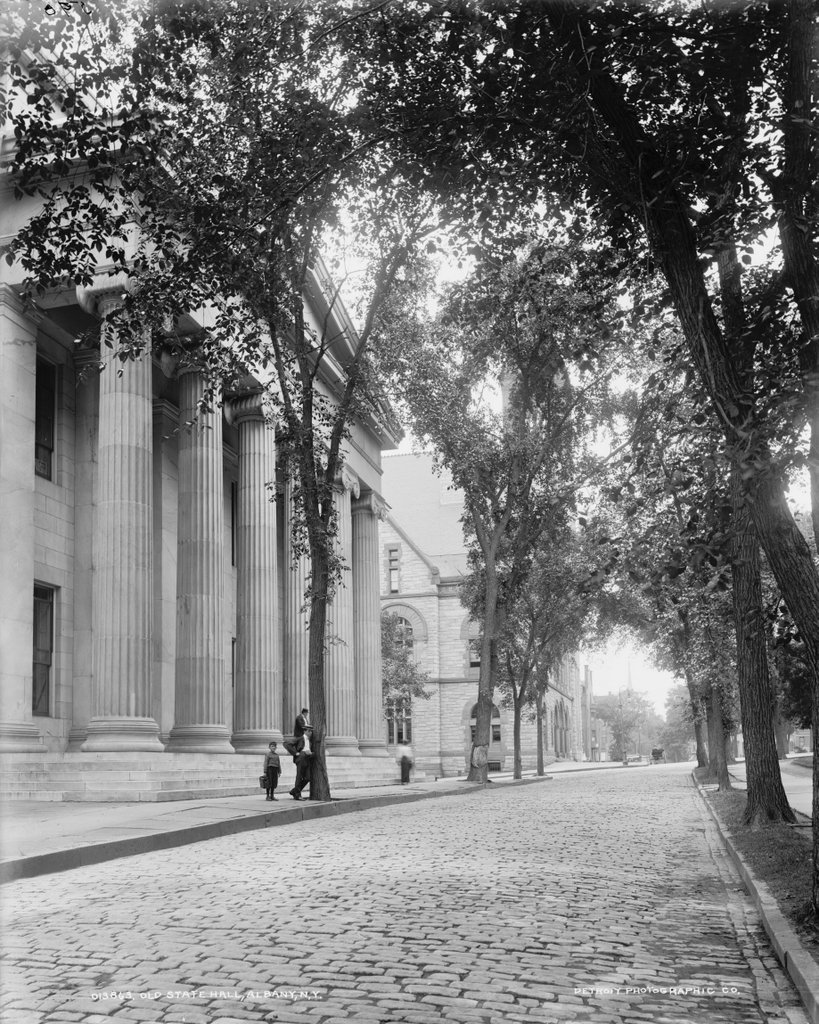

Looking south on Eagle Street in Albany, with State Hall in the foreground and City Hall further in the distance, around 1900. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

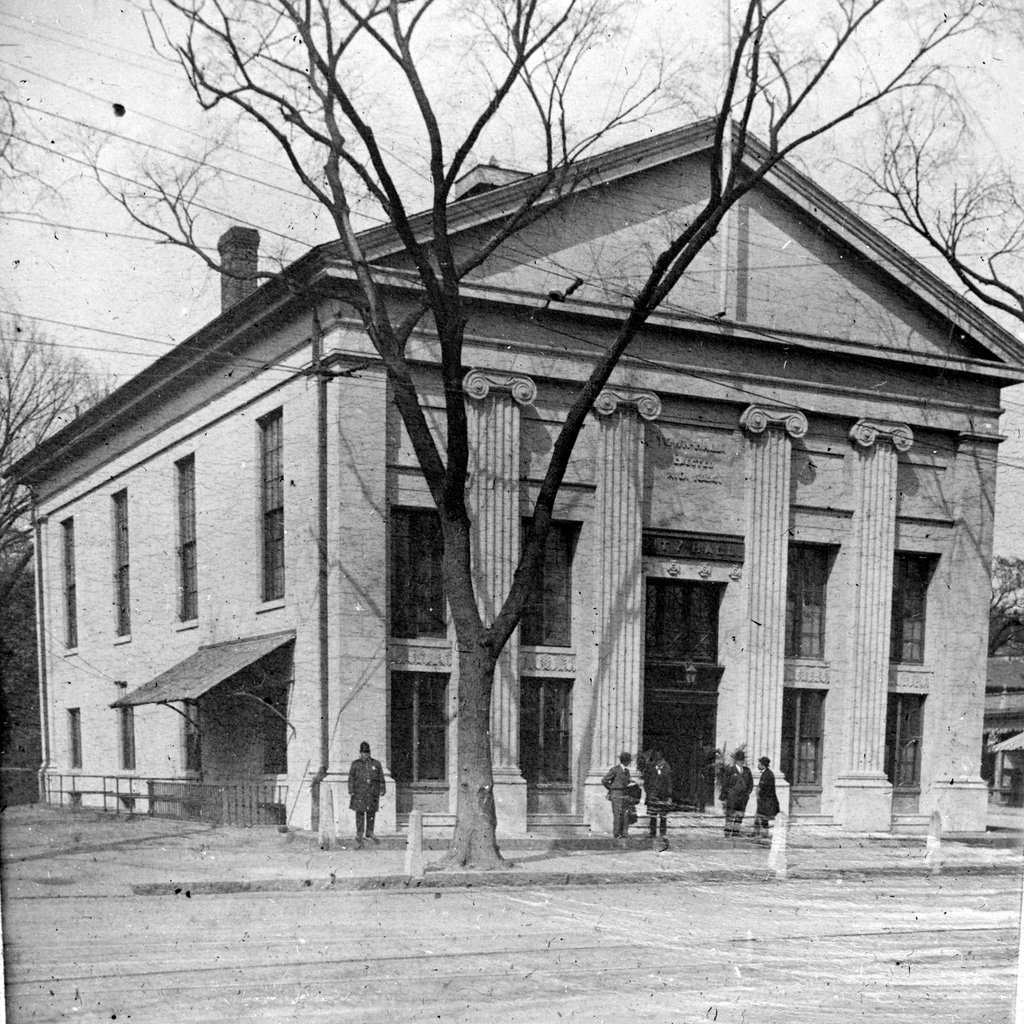

For most of the 19th century, the seat of the New York state government was the old capitol building, which was completed in 1809 and demolished in 1883. However, the capitol was too small for all of the state offices, so during the early 19th century many of these offices were located in what became known as the Old State Hall, at the corner of Lodge and State Streets. Then, in 1842, a new State Hall was built here on Eagle Street, on the left side of both of these photos.

The new building housed a variety of officials from both the executive and legislative branches. These included the secretary of state, comptroller, treasurer, attorney general, state engineer and surveyor, superintendent of the bank department, superintendent of public instruction, canal commissioners, canal appraisers, state chancellor, register of chancery, and clerk of the court of appeals.

Architecturally, State Hall was a far more imposing building than the old capitol. It was designed by architect Henry Rector, and it features a Greek Revival exterior, which was fashionable for public buildings of this era. Here at the front entrance, facing Eagle Street, is a large portico with a pediment that is supported by six large Ionic columns. Around the rest of the building, Doric pilasters are interspersed between the window bays, and the building is topped by a large dome. State Hall was also far costlier to build than the capitol, and it generally had better quality building materials, most notably an all-marble exterior, as opposed to the capitol’s relatively plain brownstone.

The old capitol was eventually demolished in 1883, after the state government moved into the current capitol building, which stands diagonally across the street from State Hall. However, State Hall remained in use throughout this time, and it was still occupied by state offices when the first photo was taken at the turn of the 20th century. By this point, it had also been joined by the current Albany City Hall, located just beyond the building in the center of both photos. This was the work of prominent architect Henry H. Richardson, who had also been involved in designing the new capitol. Its distinctive Romanesque architecture provides an interesting contrast to the Greek Revival design of State Hall, reflecting the shifts in architectural tastes over the course of the 19th century.

Although the new capitol building was much larger than its predecessor, it was still insufficient for the growing New York state government. As a result, by the early 20th century the Court of Appeals, which was located in the capitol, was looking for new space elsewhere. In New York, the Court of Appeals is actually the state’s highest court, equivalent to the Supreme Court in most other states, and the court was in need of a facility of its own. The state government explored the possibility of building a new courthouse behind the capitol on Swan Street, but instead decided upon converting State Hall into a courthouse.

Along with renovating the interior, the project also involved expanding the building with an addition to the rear, which housed the courtroom itself. The courtroom had originally been located in the capitol, where it was designed by Henry H. Richardson. However, when the Court of Appeals judges left the capitol they took the courtroom with them, and its ornate oak paneling, fireplace, and furnishings were reinstalled here in State Hall.

The project was completed in 1917, and the building was renamed Court of Appeals Hall. It has undergone several renovations since then, in the late 1950s and early 2000s, and it also suffered a large fire in 1958 that destroyed the roof and dome. However, it is still occupied by the Court of Appeals, and this view of the building has remained essentially unchanged since the first photo was taken, aside from the “Court of Appeals State of New York” inscription on the entablature. Further in the distance, City Hall is also still standing with few exterior changes, and it remains in use by the city government. Because of their historical and architectural significance, both of these buildings were added to the National Register of Historic Places in the early 1970s.