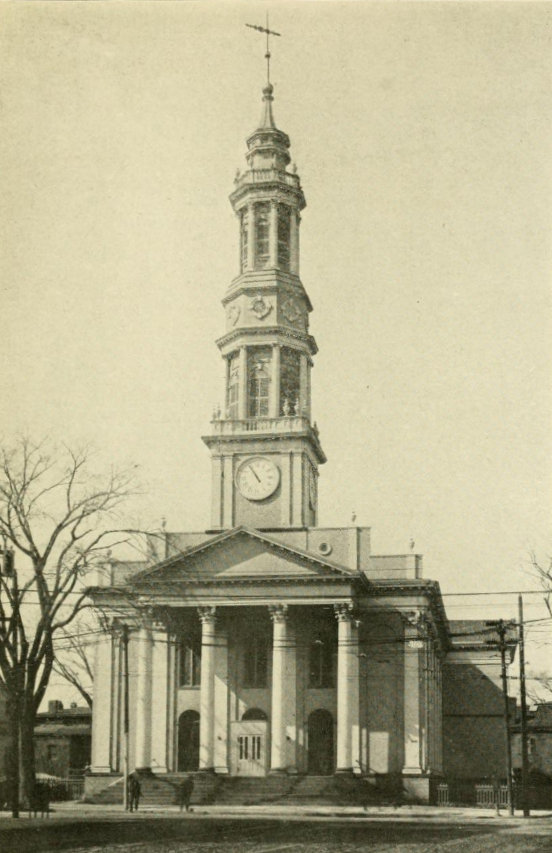

The old Worcester County Courthouse at the corner of Main and Highland Streets in Worcester, around 1908. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The building in 2016:

Geographically, Worcester County is the largest of the 14 counties in Massachusetts, and for many years this building served as the county courthouse. It has been expanded several times over the years, but the original section is the left side of the building. Completed in 1845, it was designed by architect Ammi B. Young, a Greek Revival architect whose other works included the old Vermont State House, the Custom House in Boston, and part of the US Treasury Building in Washington, DC.

When it was first built, the courthouse had a different front, with a typical portico supported by six granite pillars. These were removed in 1897, during a major addition that included remodeling the facade of the original building and expanding it north, to the right from this view. The current front entrance was added at this point, with its four pillars and the phrase “Obedience to Law is Liberty” carved above them. On the right side of the building, this section matches the design of the reconstructed 1845 building, giving the building a symmetrical Main Street facade.

The courthouse remained in use for nearly a century after the first photo was taken, but by the early 2000s it was replaced with the current courthouse several blocks south of here on Main Street. After years on the market, the building was sold to a private developer in 2015, who plans to preserve it and put it to a new use. From the exterior, not much has changed with the building itself from this angle, although some of its surroundings have. The statue in the first photo, honoring Civil War general Charles Devens, is missing in the 2016 scene, but it is still at the courthouse, having been moved just around the corner and out of view to the right.

Aside from the statue, the only other significant change is the structure in the foreground. Part of the Ernest A. Johnson Tunnel, it was built in the 1950s by prominent Norwegian civil engineer Ole Singstad, who at this point in his career has already been responsible for such projects as the Lincoln and Holland Tunnels in New York City. Substantially easier than building under the Hudson River, this project involved bypassing the congested Lincoln Square to provide a direct underground connection between Main and Salisbury Streets. It is still used today, carrying southbound traffic into downtown Worcester and merging onto Main Street just south of the old courthouse.