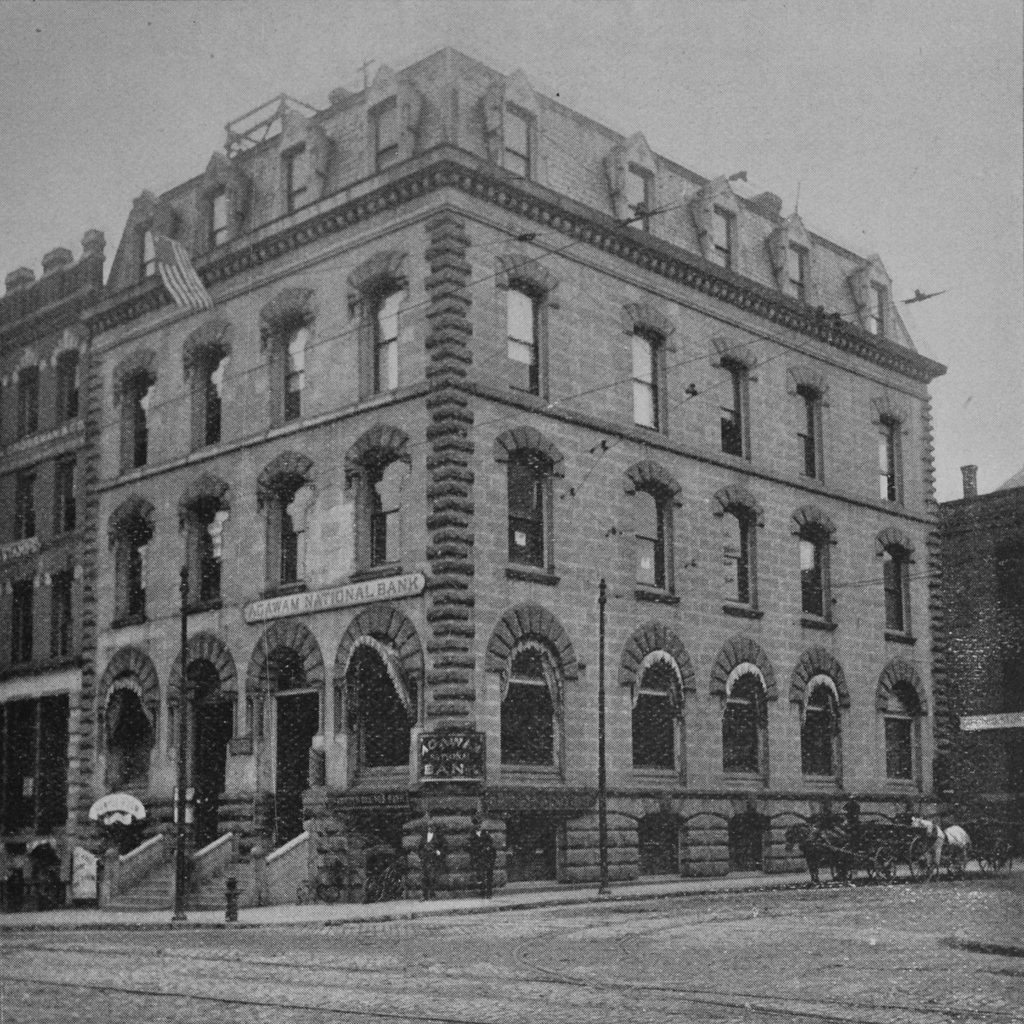

The Agawam National Bank building, at the corner of Main and Lyman Streets in Springfield, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2018:

This building was completed in 1870 to house the Agawam National Bank, which had been established in 1846 and had previously occupied an older building here on this spot. The new building was designed by Henry H. Richardson, a young architect who would go on to become one of the leading American architects of the late 19th century. Although best-known today for Romanesque-style churches, railroad stations, and government buildings, Richardson’s early works included a mix of relatively modest houses and commercial building, many of which bore little resemblance to his later masterpieces.

Richardson’s first commission had been the Church of the Unity here in Springfield, which he had earned in part because of a college classmate, James A. Rumrill, whose father-in-law, Chester W. Chapin, was one of the leading figures within the church. Chapin was also the president of the Western Railroad, and when the railroad needed a new office building, Richardson received the commission without even having to enter a design competition. This building, which stood just a hundred yards to the north of here, was completed in 1867, and two years later he was hired to design a new building for the Agawam National Bank. In what was likely not a coincidence, Chapin had been the founder of this bank, and by the late 1860s, Richardson’s friend James A. Rumrill was sitting on its board of directors.

The design of the Agawam National Bank bears some resemblance to the railroad office buildings. Both were constructed of granite, and they both had raised basements, four stories, and mansard roofs. However, while the railroad building was purely Second Empire in its design, the bank featured a blend of Second Empire and Victorian Gothic elements. Perhaps most interesting were the rounded arches on the ground floor. Although this building could hardly be characterized as Romanesque in its design, these arches bear some resemblance to the ones that he would later incorporate into his more famous works of Romanesque Revival architecture.

Architectural historian and Richardson biographer Henry-Russell Hitchcock did not particularly care for the design of the bank building, criticizing its “square proportions, crude monotonous scale and hybrid detail,” and describing it as a “hodge-podge” that was “pretentious and assertive.” However, he did concede that the building’s virtues “are more conspicuous if one does not look at it so carefully and so hard. To a casual glance, it must have had certain granite qualities of solid mass and strong regular proportions which tend to disappear when it is studied in detail.”

These “qualities of solid mass” likely served the bank well, since 19th century financial institutions often constructed imposing-looking buildings in order to convey a sense of strength and stability. As shown in the first photo, the Agawam National Bank was located on the right side of the first floor, but the building also housed other tenants, including the Hampden Savings Bank, which occupied the basement. These two banks had shared the same building since Hampden Savings was established in 1852, and they would remain here together until 1899, when Hampden Savings moved to the nearby Fort Block.

Agawam National Bank remained here in this building until the bank closed around 1905. By this point, its architecture was outdated, with trends shifting away from thick, heavy exterior masonry walls. The advent of steel frames in the late 19th century had enabled commercial buildings to be taller while simultaneously having thinner walls, and this allowed for large windows with plenty of natural light. The bank building was ultimately demolished around 1923, and it was replaced by a new five-story building that exemplified this next generation of commercial architecture.

Known as the Terminal Building, it was the work of the Springfield-based architectural firm of E. C. and G. C. Gardner, and it was completed around 1924. It was built with four storefronts on the ground floor and offices on the upper floors, and it was designed to support up to seven stories, although these two additional stories were never constructed. Today, the building still stands here, with few exterior changes. It is a good example of early 20th century commercial architecture here in Springfield, and in 1983 it became a contributing property in the Downtown Springfield Railroad District on the National Register of Historic Places.