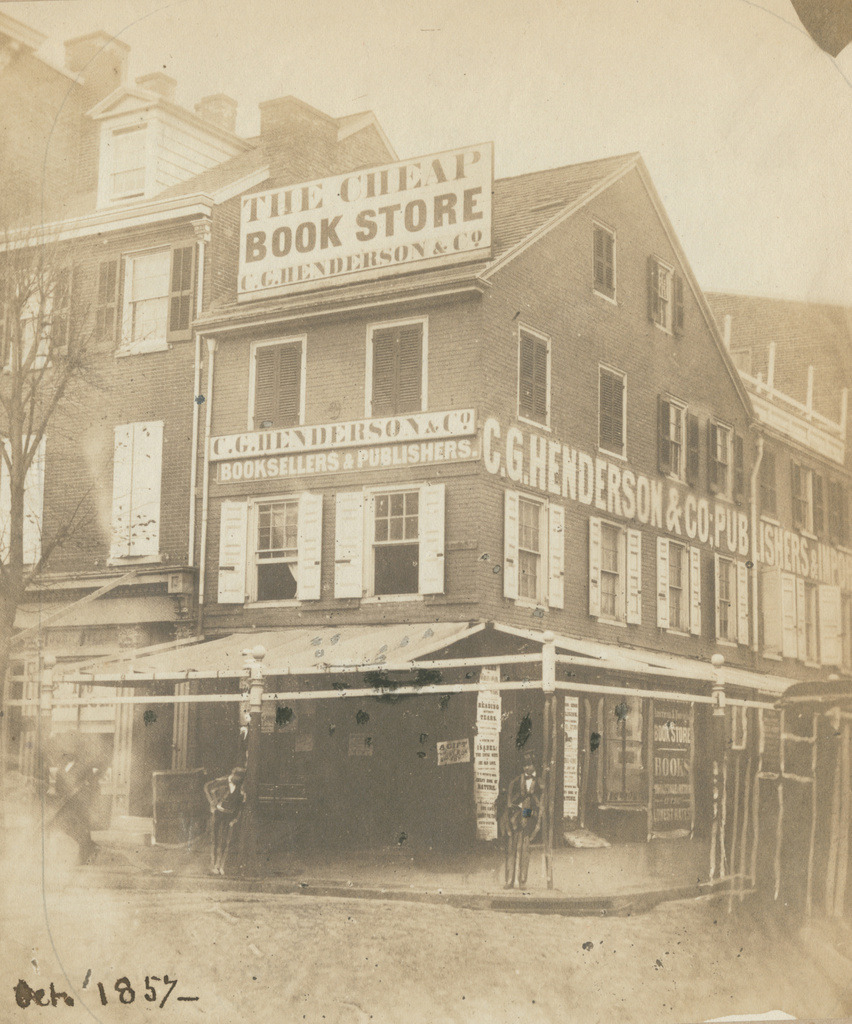

Library Hall, on Fifth Street near Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, in February 1859. Image courtesy of the Library Company of Philadelphia, Frederick De Bourg Richards Collection.

The scene in 2019:

The Library Company of Philadelphia was established in 1731 by Benjamin Franklin as the first lending library in the present-day United States. At the time, free municipally-supported libraries were still more than a century in the future, but Franklin’s library functioned as a sort of quasi-public library, making books available to subscribing members. These types of subscription libraries would become common in America in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and the Library Company of Philadelphia served as a model for many of these.

During its early years, the library did not have a permanent home. Instead, it was successively located in several different rented spaces, including the second floor of Carpenters’ Hall, which was occupied by the library starting in 1773. However, the library wanted a building of its own, a move that Franklin himself encouraged. So, in 1789 the library solicited designs for a new building, stipulating that it should measure 70 feet by 48 feet, and be two stories in height. The winning entry came from a rather unlikely source in William Thornton, a physician who had no architectural training and had never before designed a building. This would not be the only such competition that he would win, though. Four years later, George Washington selected his design for the U.S. Capitol building in Washington, D.C.

The new building, known as Library Hall, was built here on the east side of Fifth Street, a little south of Chestnut Street. This was an important location, as it was less than a block away from both Independence Hall, where the state legislature met, and Congress Hall, which would serve as the national capitol from 1790 to 1800. Construction began on Library Hall in 1789, and the cornerstone was laid on August 31. The stone featured an inscription written by Benjamin Franklin, who was still alive more than 50 years after he established the library. However, he would not live to see the building completed; he died on April 17, 1790, and the library moved into it around October. Two years later, the library added a marble statue of Franklin, which was installed in the niche above the front entrance.

The building’s completion occurred around the same time that the national government returned to Philadelphia, after a seven-year absence. The city would remain the capital for the next ten years, before the government moved to Washington. At the time, there was no Library of Congress, so the Library Company of Philadelphia served as the de facto national library for members of Congress during these formative years in the country’s history.

Also during this time, the library continued to expand its collections. In 1792 it absorbed the nearby Loganian Library, with its nearly 4,000 volumes. Although just completed, the new building here on Fifth Street was already too small, requiring a new wing to the rear that opened in 1794. This growth would continue into the 19th century, through a variety of bequests and purchases from private collections. By 1851, the library had around 60,000 volumes, making it the second-largest in the United States, behind only Harvard’s library.

As a result, the library was again in need of more space. A solution to this problem came in 1869, when Dr. James Rush left the library nearly $1 million in his will, for the purpose of constructing a new building. However, it came with stipulations, most significantly that it had to be located at the corner of Broad and Christian Streets in South Philadelphia. This was far removed from the city center, and from the homes of most of the library’s patrons, so the gift caused considerable controversy. By a very narrow margin, library members ultimately voted to accept it, and the building—known as the Ridgway Library—was completed there in 1878. Because of its remoteness, though, the building was used primarily for storage and for housing rare books.

Around the same time that the Ridgway Library was completed, the Library Company began constructing a new downtown building. With a more convenient, central location, this would serve primarily as a lending library, and its collection focused on modern works. It opened in 1880 at the corner of Juniper and Locust Streets, replacing this Fifth Street building as the Library Company’s downtown facility. The old building was then sold, and it was demolished in the late 1880s to make way for an addition to the adjacent Drexel Building.

The Drexel Building was demolished in the 1950s as part of the development of the Independence National Historical Park. This project involved demolishing entire blocks in the area adjacent to Independence Hall, leaving only the most historically-significant buildings as part of the park. Most of this cleared land then became open space, but here on Fifth Street the Drexel Building was replaced by a replica of the old Library Hall. This building was completed in 1959 as the home of the American Philosophical Society.

Today, there is little evidence of the changes that have occurred here since the first photo was taken in 1859. Despite being barely 60 years old, the new building has the appearance of being from the 18th century, and it fits in well with the nearby historic buildings. There are hardly any differences between its exterior and that of its predecessor, and it even has a replica of the Franklin statue in the niche above the door. In the meantime, the original statue is probably the only surviving object from the first photo. The marble is now badly weathered, but it is on display inside the current home of the Library Company of Philadelphia, at 1314 Locust Street.