The south side of Independence Hall, seen from Independence Square around 1905. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

This view is similar to the one in a previous post, but this one shows the scene horizontally from a little further back, revealing more of the surrounding buildings near Independence Hall. As discussed in that post and another one, Independence Hall was the site of some of the country’s most important events in the years during and immediately after the American Revolution.

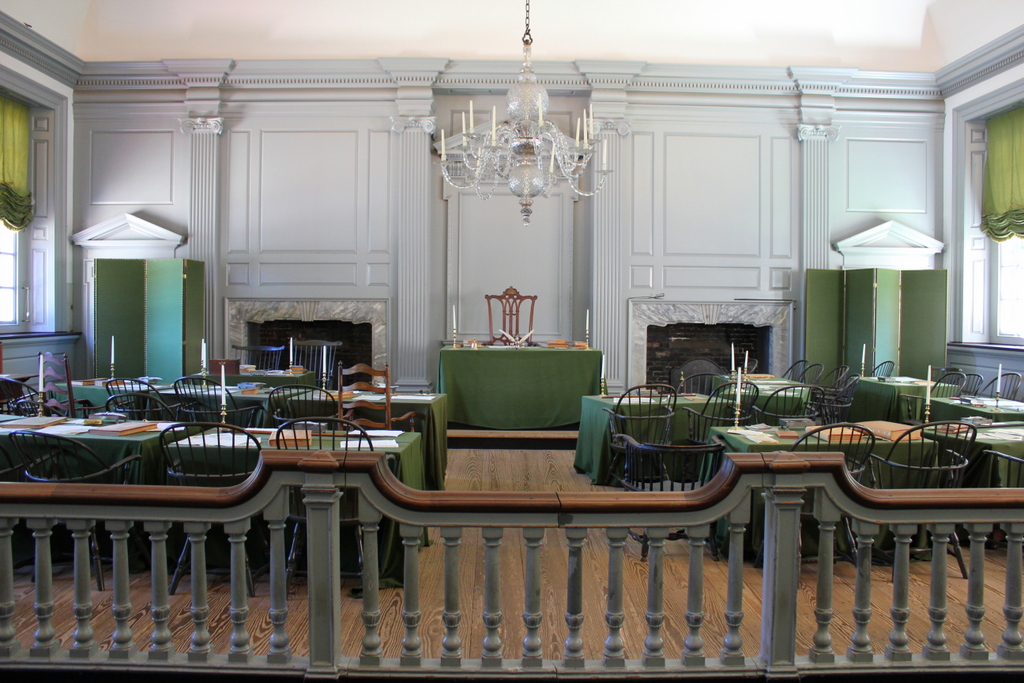

Independence Hall was completed in 1753 as the meeting place of the Pennsylvania colonial legislature, but at the start of the American Revolution it took on a second role as the de facto national capitol. The Second Continental Congress convened here on May 10, 1775, less than a month after the start of the war. The delegates met in the Assembly Room on the first floor of the building, which is located directly to the right of the tower in this scene. The building is most famous for the fact that the Declaration of Independence was voted on and signed here during the summer of 1776, but the building continued to be used by the Continental Congress throughout the Revolution, aside from two interruptions during British occupations of Philadelphia.

Congress finally left Philadelphia in June 1783, after a mob of about 400 soldiers descended upon the building, demanding payment for their wartime service. The state of Pennsylvania refused to deploy its militia to protect Congress, so the delegates left the city on June 21, and reconvened nine days later at Nassau Hall in Princeton, which became the first of several temporary national capitols over the next two years. Independence Hall would never again serve as the federal capitol building, but it nonetheless played another important role in 1787, when delegates from 12 of the 13 states met here for the Constitutional Convention. The result of this four-month convention was the current United States Constitution, which was signed here on September 17, 1787.

In the meantime, Independence Hall continued to serve as the seat of the state government. The federal government also returned to Philadelphia, although not to Independence Hall. Instead, two newer and smaller buildings were constructed, flanking Independence Hall. On the west side, barely visible on the extreme left side of the photos, is Congress Hall. This was the national capitol building from 1790 until 1800, with the House of Representatives occupying the large chamber on the first floor, and the Senate in a smaller chamber on the upper floor. On the opposite side of Independence Hall, on the extreme right side of the photos, is the Old City Hall. On the exterior, it is essentially identical to Congress Hall, and it was originally built to house the city government. However, during the 1790s it was also occupied by the Supreme Court, which had its courtroom on the ground floor.

The state government ultimately left Philadelphia in 1799 and moved to a more central location in Lancaster. Then, a year later, the federal government moved to Washington D.C., despite the best efforts by Philadelphians to retain the city’s status as the capital. No longer needed for governmental purposes, Independence Hall was threatened by demolition during the early 19th century. By this point the original wooden steeple was already gone, having been removed in 1781 and replaced by a low roof. Then, in 1812 the original wings on either side of Independence Hall were demolished, although the rest of the building was spared a similar fate after the city purchased it from the state in 1816.

It often takes many years before the significance of historic buildings is recognized, and in many cases this comes too late. For Independence Hall, though, it seems that its significance was widely understood by the 1820s. It was around this time that it came to be known as Independence Hall, rather than as the State House, and in 1825 the public square here in the foreground was formally named Independence Square. Three years later, a new steeple was constructed based on the plans of the original one, and it still stands atop the tower today.

By the time the first photo was taken around 1905, this scene had undergone further changes. Most significantly, the buildings that had replaced the old wings in 1812 were demolished in 1898, and new wings were constructed as replicas of the originals. Another change would come two years after the photo was taken, when the statue of Commodore John Barry was installed here in Independence Square, as shown in the 2019 photo.

Today, more than a century after the first photo was taken, Independence Hall still looks essentially the same. Both Congress Hall and the Old City Hall have also been preserved, and all three of these buildings are now part of the Independence National Historical Park. However, one notable difference in this scene from the first photo is the row of buildings beyond Independence Hall on the other side of Chestnut Street. All of these buildings, along with two more entire blocks further to the north, were demolished in the mid-20th century in an effort to improve the aesthetics of the area surrounding Independence Hall. However, in an example of historic buildings not being recognized until they are gone, the project included the removal of the remnants of the old President’s House, where George Washington and John Adams had lived during the 1790s. This site, at the corner of Sixth and Market Streets, is now marked by a partial reconstruction of some of the house’s architectural elements.