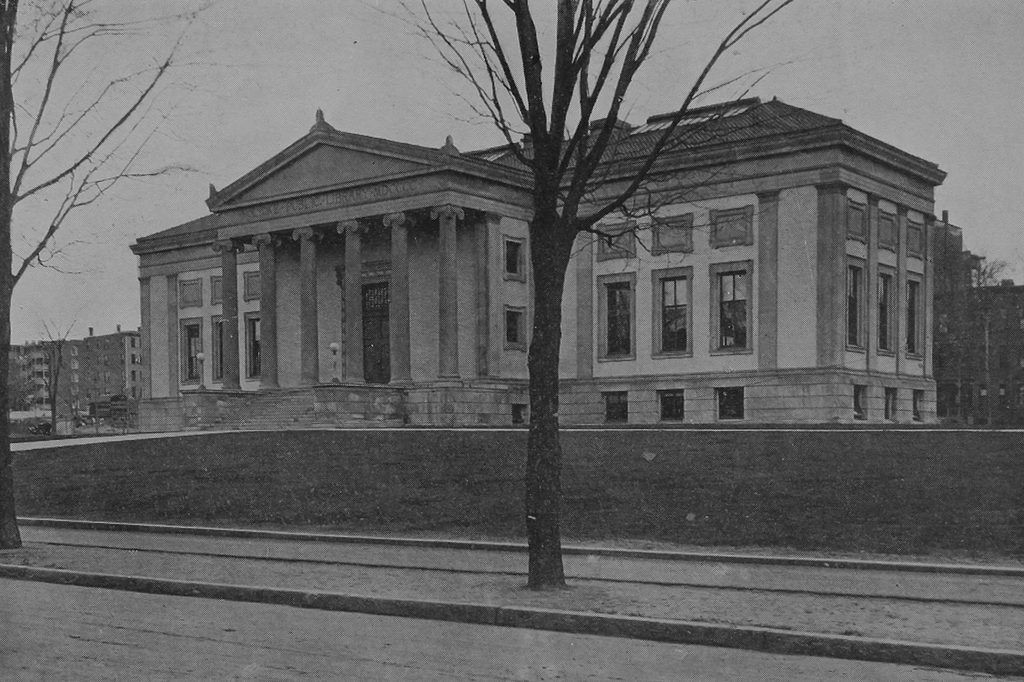

The building at the corner of Maple and Dwight Streets in Holyoke, around 1910. Image from Holyoke: Past and Present Progress and Prosperity (1910).

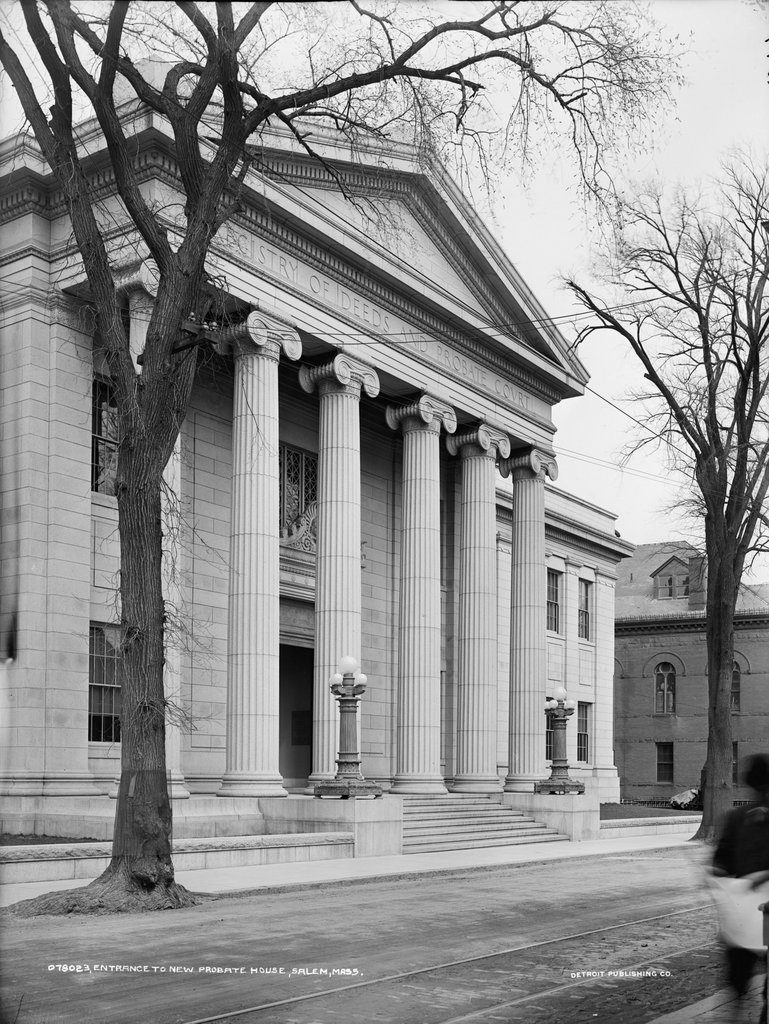

The building in 2017:

This large, mixed-use commercial and residential building stands at the corner of Maple and Dwight Streets in downtown Holyoke. It is just a block away from City Hall and the central business district of High Street, and it overlooks Hampden Park, which is located directly across Dwight Street from here. Although completed more than a century ago, the building’s appearance seems very modern in many ways. With its boxy design, numerous balconies, and relative lack of ornamentation, it could almost pass for an early 21st century condominium complex that was made to look old, instead of an early 20th century building that actually is old.

The first photo shows the building soon after its completion in 1910, and was published in Holyoke: Past and Present Progress and Prosperity, along with a glowing description of the new building:

There is no doubt about the fact that Holyoke is progressing along the building line as well as in the many other lines, for with the erection of the Phoenix building during 1909 and 1910, Holyoke has gained a great modern and metropolitan structure, comparing favorably with the most modern of the buildings in larger cities. Located in the commercial heart of the city, facing Dwight and Maple streets, it is ideal for both business and residential purposes. The outward structure is of brick. The entire weight of the building is sustained by a heavy steel frame. This steel frame is covered with Portland cement construction. The floors are of Portland cement. All partitions are made of hollow tile blocks. There are six stories, and a basement of one hundred and twenty feet both on Dwight and Maple streets. There are nine stores of handsome and substantial finish and most stylish entrances and show windows.

There are many offices, each provided with hot and cold water, ample light and air; when one considers the central location of these offices and that this building is fireproof throughout together with elevator service, then it is realized that here is a good place to do business. A word should be said about the plumbing. This work is being done by the well known firm of Carmody & Sullivan, and is of the best and latest constriction for this kind of a building.

Besides the offices there are here many first class chambers, arranged to suit the most critical, an ample supply of light, air, hot and cold water, new furniture and fixtures are provided and of course the fireproof qualities and the elevator apply to this part of the building also. These rooms are rented in single or suite with or without private bath. On the two upper floors, where the view and the air are still better and it is quieter, there are a number of apartments ranging from two to five rooms, all fitted up with the latest improvements. Inspection of this modern and fireproof building is invited. The owners are the Phoenix Realty Associates, the trustees of which are E. L. Lyman, E. C. Bliss and J. J. Ramage.

Mr. L. L. Bridge of Springfield was the architect and engineer. Mr. F. H. Dibble took the contract to finish the building when the steel and cement work was finished.

The 1920 census shows a number of residents here in this building, including 14 families who rented apartments. These included one of the building’s owners, Edmund C. Bliss, who worked as the secretary and assistant treasurer of the Springfield Blanket Company. Other tenants included a mechanical engineer, a sales manager, a railroad freight agent, the physical director of the YMCA, a merchant, a tailor, and several foremen who worked in factories. Most of these families consisted of just a husband and wife living in an apartment, but there were also several families that had children.

However, the majority of the building’s residents during the 1920 census were listed as lodgers, presumably living in the single rooms that were described in the excerpt above. There were a total of 80 such lodgers, nearly all of whom were either single or widowed. In a city that was largely comprised of immigrant factory workers during this period, nearly all of these lodgers were born in the United States, although many were the children of immigrants. Like those who rented apartments, the lodgers tended to hold middle-class jobs, including office clerks, machinists, milliners, dressmakers, stenographers, and one resident was even listed as a bank vice president.

By the 1940 census, the building still housed a variety of middle class residents. None were listed as lodgers, although nearly all of them lived alone, and were either single or widowed. Monthly rents ranged from $15 to $75 (about $275 to $1,370 today), but most tenants paid around $20 to $25 (about $365 to $457 today). Of those who worked for a full year, annual salaries ranged from $600 (around $11,000 today) for an attendant at a state school, to $3,280 (around $60,000 today) for a mechanical inspector who worked at an army air base.

Today, more than a hundred years after the first photo was taken, Holyoke is no longer the prosperous industrial center that it had been during the first half of the 20th century. However, the city has many historic buildings that are still standing, including the Phoenix Building. It has lost the balustrade atop the roof, and the ground-floor storefronts have been altered, but overall it has remained well-preserved over the years, and it survives as a good example of an early 20th century mixed-use development here in Holyoke.