The house at 84 Westminster Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2017:

Elihu H. Cutler was born in 1856 in Ashland, Massachusetts, and was the son of grist mill owner Henry Cutler. Like his father, Elihu was involved in the grain business as a young adult, but he was more interested in mechanical engineering. Despite having just a high school education, in 1887 he became the treasurer and general manager of the Brooklyn-based Elektron Elevator Company, where he worked under the prominent inventor and company president Frank A. Perret.

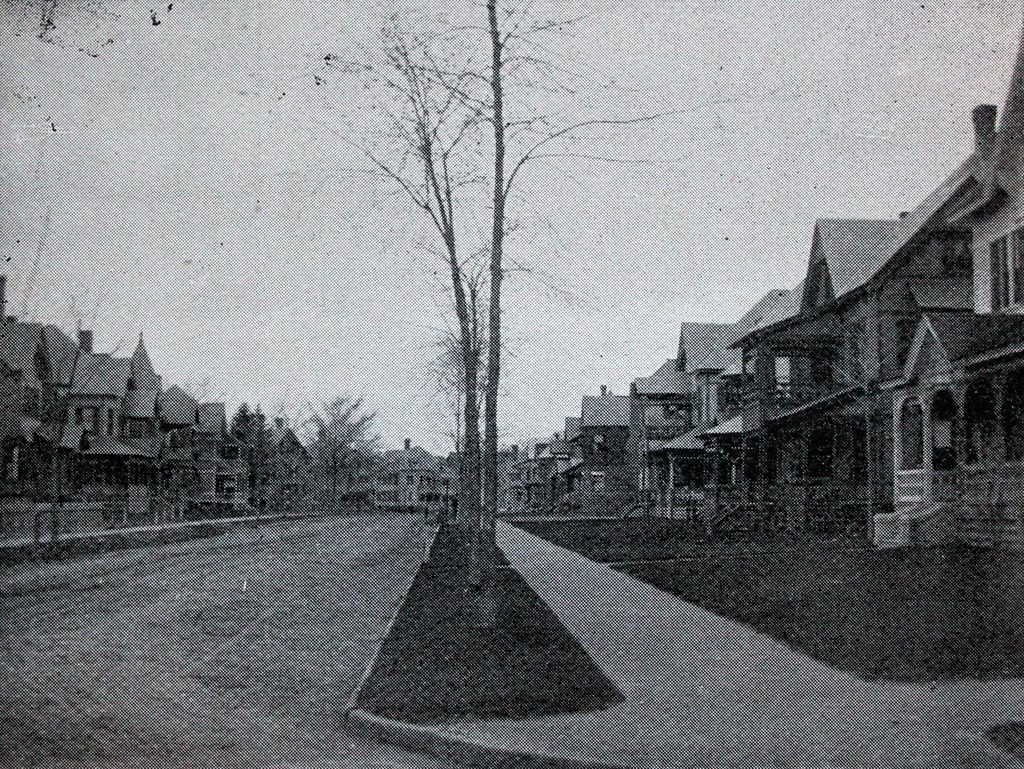

In 1891, Perret moved the company to a new facility on Wilbraham Road in Springfield. Cutler also moved to Springfield, along with his wife Hattie and their three children, and they purchased this newly-built house in the fashionable McKnight neighborhood, just a short walk from the Elektron factory. At the time, Queen Anne style architecture was popular for upscale homes, and their house included many of the style’s common features, including an irregular design, a large front porch, a turret, and a variety of siding materials.

One of Cutler’s apprentices at Elektron was Harry A. Knox, a student at the neighboring Springfield Industrial Institute. Before he was even out of school, Knox had already begun designing and building automobile prototypes, and a few years later in 1900 he founded the Knox Automobile Company. Cutler was apparently impressed with Knox, because he joined the new company as vice president, and he and Knox put their mechanical engineering abilities to work in developing early automobiles.

A few years later, Cutler left the elevator business in order to focus on automobiles. He sold his interest in Elektron to the Otis Elevator Company, and ultimately ended up as the president of Knox, whose main factory was located directly across the street from the Elektron facility on Wilbraham Road. Knox was just one of the many new companies in the rapidly-growing automobile industry, and some of these companies formed the Association of Licensed Automobile Manufacturers. Cutler went on to become the association’s president, and in this capacity he was involved in an unsuccessful legal dispute over patent rights with an upstart rival, Henry Ford.

As it turned out, the Knox and Ford companies were on two completely different trajectories, and by 1915 Knox had discontinued its production of automobiles. Cutler ultimately left the industry and returned to his roots in the grain business, serving as vice president of the Cutler Company, a wholesale grain firm. He and Hattie lived here in this house until 1927, when they moved to New York City.

By 1930, the house was owned by Mary A. Burke, a 59-year-old widow who had immigrated to the United States from Ireland as a child. She lived here with five of her adult children, all of whom were unmarried. Two of her daughters, Mary and Katherine, worked for a lumber company, and her other two, Angela and Frances, were teachers. Her son, Thomas, also lived here, and he worked as a lawyer. Mary died in the 1930s, but her children were sill living here when the first photo was taken at the end of the decade.

The Burke children sold the house in 1950 to Reverend James H. Hamer, who lived here for many years and served as pastor of Faith Baptist Church. During this time, the house has been well-maintained, and the exterior has hardly changed since the Cutler family moved in over 125 years ago. The adjacent apartment building, completed in 1901, is also still standing, and is one of a handful of apartment buildings in a neighborhood that is predominantly single-family and two-family homes. Today, both buildings, along with the rest of the neighborhood, are now part of the McKnight Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.