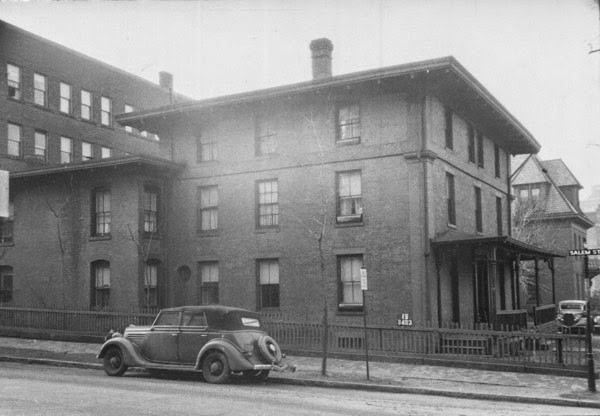

The house at 45 Pearl Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The scene in 2018:

The mid-19th century was a time of considerable growth for Springfield, which nearly tripled in population between 1820 and 1840. This led to the opening of a number of new streets in the downtown area, including Pearl Street, which originally extended one block from Chestnut Street west to Spring Street. This particular house, located at what would eventually become the corner of Mattoon Street, was the first to be built on the new street. It was completed in 1847, and was originally the home of Abel Howe, a mason who evidently designed and built the house himself. The exterior was built of brick, and it featured a square, Italianate-style design, with a flat roof and wide overhanging eaves above the third floor.

Howe lived here until at least the early 1850s, but by the end of the decade he had moved to a house nearby on Salem Street. By about 1868, this house on Pearl Street was owned by Dr. Nathan L. Buck, a physician who, during the 1870 census, was living here with his wife Elmira and their two children, Fred and Nellie. At the time, his real estate was valued at $15,000 ($300,000 today), and his personal estate at $11,000 ($220,000 today). This wealth would have put him well within Springfield’s middle class, although these figures were lower than those of most of his neighbors.

The Buck family was living here as late as 1877, and Dr. Buck also had his medical practice here in the house. He was still listed as the owner of the property in the 1882 city atlas, but he evidently rented it, because he does not appear in the 1880 census or in any subsequent city directories. Instead, another physician, Dr. John Blackmer, was living here from about 1878 to 1883. Like Dr. Buck, he had his offices in the house, and during the 1880 census he was living here with his wife Ellen, daughter Nellie, son John, and a servant.

By 1885, the house was owned by Mary Shaw, a widow who was about 60 years old at the time. A native of Coventry, England, she and her husband Joseph immigrated to the United States in 1860, and by 1866 they were living in Springfield, where Joseph established himself as a brewer. He died in 1875, but Mary outlived him by more than 30 years. The 1900 census shows her living alone at this house on Pearl Street, but she evidently moved out soon after, because the subsequent city directories list her at a variety of different addresses until her death in 1906, at the age of 83.

The house was still owned by the Shaw family by 1910, but by this point it had been converted into a boarding house. Although there was just one resident in this large house during the 1900 census, the 1910 census showed 24 boarders living here. Nearly all were unmarried men in their 30s and 40s, and most held working-class jobs such as a carpenter, plumber, painter, tile layer, bookkeeper, and several chauffeurs, salesmen, and machinists. Six of them were immigrants, and most of the other boarders had previously lived in a different state before moving to Springfield.

By the 1920 census, the house was still in use as a boarding house. It was run by James and Mary Alexander, and they rented rooms to 24 boarders. James was an immigrant from Greece, and Mary from England, and many of their tenants were also immigrants, including people from Canada, Ireland, Greece, Russia, Holland, and Switzerland. The Alexanders would continue to keep a boarding house here until as late as 1939, around the time that the first photo was taken, but they are not listed on the following year’s census. Instead, the 1940 census shows Thomas and Katherine Van Heusen living here and running the boarding house. They paid $85 per month in rent, and in turn they rented rooms to 19 boarders.

Up until this point, the exterior of the house had retained much of its original appearance, despite having been used as a boarding house throughout the first half of the 20th century. However, in 1948 it underwent a major renovation to convert it into a commercial property. The porch was replaced by a new storefront, the overhanging waves were removed, a third story was added to the rear section, and many of the first floor windows were bricked up, among other alterations. The building is still standing today, but because of these changes its exterior bears little resemblance to its original appearance. Despite this, though, it survives as one of the oldest buildings in the area, and it is a remnant of the many upscale homes that once lined this block of Pearl Street.