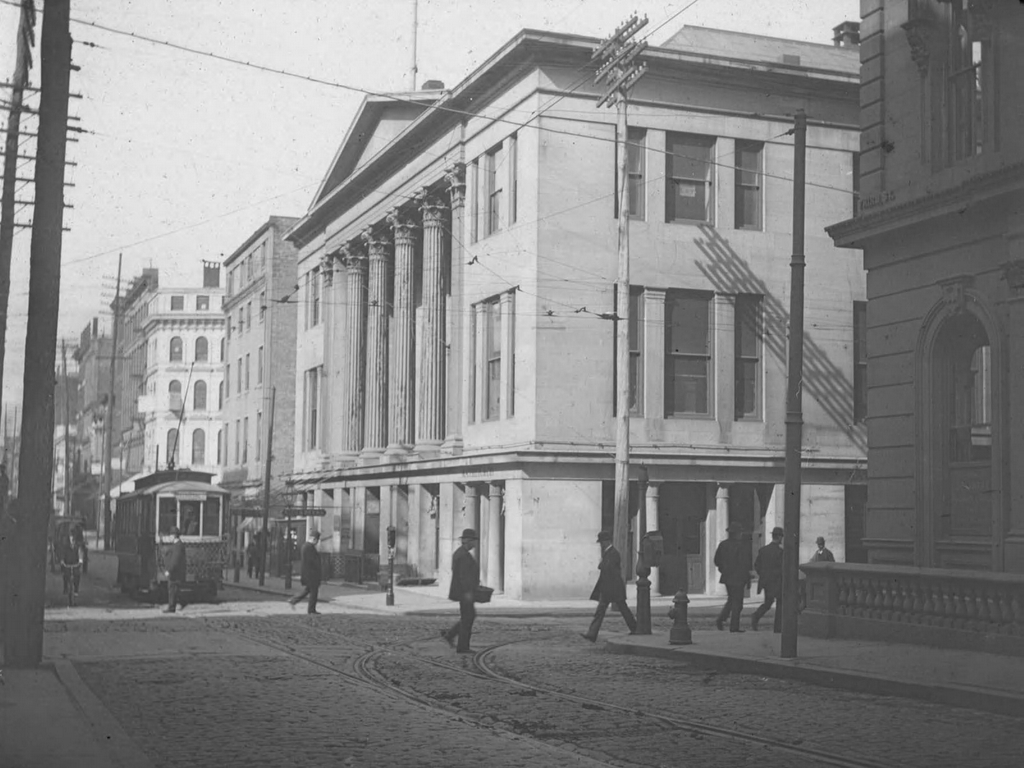

The house at 270 Liberty Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The house in 2025:

This brick Italianate-style house was built sometime around the early 1850s, and it was the home of Thomas Wason, the founder of the Wason Manufacturing Company. At the time, this area of Springfield to the east of Chestnut Street and north of the railroad tracks was sparsely developed, consisting primarily of upscale homes that were modeled on rural Italian villas. A number of these houses are visible in the first photo of an earlier post, which shows the view around 1882, before the area was transformed into the working-class Liberty Heights neighborhood at the turn of the 20th century.

Thomas Wason was born in New Hampshire in 1811, and he grew up in a family with 15 children. His father was a carpenter, so Thomas worked in the shop when he was young, and gained valuable skills that he would put to use after he and his younger brother Charles moved to Springfield in the 1830s. At the time, Springfield was a small but rapidly-growing manufacturing center, and it was also an important transportation hub that would soon become the crossroads of several important railroads.

The Wason brothers took advantage of this new method of transportation, and they started out by preparing timbers for railroad bridges and repairing railroad cars before starting a railroad car manufacturing business in 1845. The company started small, with the Wasons producing cars in a shed that was not even large enough for a single car. However, the rapid growth of the nation’s railroad system resulted in high demand for railroad cars, so the Wasons soon moved to a larger facility. Then, in 1848, they moved again, to the factory of the former Springfield Car and Engine Company, which was located in the block between Lyman and Taylor Streets in downtown Springfield.

Charles Wason ultimately left Springfield in 1851 and moved to Cleveland, where he established his own railroad car company. Thomas purchased his brother’s interest in their partnership here in Springfield, and he carried on the business for many years, turning it into one of the nation’s leading railroad car manufacturers. During that time, the Wason Manufacturing Company produced cars for most major railroads, and also had several overseas contracts, including a 161-car order that was sent to Egypt in 1860. The company also produced the nation’s first sleeping car in 1857, predating the more famous Pullman sleeping cars by several years.

The Wason company was one of the most important industries in Springfield during the second half of the 19th century, and the 1884 book King’s Handbook of Springfield declared that “no manufactory in Springfield has been more world-famed; and none has, during the past twenty years, handled so much money.” Thomas Wason himself also handled plenty of money, and by the mid-1860s he ranked among the city’s top earners, with an 1864 income of $17,944, equivalent to over $300,000 today.

Thomas Wason was around 40 years old when moved into this house in the early 1850s. He and his wife Sarah had two children, Jane and George, who would have been adolescents at the time. Like most affluent families of the period, they also employed servants who lived here in the house; the 1860 census lists 19-year-old servant Edwin Mehan, who was an Irish immigrant. A decade later, the family employed 18-year-old Annie Harris and 16-year-old Ellen Davis. Both were originally from Virginia, and Harris was listed as mulatto and Davis as black, so it is possible that the two may have previously been enslaved in Virginia.

In addition to manufacturing railroad cars, Thomas Wason’s business interests included being involved with several local banks. He was vice president of the Hampden Savings Bank, and he was also one of the directors of the First National Bank of Springfield. Wason was also active in local politics, serving at various times on the city council, the board of aldermen, and in the state legislature.

Thomas Wason died in 1870 at the age of 58, and he left behind an estate that was valued at nearly $450,000, or more than $9 million today. By far his largest asset was his ownership interest in Wason Manufacturing, which amounted to 760 shares worth a total of $200,000. He also held more than $60,000 in shares of companies like the Springfield Fire and Marine Insurance Company, the First National Bank, the Boston and Albany Railroad, and the Michigan Central Railroad. Most of his remaining personal estate was in the form of bonds and promissory notes, which were valued at more than $112,000. Wason also owned $58,500 in real estate, including his house here on Liberty Street, which was assessed at $20,000.

Sarah Wason continued to live here in this house for at least five years after her husband’s death, but she had evidently moved out by 1876. The 1880 census shows her living next door at 284 Liberty Street, at the home of her daughter Jane and son-in-law Henry S. Hyde. However, her old house here at 270 Liberty Street would remain in the family for many years, although it appears to have been used primarily as a rental property. Starting around 1877, it was the home of Aaron Wight, a sawyer who sold wood to railroads. He was also the brother of Emerson Wight, the mayor of Springfield from 1875 to 1878. Aaron lived here in this house for the rest of his life, until his death in 1885 from typhoid malaria at the age of 63.

By the late 19th century, this part of Springfield had begun to change. As the city grew, the old estates here were steadily subdivided into new residential streets, and the neighborhood became predominantly working class, with a number of immigrants and second-generation Americans. The area also became more industrialized during this period, thanks to its proximity to the railroad tracks. The 1899 city atlas shows a rail yard directly across the street from the house, and nearby industries included a stone yard, a coal yard, and a boiler and iron works.

The house was still used as a residence in 1900, although it was apparently divided into multiple units. One of the residents in that year’s census was George K. Geiger, superintendent at the Springfield Steam Power Company. He was an immigrant from Germany, and he lived here with his wife Rosa and their two sons, George and Arthur. The other family living here at the time was Hector and Nell Davis, who lived here with their children Mabel, Fred, and Eugene. Hector was a conductor for the Boston and Maine Railroad, and Mabel and Fred both worked as clerks.

This property underwent a dramatic transformation around 1909, when the Central Storage Warehouse purchased it and built a brick warehouse behind and to the right of the old house. The building evidently functioned much in the same way as modern storage units, with the company advertising, “Storage rooms to let. For furniture and other goods in separate locked compartments.” The warehouse was subsequently expanded in the early 1910s, with a new wing that extended all the way to Liberty Street, as shown on the right side of both photos here.

George Geiger was involved with the company in its early years, working as mechanical engineer and superintendent. By the 1910 census, both he and the Davis family were still living here in the house, although the Davises moved out soon after, and the Geigers left in 1912, when George resigned from his position with the company. After the Geigers, the last long-term resident of this house appears to have been Linda Daniels, who was here from around 1912 until her death in 1921. During the 1920 census she was 60 years old, widowed, and lived in the house with three of her children.

By the mid-1920s, the property seems to have been exclusively commercial in use. During this period, the company frequently listed advertisements in local newspapers, which reflected an expansion of its services beyond just storage. One 1925 ad offered “Local and long distance moving, packing, crating, storage of household furniture, pianos, office effects, merchandise.” Another ad from the same year assured potential customers, “Don’t worry on moving day. Call R. 98 and your moving problems will be solved to your complete satisfaction; storage for household, personal and office effects in strictly fireproof building; skilled workmen, competent to pack and crate any article safely.” In addition to these ads, the company also frequently posted classified ads for auctions and other sales of furniture, antiques, and similar items.

Judging by the few advertisements that appeared in the newspaper for Central Storage Warehouse in the 1930s, the business was probably hurt by the Great Depression. The first photo was taken during this time, probably around 1938 or 1939, and the company’s only appearance in the newspapers in those years seems to have been a December 1939 classified ad listing female canaries for sale, which were “guaranteed singers.”

The company remained here as late as 1940, but its business license was revoked in the fall of that year, and in February 1941 the property was sold at a foreclosure sale to the moving and storage company Lindell & Benson. Within a few years Lindell & Benson became Anderson & Benson, and this moving company would go on to operate here for many years before it was acquired by Sitterly Movers in 1975.

Today, the house has come a long way since being the home of one of Springfield’s most prosperous 19th century industrialists, and it has seen some exterior changes since the first photo was taken, including the loss of the porches on the left and right sides of the house. Despite the exterior alterations, though, the house is still standing as one of the few survivors of the once-numerous Italian villas in this area. The early 20th century warehouse next to it is also still standing, with the same “Furniture Storage” advertisement still visible at the top, although it is more faded than in the 1930s. This property is still owned by Sitterly Movers, which continues to use this location as its Springfield branch, and in 2016 both buildings were designated as a local historic district.