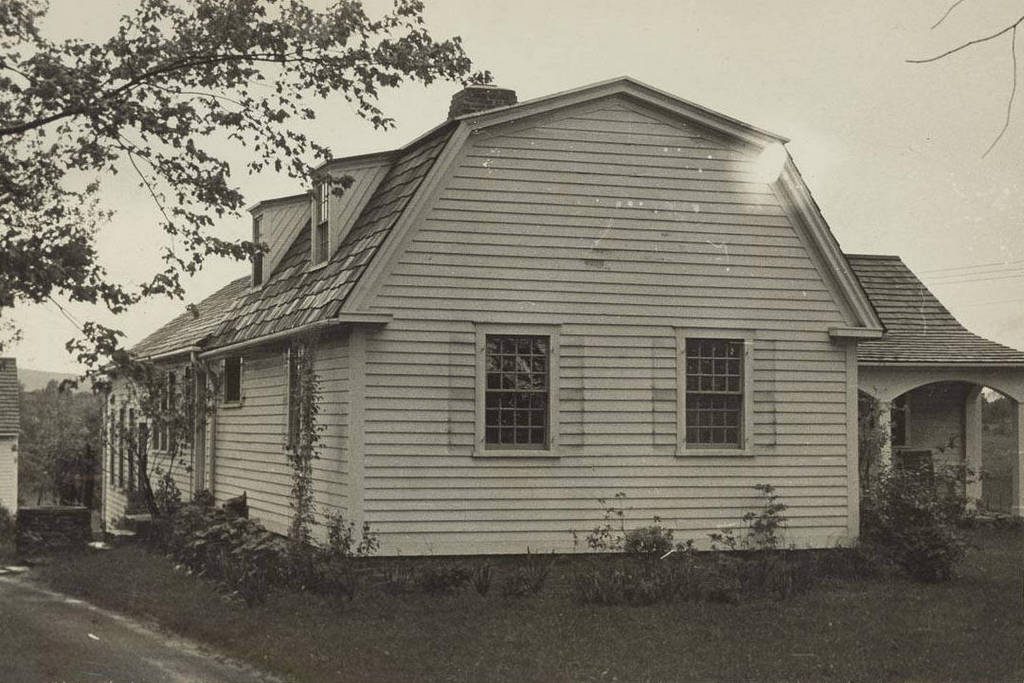

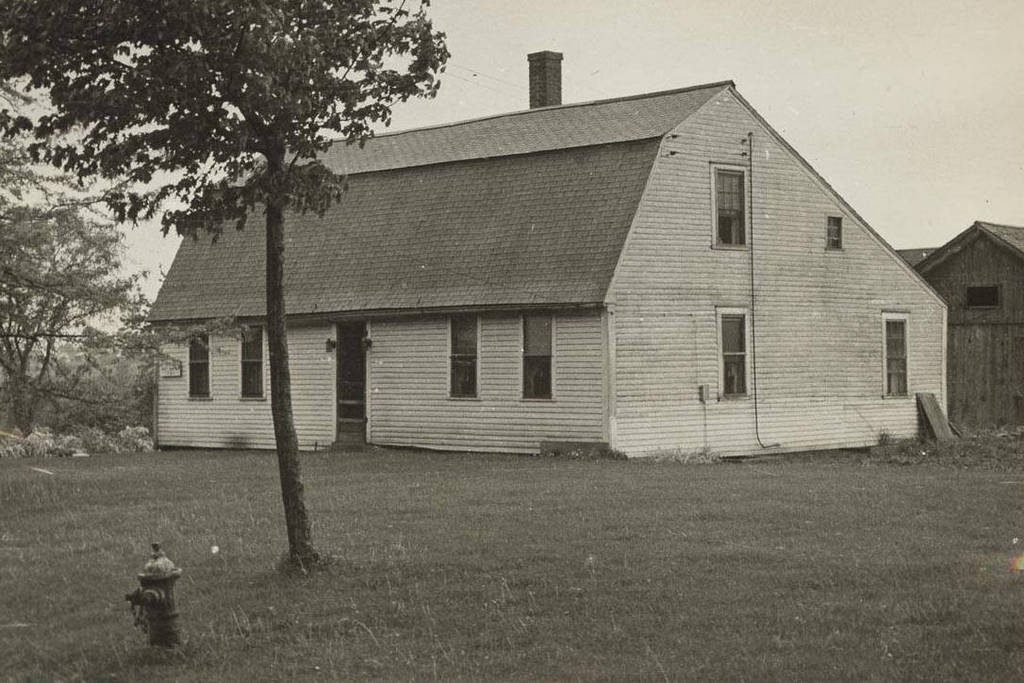

The Oliver Ellsworth Homestead at 778 Palisado Avenue in Windsor, around 1920. Image from Old New England Houses (1920).

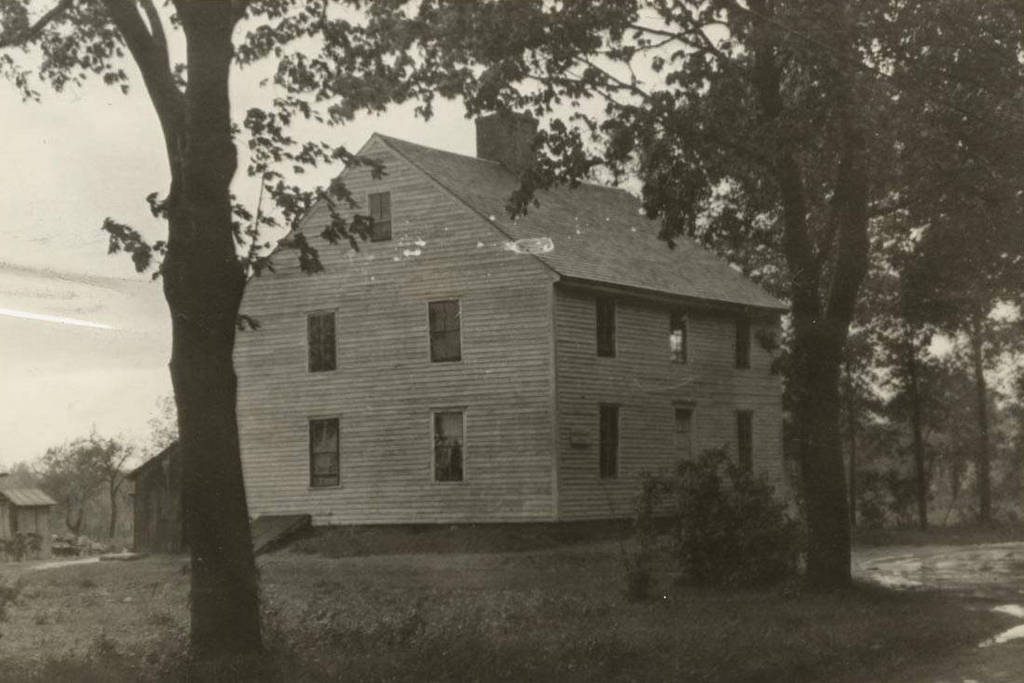

The house in 2017:

This house was built in 1781 for Oliver Ellsworth, a lawyer who was, at the time, a member of the Continental Congress. He was well on his way to becoming one of Connecticut’s most prominent figures of the late 18th century, and served as one of the state’s representatives in Congress from 1778 to 1783. Along with this, he held a variety of state offices, but perhaps his most important contribution to history came in 1787, when he was one of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention. Although he left the convention early and did not sign the finished Constitution, he played a key role in resolving the contentious issue of how states would be represented in the new Congress. He worked with fellow Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman to create the Connecticut Compromise, which established the current structure of Congress, with two senators per state, plus a varying number of representatives that was based on population.

Two years later, Ellsworth became one of Connecticut’s first two senators, serving from 1789 to 1796. During this time, he was largely responsible for writing the Judiciary Act of 1789, which established the federal court system. In 1796, he became the head of this court system when George Washington appointed him as the nation’s third Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Washington’s previous choice for the position, John Rutledge, had been rejected by the Senate, but Ellsworth was confirmed by a unanimous vote. That same year, he also gained 11 electoral votes in the presidential election, finishing a distant sixth behind John Adams. He served as the Chief Justice until his retirement in 1800. During this time, John Adams sent him to France as part of a delegation to negotiate with Napoleon, with Ellsworth and the other Americans ultimately reaching an agreement that avoided war between the two countries.

Ellsworth lived in this house for over 25 years, and both George Washington and John Adams made visits here during their presidencies. Ellsworth and his wife Abigail raised nine children here, including twins William Wolcott Ellsworth and Henry Leavitt Ellsworth. Born here in 1791, they both achieved prominence of their own. William followed in his father’s footsteps, becoming a lawyer and politician. He married Emily Webster, the daughter of dictionary writer Noah Webster, and he served as a Congressman from 1829 to 1834, the governor of Connecticut from 1838 to 1842, and as a judge on the state Supreme Court from 1847 to 1861. Likewise, Henry was involved in politics, serving briefly as mayor of Hartford before spending a decade as the commissioner of the U.S. Patent Office, from 1835 to 1845.

The exterior of the house has not changed much since Ellsworth’s lifetime. The addition on the right side came in 1788, presumably to accommodate the growing family, although the pillars and the overhanging roof were added later in the 1800s. After his death in 1807, the house remained in his family for nearly a century, until 1903, when it was given to the Connecticut chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The organization still owns the house, and it is preserved as a museum, with tours offered by appointment. Because of its significance as the home of one of the Founding Fathers, the house was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1970 and designated a National Historic Landmark in 1989.