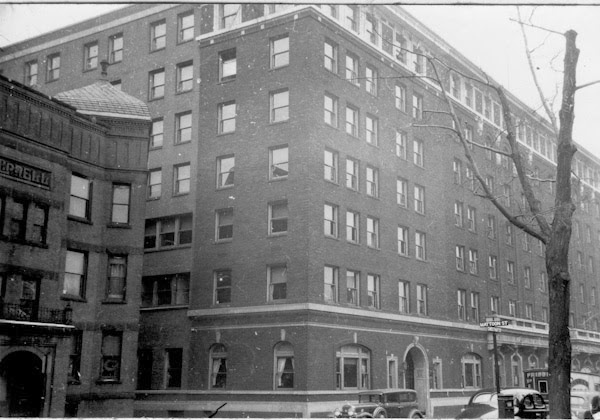

The YMCA building at 114-122 Chestnut Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The building in 2018:

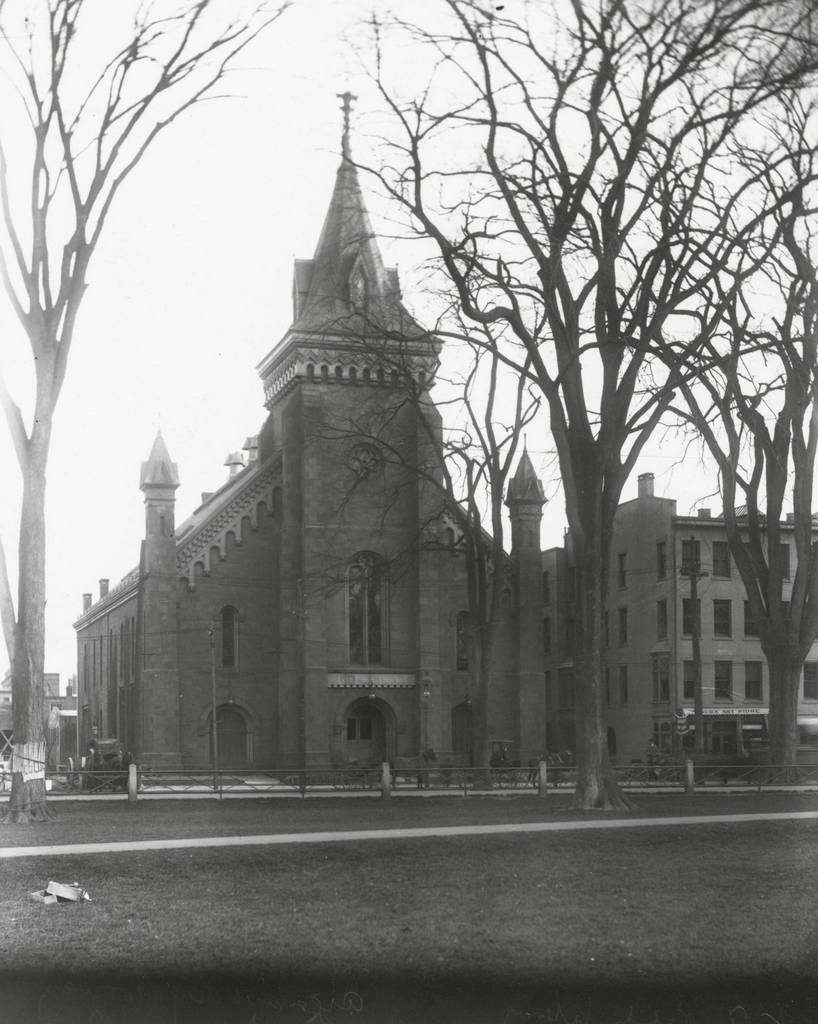

The Springfield Young Men’s Christian Association was established in 1852, the same year that Springfield became a city. It was only the second YMCA in the country, and the fourth in the world, after London, Montreal, and Boston. After having several locations during the 19th century, the Springfield YMCA moved into a building of its own, at the corner of State and Dwight Streets. However, within just 20 years it had become too small, and the organization was in need of a new building.

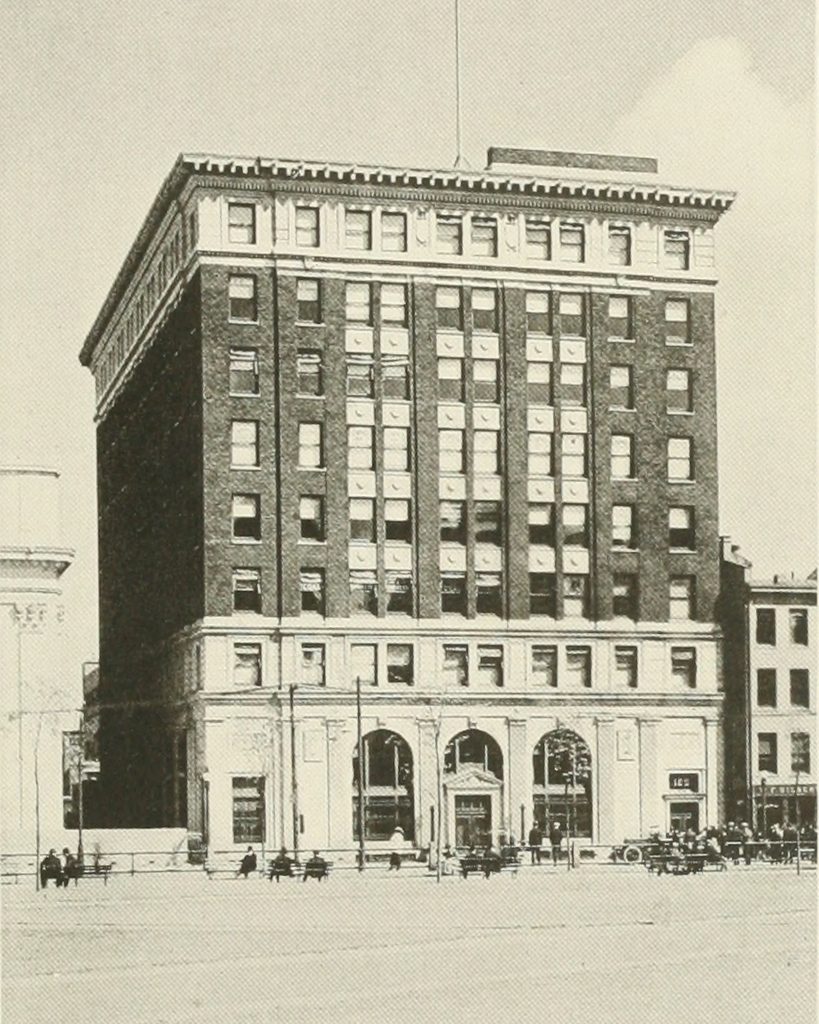

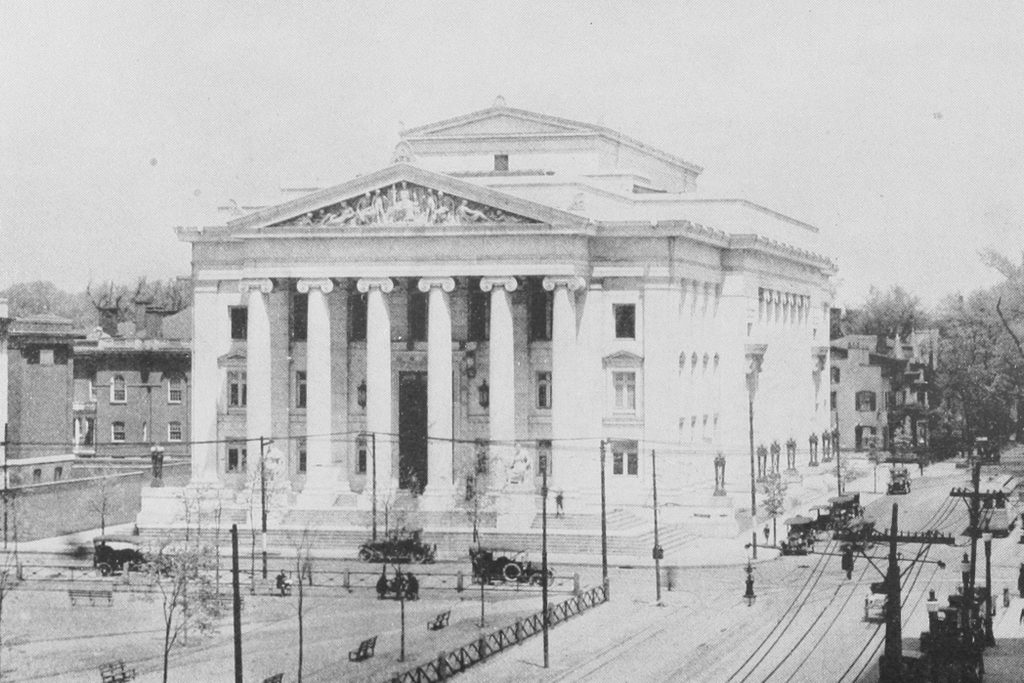

The new building, seen here in these two photos, was completed in 1916 at the corner of Chestnut and Hillman Streets. It was designed by the Chicago-based architectural firm of Shattuck and Hussey, and it featured a brick Classical Revival exterior that was similar to the neighboring Hotel Kimball, which was built only a few years earlier. At the time, though, the YMCA building was smaller than its appearance in these photos. Its Chestnut Street facade originally only extended as far as the large gap between the windows, but the remaining third of the building was added in 1929. Its architecture matched the older section, but this sizable addition eliminated the symmetry of the original design.

The lower floors of the seven-story building housed recreational facilities, while the upper floors were built with hotel rooms. Over time, though, these rooms were used more by long-term boarders than by hotel guests. The 1940 census, which was done only a year or two after the first photo was taken, shows 173 residents living here. All of them were men, and most were single and in their 20s and 30s. They held a wide variety of working-class jobs, with a random sampling of one of the pages showing a post office clerk, maintenance engineer, painter, phonograph operator, cashier, dish washer, mechanic, chauffeur, draftsman, and variety story display man, among many other occupations. Many other residents were employed at the nearby Springfield Armory, which was then in the process of increasing production on the eve of America’s entry into World War II. Overall, most of the residents earned somewhere in the range of $500 to $1,500 per year ($9,000 to $27,000 today), although at least one – decorative metal company owner Roland Anderson – earned over $5,000 (over $90,000 today).

The YMCA would remain here in this building until 1968, when its current building opened on 275 Chestnut Street. The older building was later converted into a 99-unit apartment building, and it is now owned by SilverBrick, which has recently renovated the interior. However, despite these changes in use, the exterior has hardly changed since the first photo was taken, and the building is now a contributing property in the Apremont Triangle Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.