An early 20th century postcard showing the view looking east along the Boston and Albany Railroad, with a stone arch bridge on the left side and the Westfield River on the right. Image from author’s collection.

The scene in 2021:

The first railroads in the United States were constructed starting in the late 1820s. These were mostly concentrated in the northeast, and they tended to be relatively short lines that linked neighboring cities. Here in New England, Boston soon emerged as an important railroad hub, and by the mid-1830s it had three different lines that radiated outward as far as Lowell, Providence, and Worcester. However, railroad investors had far more ambitious plans, including one proposal that would extended the line west of Worcester all the way to Albany.

Throughout the colonial era, and into the early 19th century, Boston had been one of the most important seaports in the present-day United States. However, as settlers moved west, and as the country acquired new territory, Boston found itself on the far eastern edge of a nation that was rapidly expanding westward. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 further threatened Boston by linking New York City with the Midwest, making it the primary seaport for trade with the inland regions.

As early as 1826, the Massachusetts state legislature had begun exploring the possibility of a railroad from Albany to Boston. This would prevent Boston from becoming economically isolated from the rest of the country, by providing an alternate route to the sea for goods transported along the Erie Canal. The state subsequently hired prominent civil engineer James F. Baldwin to examine potential routes through the state. The most promising was a southerly route, which would head west from Worcester through Springfield and Pittsfield before crossing into New York. This is, more or less, the route that would ultimately be opened a little over a decade later.

To achieve this goal, the Western Railroad was incorporated in 1833, although construction work did not start until 1837. The eastern half of the railroad, from Worcester to Springfield, was relatively easy to build, and it opened on October 1, 1839. However, the western portion, which crossed the mountains of the Berkshires, was a far more challenging engineering feat. By this point, railroad technology was still in its infancy, and there were still significant questions about the ability of steam locomotives to operate on steep grades. Some doubted whether a locomotive could handle grades greater than one percent (one foot of vertical rise for every hundred feet of track), and many early railroads used steam-powered inclined planes to pull trains up steep sections of the route. However, any crossing of the Berkshires would require consistent grades in excess of one percent, in some places even exceeding 1.5 percent.

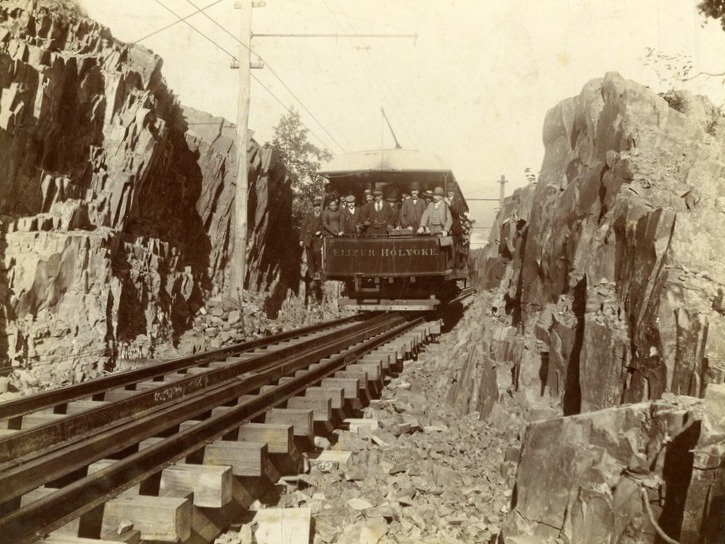

To reach the divide between the Connecticut River and Housatonic River watersheds, the route of the railroad followed the Westfield River to the west of Springfield. In the town of Huntington, the river splits into three main branches, with the railroad continuing upstream along the west branch. From there, the river valley becomes increasingly narrow and winding, particularly in the last 13 miles from Chester to the watershed divide in Washington.

In order to oversee this project, the railroad hired George Washington Whistler as chief engineer. An 1819 graduate of West Point, Whistler was one of the nation’s leading civil engineers, and he was involved in the construction of many early railroads. He would go on to earn international fame from his accomplishments here on the Western Railroad, and Czar Nicholas I of Russia subsequently hired him to build the Saint Petersburg–Moscow Railway. However, Whistler’s fame would ultimately be eclipsed by his son, the prominent artist James Abbott McNeill Whistler, who was a young child living with his family in Springfield when George Washington Whistler built the Western Railroad.

For Whistler, the most difficult part of the project would be the 13 miles between Chester and Washington, where the railroad rose in elevation from 600 feet in Chester to 1,459 feet at the watershed divide. This was a serious challenge, given the concerns about the technical limitations of steam locomotives, but Whistler also had to build this railroad within the confines of a narrow, sinuous river gorge. This meant the railroad would require a series of deep rock cuts and high embankments, along with repeated crossings of the river, in order to maintain a reasonable grade. Even so, the finished railroad would have a six-mile section with an average grade of 1.51 percent, and a maximum grade of 1.57 percent.

Probably the most distinctive feature of this section of the railroad is its many bridges. The railroad crossed the river a total of 21 times in these 13 miles, and ten of these bridges were masonry arch bridges, including the one shown here in these two photos. The original intent had been to use simpler bridges with rubble masonry abutments, but these would have been vulnerable to spring flooding, so the railroad opted for more substantial arch bridges. This required excavating down to bedrock to anchor the abutments, and it also meant bringing in quarried stone from elsewhere, since the local stone proved to be of inferior quality. This was a significant expense for the railroad, as these quarried blocks—which weighed upwards of a thousand pounds each—had to be transported along rough roads to these remote work sites along the river.

Aside from the bridges, other labor-intensive work included the many cuts and fills along the railroad bed. A little to the east of the bridge in this photo, just beyond the curve in the distance, is a deep rock cut, measuring about 575 feet long and 30 to 40 feet deep. In the days before dynamite and other high explosives, this work would have been done using only black powder and hand tools such as picks and shovels. Beyond this rock cut was an embankment, with a long stone retaining wall that had to be built to keep the railroad bed from sliding off the steep cliff down to the river. A few miles to the west of the stone bridges, at the highest point of the railroad in the town of Washington, was an even larger rock cut. It was about a half mile long, and 55 feet deep at its deepest point.

All of this work, including the unanticipated need for stone arch bridges, led to significant cost overruns for the Western Railroad. In 1838, prior to the start of construction, the cost of building section of the railroad to the west of the Connecticut River was estimated at $2.1 million. The actual cost turned out to be a little over $2.5 million, including nearly $1 million just to build a 13-mile section here in the Berkshires. The single most expensive mile was just a little to the east of the scene in these photos, between mile markers 127 and 128. Within that mile, the railroad crossed the river three times on large stone arch bridges, and cost nearly $220,000. The company’s January 1841 annual report explained some of the reasons for these added expenses, quoting the engineer (presumably Whistler), who wrote about the challenges of building the railroad through this section along the Westfield River:

With the limited knowledge of the character of the stream here, at the time of the original estimate, and, judging of its effects in times of freshets, from the comparatively unstable character of the structures then existing on the turnpike, occupying almost the immediate line of the rail-road, in tolerable security, it was then judged that structures of the more ordinary kind, with common rubble masonry for bridge abutments and side walls, would give ample security to the road, and such was estimated for. But the experience in time of our personal knowledge of the effects of freshets in this stream, proved the necessity of abandoning such structures, and resorting to others of a more costly and permanent character. Stone arches of large openings were adopted, requiring masonry of a very different and superior character to support them;—rendering it necessary too to resort to great depths in search of permanent rock foundations below the bed of the stream. This was the more readily acceded to at the time, from the belief (as every appearance indicated) that materials suitable for such structures would be obtained from the rock cuts in their immediate vicinity. But soon after they were commenced, and the character of the stone exposed by the opening of the cuts, it proved entirely unfit; and the contractor was compelled to resort to quarrying and hauling the stone from a distance, and over roads almost impassible;—thus rendering it necessary to increase his prices to meet this additional cost.

The work of actually building the railroad was largely done by immigrant laborers, primarily the Irish. At one point there were several thousand workers employed here, and this is evident in the 1840 census, which was conducted in the midst of the railroad construction. In a sort of precursor to the later railroad boom towns that would follow the First Transcontinental Railroad several decades later, the town of Middlefield—located on the north side of the river—saw a particularly dramatic increase in population. From a population of 720 in 1830, Middlefield grew to 1,717 in 1840, with the census noting that 686 were from “Middlefield proper,” while the rest were counted as “extraneous population.”

These workers generally lived in temporary shantytowns along the river, and the census indicates that most were in their 20s or 30s, with few over the age of 40. The 1840 census does not provide much specific demographic information, and only the heads of the households are individually named, but the census data suggests that most of these men lived here with their families. Most of the households included both a man and a woman who were between the ages of 20 and 40, along with several young children who were generally under the age of 10. The surnames of the heads of household were overwhelmingly Irish, with Murphy being a particularly common name among the workers in Middlefield.

The arrival of so many foreign immigrants in a small, rural community was not without controversy. Early in the construction process, in the spring of 1839, the Hampshire Gazette published an article titled, “The Irish on our Public Works,” which addressed concerns about the societal impact of the Irish immigrants who were working on the railroad. The article warned that, “[i]f some measures are not taken for the education and moral reformation of the multitudes of Irish and other foreign emigrants that swarm the country, our republic will be much in danger from them.” Perhaps in response to these concerns, a few months later a resident of Middlefield began raising funds to establish three schools for the children of the laborers. It seems unclear as to whether these contributions were motivated by genuine altruism or by nativist fears about an under-educated immigrant class, but a subsequent article in the Boston Evening Transcript declared that the students were “learning rapidly, and doing credit to the labors of their benefactors.”

These workers remained here throughout the summer of 1841, and the railroad was ultimately completed in the early fall, with the final tracks laid at the rock cut in Washington on October 2, 1841. The railroad opened two days later, linking Boston and Albany. In the process, the railroad set a number of records. It was, up to that point, the longest and most expensive railroad in America, and it was also the first to be built through mountains without using steam-powered inclined planes to assist locomotives. As such, it was a significant engineering milestone, and it was enough to gain the attention of the czar, who brought Whistler to Russia as soon as his work here on the Western Railroad was finished.

However, despite the completion of the railroad, there would continue to be challenges, including a fatal accident that occurred on October 5, 1841, just a day after the line opened. The railroad originally just had one track, with occasional passing sidings for trains heading in opposite directions, including ones at Chester and Westfield. On this particular day, both the eastbound and westbound trains were given instructions to meet at Chester before proceeding. However, the eastbound conductor apparently never received this message, and was expecting to meet the other train further down the line in Westfield. This resulted in a head-on collision about four miles west of Westfield, killing the conductor of the eastbound train and one passenger, along with injuring many others. The accident was a personal tragedy for George Washington Whistler, whose niece, Caroline Bloodgood, was on the train. She was among those injured, and her young son was the one passenger who was killed in the accident.

The Western Railroad did manage to help dispel the myth that steam locomotives were unable to ascend steep grades under their own power, but the section of the railroad here in the Berkshires was nonetheless challenging for trains. Whistler had selected locomotives that were built by Ross Winans of Baltimore, a friend of his whose daughter Julia would later marry his son George. Nicknamed “crabs,” presumably because of their eight drive wheels and Maryland origins, these locomotives proved unreliable here on the Western Railroad, and the railroad ultimately resorted to custom building their own mountain locomotives at their shops in Springfield.

Despite these setbacks, the railroad overall proved to be a success, and for many years it was the only east-west railroad through the Berkshires, providing an important transportation link between Boston and the rest of the country. Although it was originally built as a single-track railroad, Whistler had wisely designed the bridges and other structures to accommodate a second track. This made the initial construction costs higher, but in the long run it saved the railroad money by making it easy to add a second track without having to reconstruct all of the bridges.

For travelers along the route, this section through the Berkshires was a highlight of their journey. The 1847 travel guide A Chart and Description of the Boston and Worcester and Western Railroads, published only six years after the railroad opened, provides the following description:

No language that we are master of could give the traveller any proper description of the wildness, the grandeur, or the obstacles surmounted in the construction of this portion of the route. The river is exceedingly crooked, and the lofty mountains, which are very steep and rugged, and of solid rock, shut down quite to the river on both sides, their sharp points shooting by each other, rendering crossings at every bend of the stream indispensable. In addition to this, the points of the hills must be cut away, and for many miles these rock cuttings and bridges follow each other in regular and rapid succession. . . . Nor does the passing traveller, hurling along as rapidly as he is, see much of the beauty of this mountain gorge. It is not until he has seen, from the base of these mighty structures of art, the passage of the cars, that their magnificence is really felt.

The Western Railroad would ultimately merge with the Boston and Worcester in 1867, forming the Boston and Albany Railroad. This company would, in turn, be leased by the New York Central starting in 1900, although this line retained the Boston and Albany name well into the 20th century. In the meantime, the railroad continued to make improvements to the route, including some changes here along the banks of the Westfield River. A few of the original bridges were replaced, including the easternmost one, which was replaced in 1866 with the current double arch bridge. The next bridge upstream from there was replaced in 1912 with the current steel deck truss girder bridge, although the original stone abutments appear to still be there, encased in poured concrete. Much further upstream, the westernmost two bridges were apparently reconstructed in 1928 after having been damaged in a flood, although it is possible that portions of the original bridges are still underneath the concrete.

However, the most significant change to this portion of the railroad occurred in 1912, when about a mile of the railroad was rerouted, including the section shown here in these two photos. The first photo was probably taken only a few years before this occurred. The postcard is undated, and does not have a postmark, but it has an undivided back, suggesting that it was printed before 1907. As part of this realignment, the railroad shifted to the south side of the river, eliminating two of the river crossings. One of the original bridges, located about 300 yards west of here, was demolished as part of this project, in order to make room for a new bridge. Three other original bridges were simply abandoned, including this one here, which is the westernmost of the three.

Today, more than a century after the railroad was rerouted, these three bridges are still standing. One of them, the easternmost, is still on land owned by the railroad, and it is directly adjacent to the active rail line, so it is not accessible to the public. However, the other two bridges, along with the 3,000-foot section of abandoned railroad right-of-way between them, are now owned by the state as part of the Walnut Hill Wildlife Management Area. The bridges are accessible by way of the Keystone Arch Bridge Trail, a 2.5-mile long trail that starts in Chester. Despite being over 180 years old, and despite not having been maintained in well over 100 years, these bridges remain in good condition, clearly fulfilling Whistler’s goal of creating bridges of “a more costly and permanent character.”

As the travel guide had indicated back in 1847, it is hard to get a sense of the scale of these bridges from the railroad. Even today, it is hard for visitors to tell just how big these bridges are while standing atop them, and photographs are likewise unable to capture the full scope of these structures. Only by climbing down to the river and looking up at the arches can a visitor fully appreciate the size of the bridges, and the work that went in to building them in the middle of a river gorge in one of the most remote areas of the state.

Of the three surviving bridges, the one here in this scene is the largest. Including the wingwalls, the structure of the bridge is over 500 feet long, the bridge deck is about 25 feet wide, and the top of the bridge rises about 75 feet above the river. The bottom of the arch is about 60 feet above the water, and the total span of the arch is 54 feet. The bridge is mostly in its original condition, although about three-quarters of the parapet stones are gone, having apparently been pushed over the edge by vandals over the years.

In 1980, this bridge was added to the National Register of Historic Places as a contributing structure in the Middlefield–Becket Stone Arch Railroad Bridge District. Then, in 2021, the two surviving stone arch bridges on public property, including this one, were designated as National Historic Landmarks as part of the Western Railroad Stone Arch Bridges and Chester Factory Village Depot district. The district is also comprised of the railroad bed in between the two bridges, including the large rock cut and stone retaining wall, along with the historic railroad station in the center of Chester, several miles to the east of here. This station is owned by the Chester Railway Station and Museum, which features an extensive collection of artifacts relating to the Western Railroad and the construction of these bridges.

For more information on the history of these bridges, the National Historic Landmark Nomination Form is an excellent resource. The Friends of the Keystone Arches also has an excellent website, with plenty of historical information and photographs, along with information about hiking to the bridges.