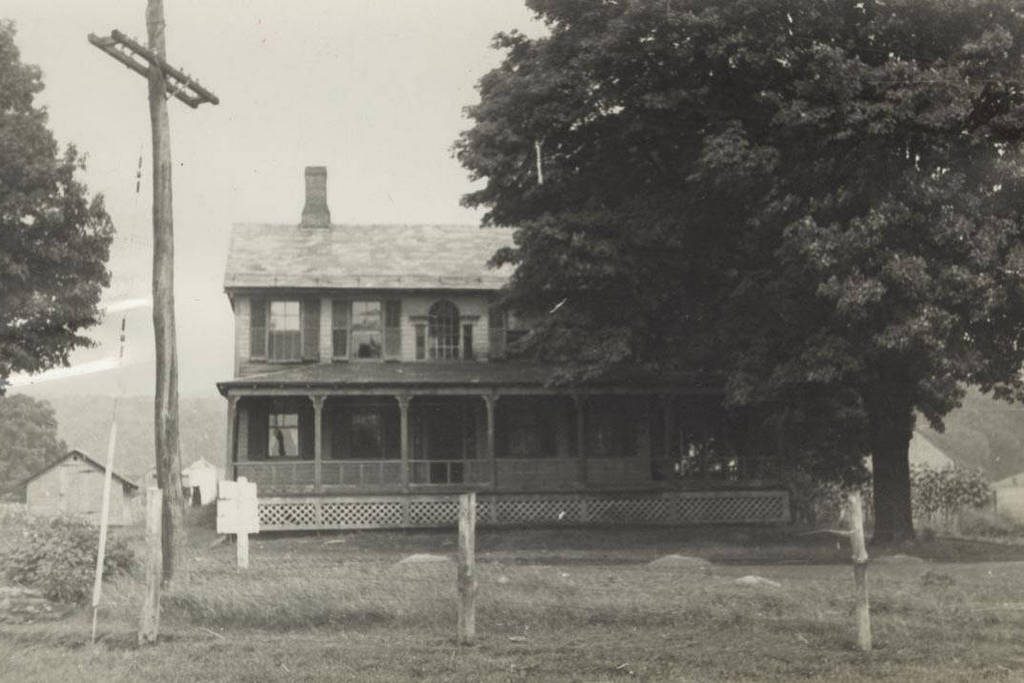

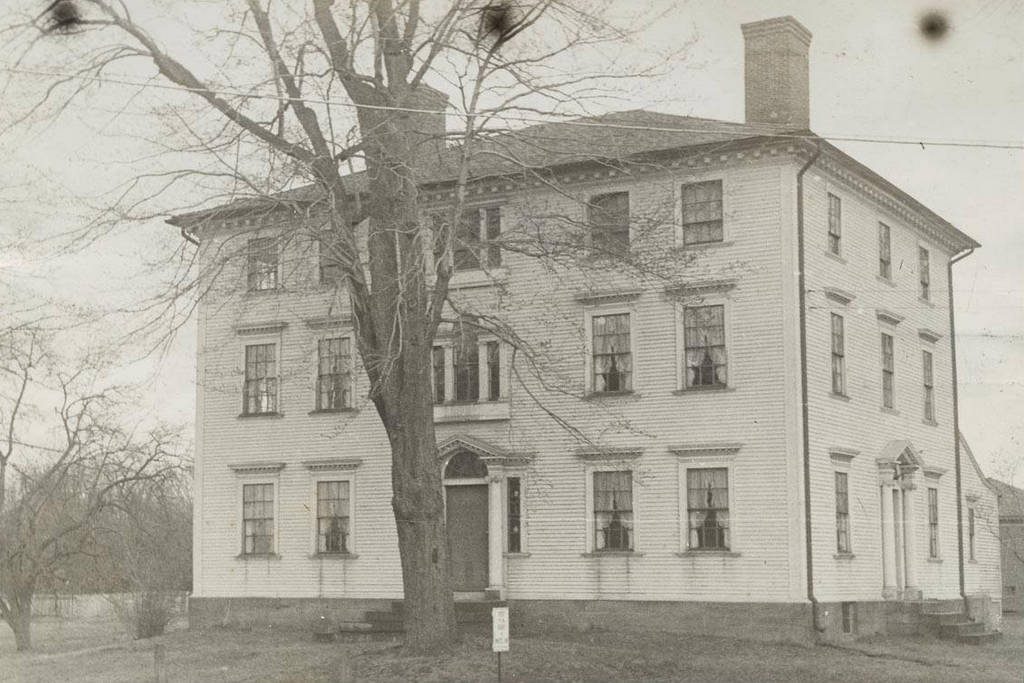

The house at 1876 Main Street, at the corner of Sullivan Avenue in South Windsor, around 1935-1942. Image courtesy of the Connecticut State Library.

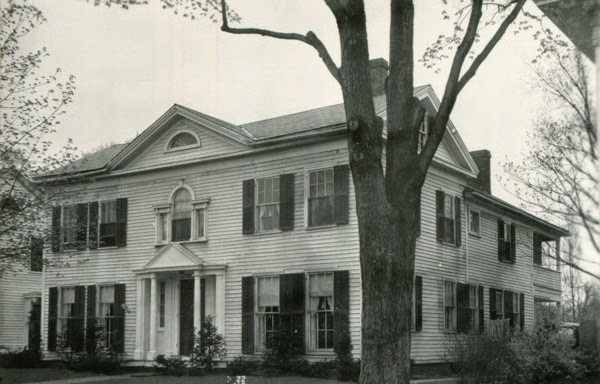

The house in 2023:

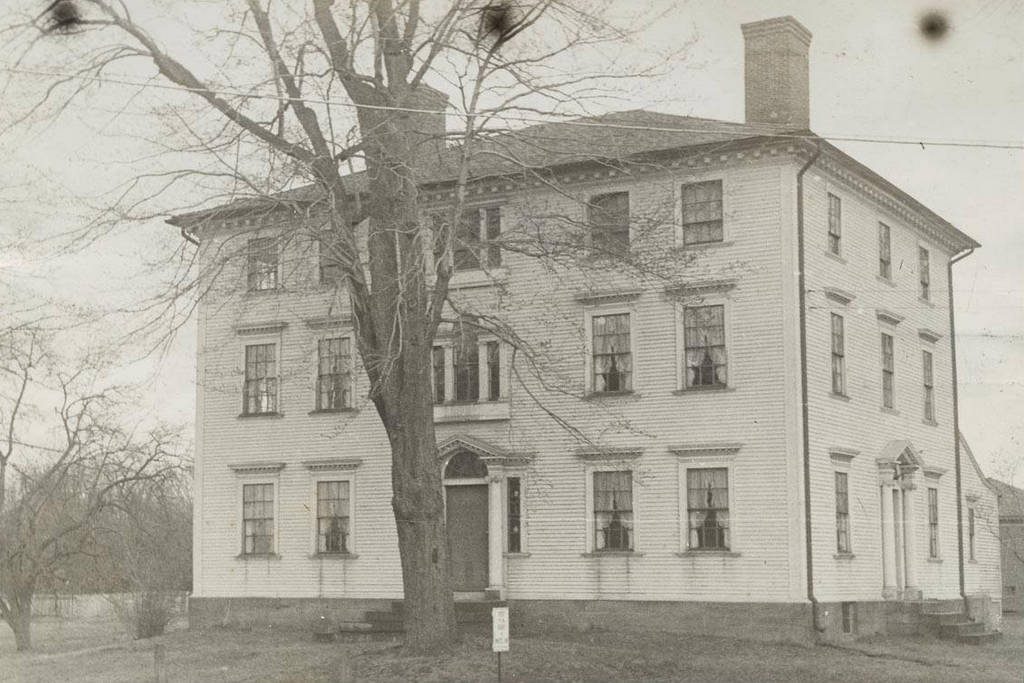

During the late 18th and early 19th centuries, many wealthy New Englanders built large, ornate, three-story mansions such as these, usually with symmetrical facades, hip roofs, Palladian windows, and other Federal-style architectural features. However, most of these mansions were built in prosperous coastal seaports, such as Salem, Providence, and Portsmouth, and they were rarely seen in inland towns. This house in South Windsor, though, is a rare exception, and it stands out among the otherwise more conservatively-designed homes in the village of East Windsor Hill.

The house was built between 1788 and 1790 for John Watson, a prominent local merchant and farmer. Although he did not live in one of the major seacoast ports, he nonetheless styled his home after the leading merchants in those places, and hired architect and builder Thomas Hayden to design it. The result was one of the finest late 18th century homes in the area, with an elegant exterior and interior that reflected Watson’s wealth and his standing in the town. The house even included such luxuries as a four-hole outhouse, which is still standing in the backyard.

A Yale graduate of 1764, John Watson married his wife Anne Bliss three years later, and they had eight children. Around the same time that he built his house, he was serving as a delegate to the state’s U.S. Constitution ratification convention, voting yes in favor of ratifying the new national constitution. He was in his mid-40s at the time, and John went on to live here for the rest of his life, until his death in 1824. Anne died three years later, and their son Henry inherited the property. Born in 1781, he married Julia Reed in 1809, and they had 13 children, who were born between 1810 and 1833.

Several of Henry and Julia’s children would go on to become prominent individuals, in widely varying fields. Their oldest, Henry Jr., graduated from Harvard, but moved to Alabama in the early 1830s and became a lawyer. He became wealthy through his law practice and several business ventures, and he went on to purchase a plantation, becoming one of the largest slaveowners in the state. In the meantime, his younger brother Louis graduated from Yale Medical School and became a successful surgeon, with a career that included serving as a medical director in the Union Army during the Civil War. Yet another Watson brother, Sereno, also graduated from Yale, with a degree in biology. He went on to become a prominent botanist, and served as the curator of the Gray Herbarium at Harvard.

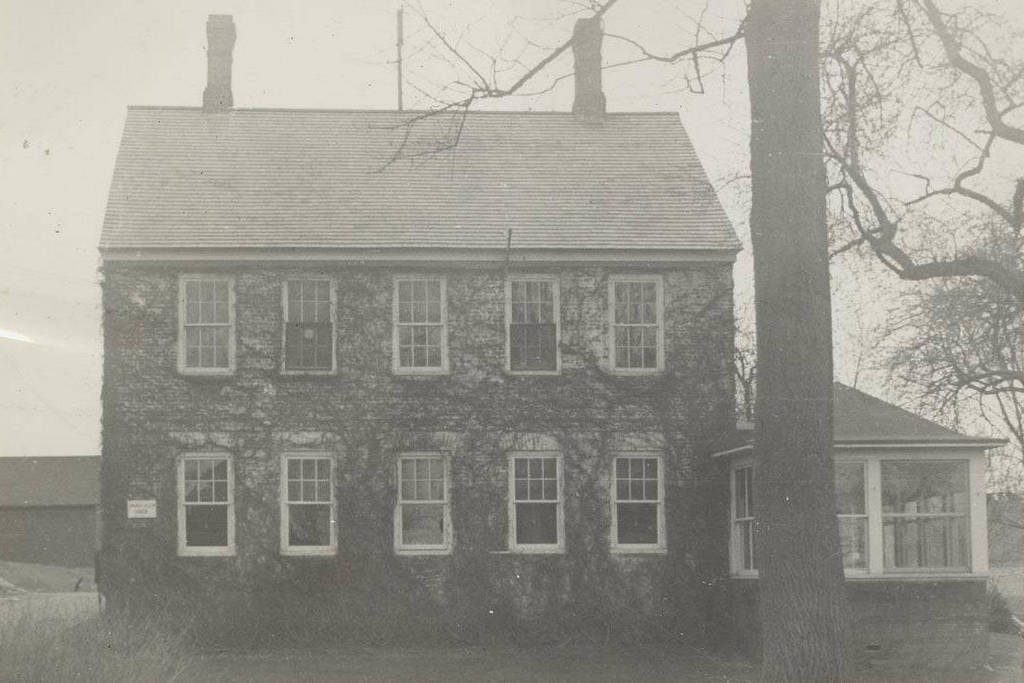

Despite having so many heirs, the house did not remain in the Watson family after Henry’s death in 1848. Instead, it was sold to Theodore E. Bancroft, who probably moved in around the same time as 1853 marriage to Elizabeth Moore. During the 1860 census, he was 32 years old, and was already a moderately wealthy farmer, with real estate valued at $8,000 and a personal estate of $3,815, for a combined net worth equal to over $300,000 today. He and Elizabeth had two children at this point, and he also employed two farm hands who lived here.

By the 1870 census, Bancroft’s net worth had increased to $37,000, or over $700,000 today, and he and Elizabeth had a total of six children. He lived here until his death in 1903, and Elizabeth remained here with her son Frank until her death in 1923, when she was over 90 years old. By this point, the house had already become a prominent landmark because of its seemingly out-of-place architecture, and the first photo was taken only about a decade later, as part of a project to document the state’s historic buildings.

About 80 years have passed since the first photo was taken, but the exterior of the house has not changed much. It was restored in the late 1990s and converted into a bed and breakfast, the Watson House, which has since closed. The exterior of the house was recently restored, including a new coat of paint, and it still stands as a rare example of a three-story 18th century mansion in the region, and it is one of the contributing properties in the East Windsor Hill Historic District on the National Register of Historic Places.