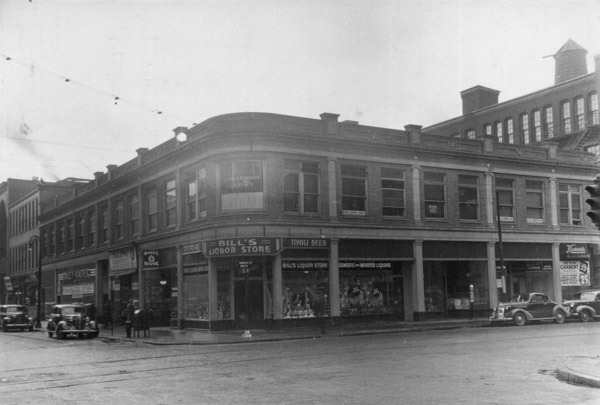

The building at the southwest corner of Main and Worthington Streets in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The scene in 2017:

The skylines of American cities underwent dramatic changes at the end of the 19th century, thanks in large part to new developments in engineering and construction. Prior to this time, the height of commercial buildings was limited by a variety of practical factors, not least of which was the difficulty in supporting upper floors. Load-bearing masonry walls worked well for low-rise buildings, but taller buildings required increasingly thick exterior walls, sacrificing valuable ground-floor retail space in order to build higher. Such buildings could reach impressive heights, such as Chicago’s 17-story Monadnock Building, which was completed in 1894, but here in Springfield most masonry buildings did not exceed four or five stories.

By the late 19th century, though, inexpensive steel helped to revolutionize the way buildings were constructed. With steel frames, buildings were no longer limited to the capacity of load-bearing masonry, enabling the rise of modern skyscrapers. The first of these, the 10-story Home Insurance Building in Chicago, was completed in 1885, and it did not take long for the trend of steel-frame skyscrapers to reach Springfield. This location at Main and Worthington Streets has previously been the site of a brick, two-story commercial block that burned in 1893. Its owner, Andrew Whitney, soon set out on an ambitious project to replace it by building a six-story steel building that would become the first steel-framed building in Springfield and among the first in New England.

Construction on the building began in 1894, although it would not ultimately be completed for another three years. Historian George C. Kingston, in his book William Van Alen, Fred T. Ley and the Chrysler Building, attributes this delay to a combination of factors, including the new style of construction, concerns from city officials, and the fact that Whitney, a real estate developer from Fitchburg, designed the building himself, instead of hiring a professional architect. As a result, the building did not conform to architectural trends of the era, instead featuring a relatively plain exterior without the classically-inspired ornamentation that was common at the time. However, despite local fears that the walls were too thin to support the six-story building, it was completed in 1897 and would stand here for more than 75 years.

A 1913 building directory shows a wide variety of tenants here. On the ground floor, the Main Street facade had two storefronts, with Miner & Co. cigars, magazines, soda, and confectionery in one, and W. L. Douglas shoe company in the other. There were another seven stores on the Worthington Street side, including a barber shop, a jewelry store, and a haberdasher. Above these shops, the upper five floors housed offices, which were served by two elevators – another late 19th century development that helped make skyscrapers a practical reality. These offices included attorneys, dentists, physicians, realtors, and other professionals, for a total of 50 individuals and corporations that had offices here in the building.

By the time the first photo was taken in the late 1930s, first-floor tenants included jeweler P. B. Richardson on the left side, Clear-Weave Hoisery Stores in the center, and the Stearns Curtain Shop in the storefront on the corner. The building would stand here for several more decades, but it was severely damaged by a fire in December 1974, and was demolished the following year. Several years later, the entire block along Main Street between Bridge and Worthington Streets was redeveloped, and a new federal building was constructed here in 1981. The government sold the property in 2009, following the completion of the new federal courthouse on State Street, but the old building underwent a significant renovation and is now used for offices.