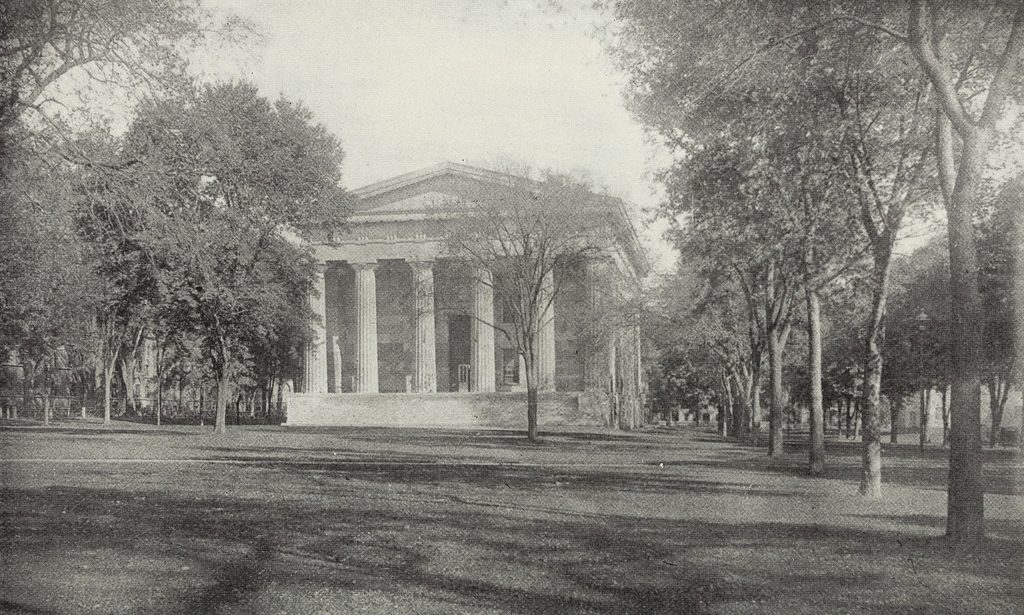

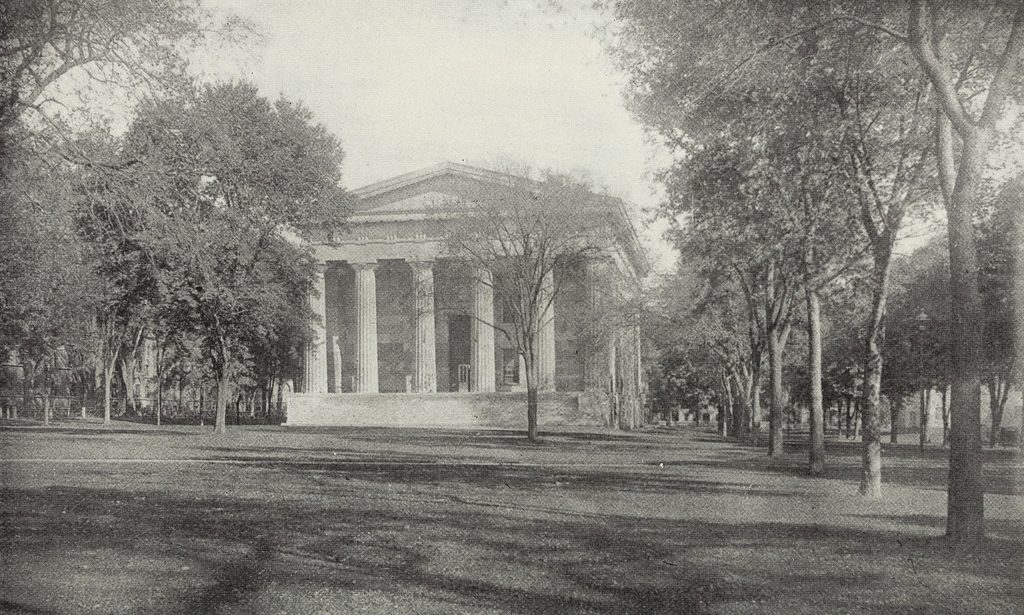

The Connecticut State House on the New Haven Green, seen from the south side of the building, sometime around the 1870s or 1880s. Image from The Connecticut Quarterly (1895).

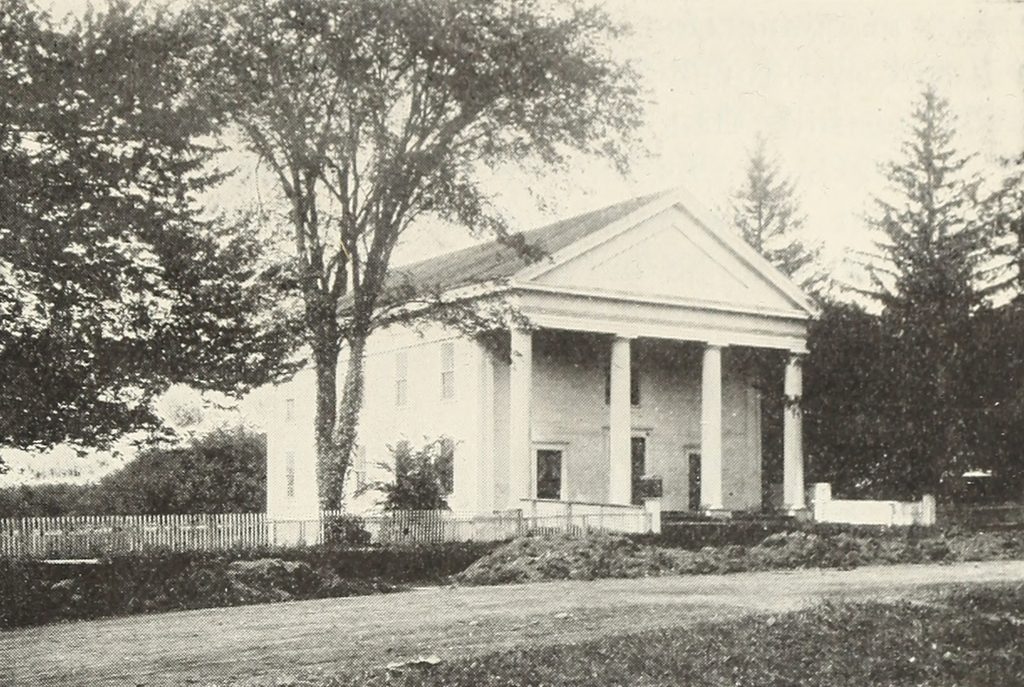

The scene in 2018:

During the early colonial period, the modern-day state of Connecticut actually contained two separate colonies. In the northern part of the state was Connecticut Colony, which was centered around Hartford on the Connecticut River. To the south, along the shores of Long Island Sound, was New Haven Colony, which was centered around its namesake town. These two colonies were ultimately merged in 1664, but the divide between Hartford and New Haven persisted for many years. In 1701, the two towns were designated as co-capitals of the Connecticut Colony, and legislative sessions altered between them, with the May session being held in Hartford each year, and the October session here in New Haven.

Two capital cities also meant two capitol buildings, and New Haven had a series of different state houses that were all located here on the New Haven Green. The last of these, which is seen in the first photo, was completed in 1831, replacing an earlier brick state house that had been in use since 1763. Its design was the work of Ithiel Town, a prominent Connecticut architect whose earlier New Haven works had included Trinity Church and Center Church, both of which are still standing nearby on the Green. Together, these three buildings demonstrated Town’s wide range of abilities, between the Federal-style Center Church, the Gothic-style Trinity Church, and the Greek Revival-style State House.

Town’s imposing design for the State House gave the building the exterior appearance of an Ancient Greek temple. It was built of stone, and had porticoes on both the north and south sides of the building, with classically-inspired columns, entablatures, and pediments. On the interior, the building included space for both the state and county governments. The basement and the first floor housed county offices, along with the county courtroom, a jury room, and various committee rooms. The upper floor had the two legislative chambers, with the House of Representatives at one end of the building and the Senate at the other, and there was also a room for the secretary and two rooms for the governor.

Following its completion in 1831, New Haven’s State House served, along with the older Hartford State House, as one of the state’s seats of government for more than 40 years. However, by the 1860s it was clear that maintaining two separate capitol buildings was both expensive and redundant. Railroads had significantly shortened the travel time between the two cities, which are a mere 35 miles apart, and the practice of having two capital cities apparently had more to do with each city’s sense of prestige than with any major convenience. Both cities lobbied hard to become the sole capital, and even Meriden threw its hat into the ring as a sort of compromise candidate. In the end, though, the question was settled by the voters of Connecticut, who chose Hartford as the capital, perhaps in part because of that city’s promise to contribute land and $500,000 toward the construction of a new State House.

The final legislative session at the New Haven State House was held here in 1874, and the following year Hartford took over as the state’s only capital. The new State House was completed in 1878, and still stands in Hartford’s Bushnell Park. In the meantime, the old 1797 State House was used as Hartford City Hall for many years, and it has since been preserved as a museum. However, here in New Haven the public sentiment was strongly divided over the fate of the city’s former State House. Having been vacated by both the state government and the county courts, the building was in need of a new use, and many argued in favor of preserving it and converting it into a public library. Perhaps with this proposal in mind, city voters approved an 1887 referendum to spend $30,000 on repairs to the building. However, the city council overruled this decision, and determined to demolish the iconic structure instead.

Even in the 1880s, long before the modern historic preservation movement gained widespread appeal, this was a highly controversial decision, with many praising the building’s architecture and its symbolic significance to the city of New Haven. Among the outside voices calling for its preservation was the Boston Advertiser, which published an editorial to that effect in 1889. In it, the newspaper argued:

That old State House is a priceless memento of a glorious past. It is a perpetual reminder that New Haven was originally an independent colony, and that, for nearly two centuries and a half it shared with Hartford the honor of being a state capital. Within those walls were uttered words whose echoes reached the continent and beyond the sea. Its style of architecture suggests the classic learning which, from the beginning, has been more faithfully taught in that locality than anywhere else in the world. . . . To tear down that building would be to obliterate one of the chief milestones on the path of time.

Not everyone in New Haven saw the State House in such a light, though. Apparently still embittered at losing the capital contest to Hartford some 15 years earlier, the New Haven Register responded to the Advertiser with an editorial of its own, arguing:

It will be news to most New Haveners to be told that the State House is a “priceless memento of the glorious past.” It is not, nor has it ever been priceless. It is a memento of New Haven’s folly in allowing Hartford to gobble up the capital. It is a perpetual reminder that New Haven in the past has shown a deplorable lack of public spirit in important crises. It is not a “chief milestone on the path of time.” Rather it is an encumbrance, a public nuisance, a bone of contention, an eyesore, a laughing stock, a hideous pile of brick and mortar, a blot on the fair surface of the Green. The Boston paper doesn’t know what it is talking about.

Both of these excerpts are quoted from The New Haven State House, a book that was published in 1889 shortly after the building was demolished. Interspersed within this history of the building were a number of advertisements, several of which attempted to use the demolition as a marketing strategy. One such ad declared “Two Great Mistakes! The greatest mistake ever made by New Haven people is shown by the destruction of the State House. The Second Mistake is in supposing that B. Booth has only second hand and auction goods at 388, 390 and 392 State St.” Another simply stated “The State House Gone. The City Market Remains,” and a third was for a photographic studio that promised “the Best Views of the Old State House that were made.”

Following the demolition of the State House, the area was cleared and reverted to open park land, as part of the New Haven Green. However, this western portion of the Green, known as the Upper Green, was also the city’s colonial-era burial ground, where an estimated 4,000 to 5,000 people were buried. The headstones have long since been removed – aside from a small portion of the graveyard that is located in the basement of Center Church – but the remains themselves are still interred here under the Green. Today, though, there is little here to suggest the presence of a burial ground, or the former presence of a state capitol building. However, the New Haven Green is not without historic buildings, as three early 19th century churches still stand on the far right side of this scene, including the two designed by Ithiel Town.