The view looking toward home plate from the right field grandstands in Fenway Park, on September 28, 1914. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Bain Collection.

The scene in 2024:

These two photos were taken from close to the same spot, although the top one was likely taken a little closer to home plate. Either way, they both show the infield area of Fenway Park from the right field grandstands, and they show the many changes that have occurred here over the years.

The origins of the Boston Red Sox date back to 1901, although the team would not acquire its Red Sox name until 1908. For the first 11 years, the team played at Huntington Avenue Grounds, located on the modern-day campus of Northeastern University. It was there that the team won the first World Series, in 1903, and the Red Sox played there until the end of the 1911 season.

Fenway Park was constructed the following winter, and it opened on April 20, 1912. In that game, the Red Sox played the New York Highlanders—the future Yankees—and defeated them by a score of 7 to 6 in 11 innings. The Red Sox would go on to win the American League pennant that year, and defeated the New York Giants to win the World Series.

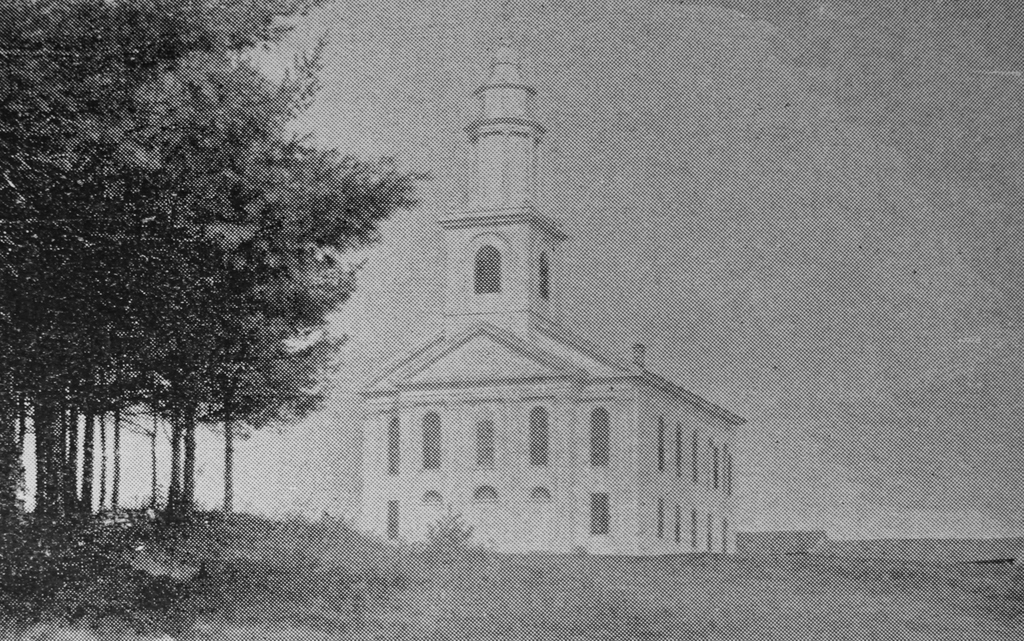

The top photo shows the grandstands and home plate area two years later, on September 28, 1914. At the time, preparations were underway to host another World Series here, but this time it wasn’t for the Red Sox. Instead, it was for the Boston Braves, the city’s original Major League Baseball team. The team played in the National League, where they had been one of the most dominant teams in baseball during the 19th century. However, with the establishment of the rival American League in 1901, the new Boston quickly eclipsed the older National League team in popularity.

Going into the 1914 season, the Braves had not been contenders in many years. The team had finished in last place for four consecutive seasons from 1909 to 1912, and they appeared to be headed for the same fate in 1914. By July 4, the Braves were in last place with a 26-40 record, and were 15 games behind first place. However, the “Miracle Braves,” as they came to be known, then went on to win 68 of the remaining 87 games in the season, and finished in first place, 10.5 games ahead of the second place Giants.

Throughout most of the 1914 season, the Braves played their home games at the South End Grounds. However, by September they were renting Fenway Park, in order to accommodate the larger crowds who came to watch their dramatic reversal and pennant run. Likewise, the Braves played their home games here at Fenway Park during the World Series, which they won in four games against the Philadelphia Athletics.

The following year, the Braves moved into a new park, Braves Field. However, it was the Red Sox who went to the World Series in 1915 and again in 1916, and they chose to play their home games at the larger Braves Field, rather than here at Fenway Park. But, the World Series would return to Fenway two years later in 1918, when the Red Sox played their home games here rather than at Braves Field. This would famously prove to be the final World Series championship for the Red Sox for the next 86 years, before their championship in 2004.

Overall, the 1910s were a successful time for the Red Sox, who won the World Series four times in the decade. Prominent players who played here at Fenway Park during this time included Hall of Famers such as Babe Ruth, Harry Hooper, Herb Pennock, and Tris Speaker. Other notable players included pitcher Smoky Joe Wood, catcher Bill Carrigan, third baseman Larry Gardner, and left fielder Duffy Lewis, the namesake of “Duffy’s Cliff,” an embankment that was once located on what is now the site of the Green Monster.

Despite the success of the 1910s, it was followed by a decade of abysmal seasons during the 1920s, due in large part to the sale of Babe Ruth and other top players to the Yankees. The team continued to use Fenway Park during this time, but in 1926 a fire destroyed the wooden left field bleachers, which are partially visible on the far right side of the 1914 photo. The owners did not have the financial ability to rebuild the bleachers, nor was there much demand for the seating with such paltry attendance figures, so that part of Fenway Park remained vacant for the next few years.

The most dramatic changes to Fenway Park occurred in 1934, shortly after businessman Tom Yawkey purchased the team. He had much of the park rebuilt, including replacing the wooden sections with fireproof concrete and steel. Most of the modern-day park dates to this renovation, including the Green Monster wall in left field. The field dimensions also changed, and home plate was moved forward to accommodate more seating. Then, in 1947 the light towers were added to the park, enabling the Red Sox to play night games here for the first time.

Over the years, Fenway Park has continued to evolve. Later changes here in this scene included work in the 1980s to increase the park’s seating capacity. Most significantly, this included adding seating areas and luxury boxes on the grandstand roof, along with a large press box and an enclosed seating area directly behind home plate. Known as the 600 Club and later as the .406 club, this seating area was eventually remodeled after the 2005 season, and it now has two separate seating areas without any glass between the seats and the field.

Today, Fenway Park is still the home of the Red Sox, and it stands as the oldest active Major League Baseball field. Although much of it has been altered over the years, it still has largely the same layout, including the field dimensions and the footprints of the grandstands and bleachers. Portions of the park are original to 1912, including the exterior along Jersey Street, and the park was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2012, during its centennial year.