The northeast corner of Main and Bridge Streets in Springfield, Mass, around the 1860s or 1870s. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The scene in 2018:

Up until the mid-19th century, the commercial center of Springfield was along Main Street in the immediate vicinity of Court Square, where most of the important stores, banks, hotels, and other businesses were located. This began to change with the arrival of the railroad in 1839, when a railroad station opened on Main Street, about a half a mile north of Court Square. A second commercial center soon sprung up near the station, with a particular emphasis on hotels and restaurants for travelers.

By 1850, Springfield was experiencing steady growth, but its population was still under 12,000 people at the time, and the Main Street corridor in the downtown area was still not fully developed. There were plenty of businesses and large buildings clustered around Court Square and the railroad station, but the blocks in between consisted of just a few commercial buildings, interspersed by homes, churches, and vacant lots. It would not be until the city’s post-Civil War population boom that this entire section of Main Street would be lined with larger buildings.

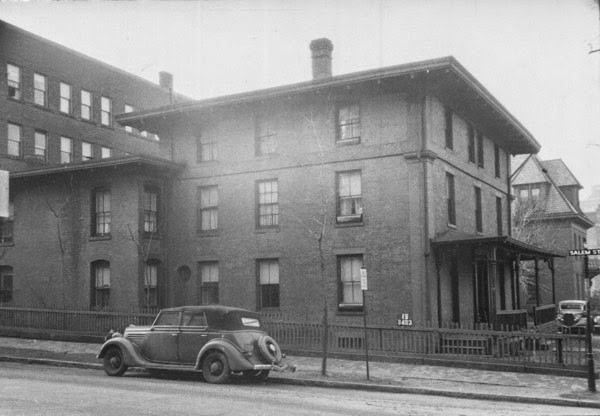

The first photo was taken sometime soon after the end of the war, and it shows a couple of the modest, wood-frame buildings that once stood along this part of Main Street. They were located at the corner of Bridge Street, about halfway between Court Square and the railroad station, and they would have been the first things that an eastbound traveler to Springfield would see on Main Street, after coming across the old covered bridge and walking up Bridge Street. Dwarfed by a massive tree – probably an elm – on the left side, these small, two-story buildings were probably constructed sometime in the 1850s. By the time the first photo was taken, they housed, from left to right, sign painter James C. Drake, wholesale cigar dealer C.H. Olcott, and stove dealer Edmund L. DeWitt.

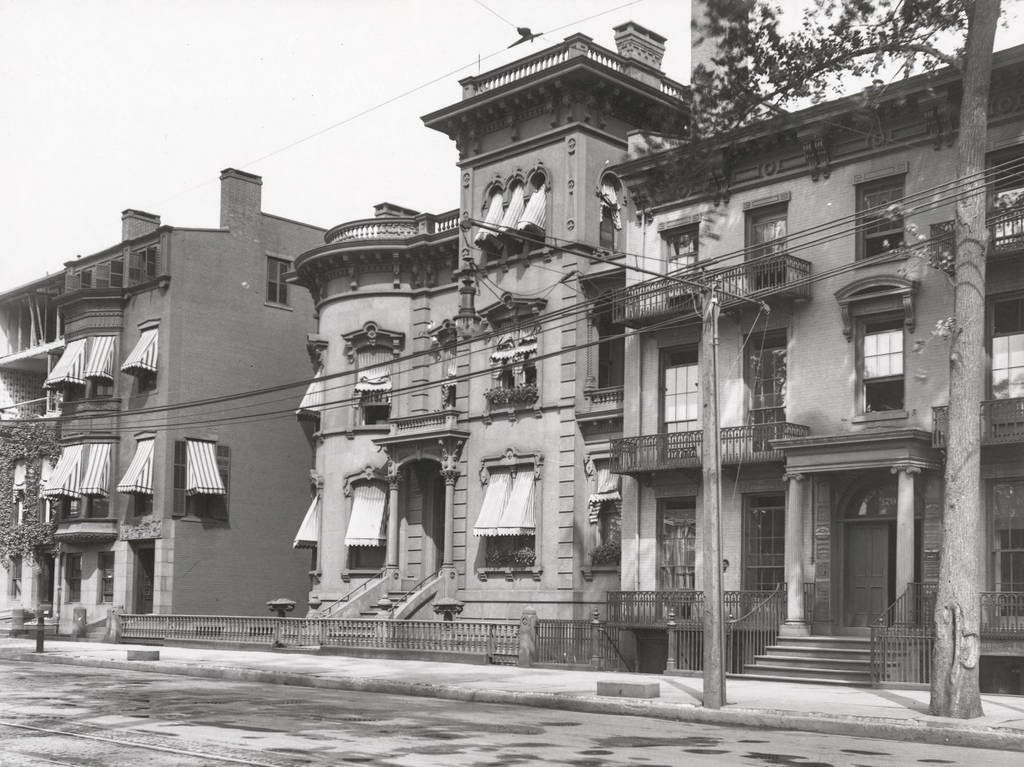

These buildings stood here until the mid-1880s, and they were probably among the last surviving wood-frame buildings on Main Street in the downtown area. However, they were demolished to make room for the Fuller Block, a large five-story brick building that was completed in 1887. Like the other new commercial blocks that were constructed in the late 19th century, it housed retail shops on the ground floor, with professional offices on the upper floors. However, it featured a unique Romanesque-style design that incorporated Moorish elements, such as the horseshoe arches above the fifth floor windows, and a large onion dome that originally sat atop the right-hand corner of the roof.

Today, some 150 years after the first photo was taken, there are no surviving landmarks except for the streets themselves. However, the Fuller Block that replaced these older buildings is still standing, and aside from the loss of the onion dome its exterior has remained well-preserved. It is one of the finest 19th century commercial blocks in the city, and in 1983 it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.