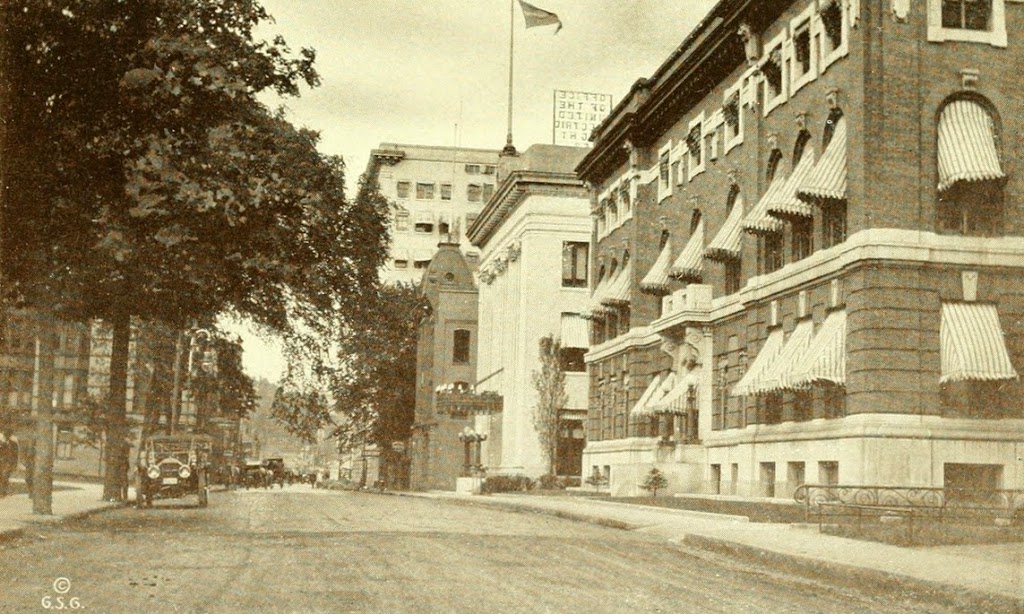

President William Howard Taft, giving a speech on Court Square in Springfield, on April 25, 1912. Photo from Progressive Springfield, Massachusetts (1913).

The scene in 2014:

The 1912 photo was taken on the same day as the photo in this post, which shows a close-up of President Taft speaking on the platform. Here, the platform can be seen behind Old First Church on the left-hand side, and it shows the massive crowd that had assembled to see him during his 1912 presidential campaign, which would end with him earning the Republican nomination but losing to Woodrow Wilson in the November election. Today, three of the buildings from the first photo are still there: Old First Church, the Court Square Hotel, and the old Hampden County Courthouse. There are also some remnants of this part of Court Square, which once stretched from the back of Old First Church to the Connecticut River (which can be seen in this post). Today, the Hampden County Hall of Justice covers part of the land, and East Columbus Avenue passes diagonally across it.