East India Marine Hall on Essex Street in Salem, around 1910-1920. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

The Peabody Essex Museum in Salem is one of the oldest museums in the United States, with a complex lineage that traces back to 1799, with the formation of the East India Marine Society. At the time, Salem was one of the most prosperous seaports in the country, with merchants who were among the first Americans to trade with southeast Asia. The society was established by local captains with several goals, including sharing navigational information, providing aid to families of members who died, and collecting artifacts and other interesting objects from the East Indies. Membership was limited to captains and supercargoes of Salem vessels who had sailed beyond either the Cape of Good Hope or Cape Horn.

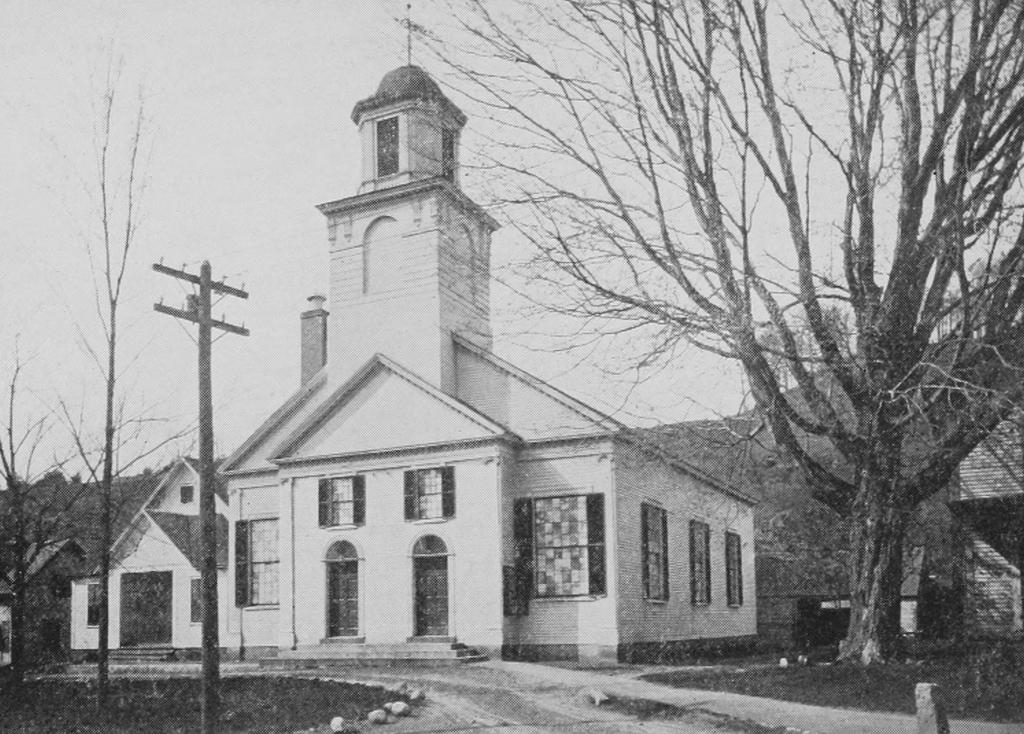

The organization moved into its first permanent home in 1825 with the completion of East India Marine Hall, shown here in these two photos. The building was formally dedicated on October 14 of that year, in a ceremony that was attended by many noted dignitaries. These included President John Quincy Adams; Congressman and former Secretary of the Navy Benjamin W. Crowninshield; Associate Justice Joseph Story of the U. S. Supreme Court; former Senator, Postmaster General, Secretary of War, and Secretary of State Timothy Pickering; and famed navigator and mathematician Nathaniel Bowditch.

The building was designed by Boston architect Thomas Waldron Sumner, and it features a Federal-style design with a granite exterior here on the main facade, which faces Essex Street. Originally, the main entrance was located in the center of the building on the ground floor, and it was flanked by storefronts on either side. These storefronts have long since been altered, but the names of the first two commercial tenants—the Asiatic Bank and the Oriental Insurance Company—are still carved in the granite above the ground floor. The East India Marine Society itself was located on the second floor, which consisted of a large open hall.

Despite the grand celebration for the completion of this building, though, Salem was already in decline as a seaport. Both the Embargo Act of 1807 and the subsequent War of 1812 had crippled Salem’s shipping, and it never fully recovered, with much of the international trade shifting to other northeastern ports, such as Boston and New York. Elsewhere in New England, the region’s economy was transitioning from trade to manufacturing, and Salem’s growth had stagnated by the mid-19th century, even as nearby industrial cities such as Lowell experienced rapid increases in population.

Because of this, the East India Marine Society faced dwindling membership, and by the 1850s it began considering selling objects from its collections in order to remain financially viable. However, prominent London financier George Peabody—a native of the neighboring town of Peabody—intervened, and in 1867 he established a $140,000 trust fund. The museum was then reorganized as the Peabody Academy of Science, for the “Promotion of Science and Useful Knowledge in the County of Essex.” As part of this, the natural history collections of the Essex Institute, which had been established in Salem in 1848, were transferred to the Peabody. In exchange, the Essex Institute received the Peabody’s history collections.

The Peabody Academy of Science continued to use the East India Marine Hall, but over the years it made some significant alterations to the building. In the mid-1880s the museum added a wing, known as Academy Hall, to the southeast corner of the original building. It stands in the distance on the left side of the first photo, and the sign for it is visible just beneath the awning. Then, in 1904 the storefronts were removed and replaced with museum exhibit rooms, and around this time the original front entrance was also closed. A new one-story entryway was then built on the right side of the building, as shown in the first photo. This photo also shows a large anchor in front of the building. It was made sometime around the turn of the 19th century, and it was donated to the museum by the United States Navy in 1906.

In 1915, around the same time that the first photo was taken, the Peabody Academy of Science was renamed the Peabody Museum of Salem. Throughout the 20th century, the museum continued to expand with more additions, reaching as far back as Charter Street on the other side of the block. From here on Essex Street, probably the most visible change was the addition of a large Brutalist-style wing on the left side of the original building, which was completed in 1976.

Then, in 1992 the Peabody Museum of Salem merged with the Essex Institute, forming the Peabody Essex Museum. Since then, its facility has grown even more, with new wings that were completed in 2003 and 2019. This most recent addition, which opened the same year that the second photo was taken, was built on the right side of this scene. It involved the demolition of the old 1904 entryway from the first photo, and now the original East India Marine Hall is almost completely surrounded by newer buildings. However, the main facade has remained largely unchanged throughout this time, and it remains an important landmark in downtown Salem nearly two centuries after its completion.