begun assembling in a field on the west side of the bridge, visible in the distance on the right side of this scene. This led the outnumbered British to withdraw across the bridge to the east side of the river, here in the foreground. They briefly attempted to tear up the planks of the bridge, but they soon abandoned this effort.

The colonial forces, under the command of Colonel John Barrett, advanced on the bridge from the west, although they were under orders to not fire unless fired upon. Captain Walter Laurie, who commanded the British forces here at the bridge, never gave an order to fire, but some of his men opened fire, killing two militiamen. This prompted the colonists, who were by this point positioned on the west bank of the river, to return fire. In the process, three British soldiers were killed, nine were wounded, and the rest of them began retreating back to the center of Concord. The entire battle took less than three minutes, but it marked the first victory of any kind for the colonists during the war, and the first British fatalities of the war.

This battle would prove to be the only military engagement in Concord during the war, and within less than a year the British forces had evacuated Boston, never again to return to Massachusetts. Here in Concord, life steadily returned to normal after the war, and in 1788 the original North Bridge was demolished and replaced with a new one, evidently without much regard to its historic significance. However, this new bridge did not last very long; it was removed in 1793 when the nearby roads were rerouted.

With the bridge gone, and the old road becoming pastureland, there was little visual evidence of the battle that had occurred here. Probably the first major celebration here at this site came in 1824, on the 49th anniversary of the battle. The event was marked by a parade to the battlefield, and a speech that was delivered here by Ezra Ripley, the pastor of the First Parish Church. He lived right next to here, in a house that later became known as the Old Manse, and his wife Phebe had witnessed the battle from the house, back when she lived here with her first husband, William Emerson.

Despite this celebration, though, it would be more than a decade before the site of the battle was marked by a permanent monument. In 1835, Ezra Ripley donated some of his property here at the spot where the bridge had once stood, and the following year an obelisk, shown here in these two photos, was added to the site. It stood 25 feet in height, and it was designed by Solomon Willard, whose other works included the much larger Bunker Hill Monument in Boston. It was mostly comprised of granite, with the exception of a marble slab here on the eastern face, which reads:

Here on the 19 of April, 1775, was made the first forcible resistance to British aggression. On the opposite Bank stood the American Militia. Here stood the Invading Army and on this spot the first of the Enemy fell in the War of that Revolution which gave Independence to these United States. In gratitude to God and In the love of Freedom this Monument was erected AD. 1836.

The monument was formally dedicated on July 4, 1837, with a ceremony that included a keynote speech by Congressman Samuel Hoar. However, the event is best remembered for “Concord Hymn,” a poem that was sung here. It was written for the occasion by Ralph Waldo Emerson, the grandson of William Emerson, and it was among his earliest notable literary works. Although he would later be known primarily as an essayist and founder of the Transcendentalism movement, the poem remains perhaps his single best-known work, particularly the opening stanza:

By the rude bridge that arched the flood,

Their flag to April’s breeze unfurled,

Here once the embattled farmers stood,

And fired the shot heard round the world.

At the time, there was still no bridge here, and it would be several more decades before one was finally reconstructed. This ultimately occurred in 1874, in advance of the 100th anniversary of the battle. As part of this project, a new bridge was designed and a new monument was dedicated on the west side of the river, marking the militiamen’s position during the battle. This monument, visible in the distance of both photos, features a bronze statue designed by noted sculptor Daniel Chester French. Known as The Minute Man, it consists of a colonial militiaman leaving behind a plow and carrying a musket, representing the farmers who came to the defense of their country. Beneath the statue is a pedestal, designed by James Elliot Cabot, with the first stanza of Emerson’s poem inscribed on it.

The 1874 bridge was destroyed in a storm in 1888, and it was subsequently rebuilt. This bridge, which is shown in the first photo, stood here until 1909, when it too was destroyed. The next bridge here was a concrete structure, completed later in 1909, and it survived until 1955 before being severely damaged by a flood. Its replacement, which was built in 1956, is still standing today, although it underwent a major restoration in 2005. Unlike the earlier bridges, it is a replica of the original one, and it has remained here at this site for longer than any of its predecessors.

In 1959, the bridge, the monuments, and the surrounding battlefield became part of the Minute Man National Historical Park, which encompasses a number of historic sites relating to the battles of Lexington and Concord. The park gained significant attention during the American bicentennial celebrations, and in 1975 President Gerald Ford gave a speech here at the bridge to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the battle. Today, under the administration of the National Park Service, this scene has remained well-preserved, with few significant changes since the first photo was taken more than a century ago. The site of the battle continues to be a major tourist destination, and the park as a whole draws upwards of a million visitors each year to Lexington and Concord.