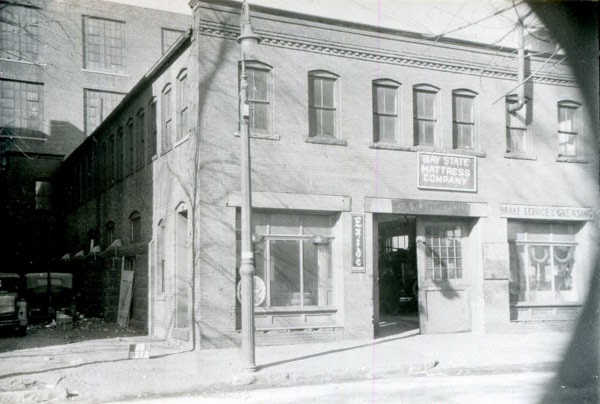

The factory of Bemis & Call Hardware and Tool Company at 125 Main Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The scene in 2017:

The origins of the Bemis & Call Hardware and Tool Company started in the 1830s, when merchant Stephen C. Bemis began manufacturing hardware here in Springfield. One of his early business moves was to purchase Solyman Merrick’s patent of the monkey wrench, which would become one of the company’s leading products. He subsequently formed a partnership with Amos Call, and in the 1840s Bemis & Call began manufacturing tools and hardware in a factory here on this site along the Mill River. The company initially rented space in a factory building that they shared with several other tenants, but later in the 19th century they would purchase the entire site.

Stephen C. Bemis retired from the company in 1855, and went on to have a career in politics. He served as a city alderman from 1856 to 1858, as mayor in 1861 and 1862, and in between he was the Democratic nominee for lieutenant governor in 1859, although he lost the general election to fellow Springfield politician Eliphalet Trask. In the meantime, his son, William C. Bemis, became treasurer when Stephen retired, and remained with the company for the next half century.

William became president in 1897, and that same year the company built a large addition to the original factory. This three-story brick building, seen in the center of both photos, was joined four years later by the more ornate two-story section on the right, which was used as the company’s offices. The original wooden building stood on the left side until around 1920, when it was demolished and replaced with the current four-story brick building. During this time, Bemis & Call continued to specialize in wrenches, but also produced punches, pliers, calipers, and eventually combination locks.

Bemis & Call finally sold their wrench line in 1939, around the same time that the first photo was taken. However, unlike so many other Springfield-based companies, they survived the Great Depression and remained in business until finally closing in 1988. The factory buildings themselves are still standing, though, with hardly any exterior changes since the first photo was taken nearly 80 years ago, and they serve as a reminder of Springfield’s legacy as an important industrial city in the 19th and early 20th centuries.