The Pavilion on State Street in Montpelier, around 1904. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2019:

Throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, one of the major landmarks in Montpelier was the Pavilion Hotel, which stood on the north side of State Street, just east of the Vermont State House. The original Pavilion was built in 1808, the same year that the first state house was built next door. At the time, Montpelier had just recently been designated as the capital of Vermont, and it was still a small town, with under 900 residents during the 1800 census. As a result, the Pavilion was built, in part, to meet the anticipated need for accommodations, especially during legislative sessions. Over time, the hotel would come to be closely identified with the state government, and despite being privately owned it was unofficially regarded as the “third house” of the legislature.

The first Pavilion Hotel stood here until 1875, when it was demolished to build a new, larger Pavilion. Work on the new hotel began with the groundbreaking on February 22, 1875, and it opened for guests exactly 11 months later, on January 22, 1876. The formal dedication ball occurred a month later, on February 22, and it was attended by over 250 couples. The event lasted well into the night, and did not wrap up until 6:00 the following morning.

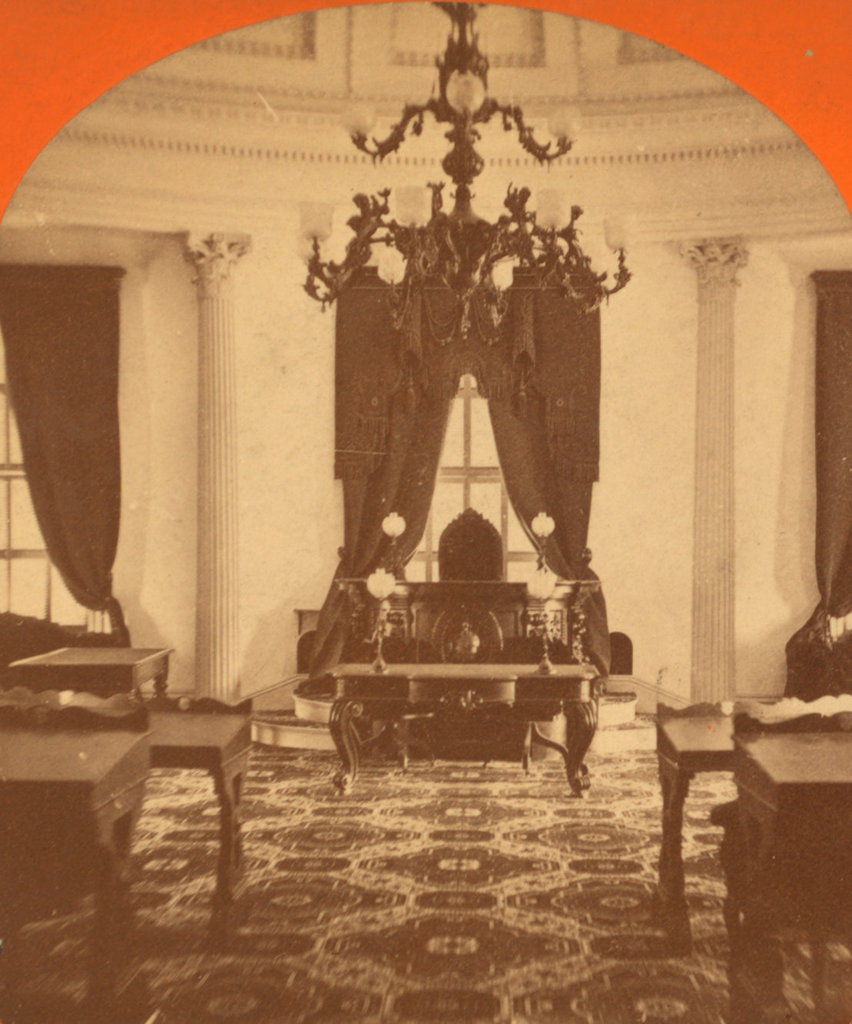

Upon completion, the new hotel consisted of four floors, with a low roof atop the building; the fifth floor with its Mansard roof would not be added until 1888. The main entrance was located here on the State Street side of the building, with the ladies’ entrance on the left side facing the state house. The first floor of the building featured the hotel offices, along with a reception room, reading room, two dining rooms, the kitchen, and some of the guest rooms. On the second floor there were more guest rooms, along with three parlors and the hotel proprietor’s living quarters, and the two upper floors were entirely comprised of guest rooms. In total, the hotel had 90 guest bedrooms. The basement was primarily utility space, but it also included a billiards room and barber shop.

The first photo was taken around the turn of the 20th century, after the 1888 expansion that added 35 guest rooms to the building. At the time, the hotel was still popular among Vermont legislators, and it also enjoyed steady business from tourists who sought the relatively quiet, rural setting of Montpelier. According to a 1906 advertisement in a travel guide, rooms cost $2 per night, or about $58 in today’s dollars, which made it the most expensive of the three Montpelier hotels that had prices listed.

By mid-century, though, these trends had changed. Across the country, historic downtown hotels were suffering from declining business, and the Pavilion was no exception. The explosion of car owner0hips, along with the Interstate Highway System, made it easier for travelers to stay at convenient new motels right off the highway, rather than driving into a downtown area and trying to find parking in order to stay at an aging hotel. Here in Montpelier, this was compounded by the fact that many legislators no longer needed to stay overnight in the city during legislative sessions. With travel times drastically reduced, commuting became a more attractive option for those who lived within easy driving distance of the capital.

As a result, the Pavilion declined to the point where it was in poor repair, and was generally seen as a low-budget alternative to newer motels. In the meantime, the state became interested in acquiring the property, given its highly visible location next to the state house. The state ultimately purchased it in 1966, and the hotel closed for good later in the year.

Over the next five years, the building became the topic of debate between state officials who wanted to demolish the old hotel and construct a new state office building, and preservationists who wanted to see the historic building renovated into offices. The reasoning behind the demolition was that it would cost more to renovate the building than to construct a new one. In the end, the state struck a sort of compromise that involved demolishing the hotel and constructing an exact replica on the same spot. This maintained the visual effect from the street, but it was hardly a win for preservationists, who argued that complete demolition could in no way be considered a type of historic preservation.

The building was demolished during the winter of 1969-1970, and the replica state office building was completed in early 1971. Among the occupants of the new building was the governor. The formal governor’s office remained in the state house, and continues to be used during legislative sessions, but the governor’s working office has been in the new Pavilion ever since. Initially, the governor’s office was located on the fifth floor, in the corner on the right side of the building, but it was subsequently relocated to a modernist addition, located in the rear of the building.

Today, these two photos give the appearance that very little has changed, although in reality there is almost nothing left from the first photo. Aside from a few pieces of the old Pavilion façade that were incorporated into the new one, the only survivor in this scene is the former offices of the Vermont Mutual Insurance Company, the corner of which is visible on the right side of the first photo. Although it is not shown in the 2019 photo, it is still standing today, and it is now used as offices for the state’s attorney and the sheriff’s department. The other government building visible in this scene is the one on the far left of the 2019 photo, which was completed in 1918 and houses the state library and the state supreme court.