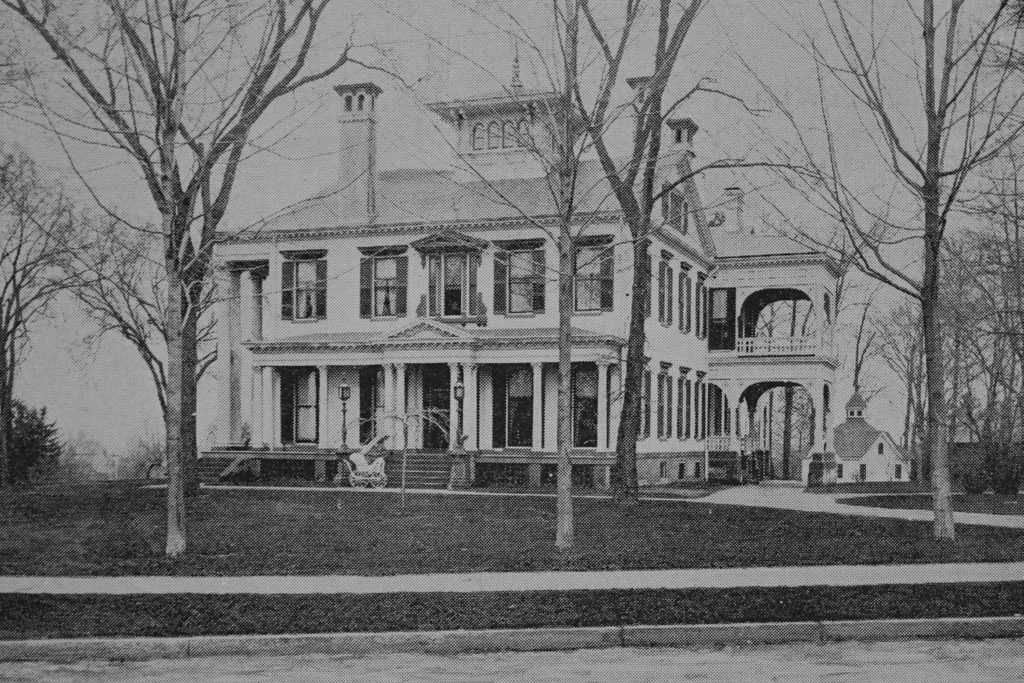

The house at 104 Maple Street in Springfield, around 1938-1939. Image courtesy of the Springfield Preservation Trust.

The scene in 2017:

The house in the first photo was built in 1850 for Solyman Merrick, a tool manufacturer who had previously lived nearby in a house that still stands at the corner of Maple and Union Streets. Best known as the inventor of the monkey wrench, Merrick had patented his design in 1835 and later sold it to Bemis & Call, a Springfield-based tool manufacturer. He married his first wife, Henrietta Bliss, in 1841, and that same year they moved into the house at the corner of Maple and Union Streets. However, they were only there for a few years, because Henrietta died in 1845 and Solyman sold the property two years later. Then, in 1848, Merrick remarried to Anne Clapp, and in 1850 they moved into this new house at 104 Maple Street.

Although his new home was built less than a decade after his first one, it represented a dramatic shift in architectural styles. His first home had been a fairly conservative Greek Revival-style home, but his new one was a far more ornate Italian villa, designed by architect Leopold Eidlitz. It was one of the first buildings in Springfield to be designed by a formally-trained architect, and caused a considerable stir in the small but growing community. Born in Prague in 1823, he later came to America and studied under renowned architect Richard Upjohn, before starting his own firm in 1846. One of his first works was the home of P. T. Barnum in Bridgeport, and soon afterward he designed this house for Merrick in Springfield. He would go on to have a successful career, including designing Springfield’s old city’s hall, and later in life he was one of several architects who worked on the New York State Capitol.

Unfortunately for Solyman Merrick, he died in 1852, just two years after the completion of this house. He was only 45 at the time, and he left behind his wife Anne and their three-year-old son, William. The two of them continued to live here after Solyman’s death, along with Anne’s sister Caroline and her husband, Albert D. Briggs. During the 1860 census, Albert and Caroline lived here with their two young sons, John and Edward, and the household also included lawyer Franklin Chamberlin and his wife Mary, along with four live-in servants.

Albert Briggs was a bridge builder who, as a boy, had moved with his family to Springfield from Brattleboro, Vermont. When he got older, he found work as as a surveyor and engineer during the construction of the Western Railroad between Springfield and Albany. Despite being barely 20 years old, he was also an assistant engineer for the railroad bridge across the Connecticut River, where he worked under William Howe, the inventor of the Howe truss design. This set Briggs on a successful career as a bridge builder, and he worked closely with Howe for the next decade and even purchased Howe’s patent rights for several states. By the time he moved into this house in the 1850s, he had established a successful business that was building bridges in all parts of the country.

Aside from his bridge building, Briggs was also involved in politics, serving as a city alderman in 1864 and as mayor from 1865 to 1867. He did not, however, serve in the Civil War, but his widowed sister-in-law did. Anne Merrick was 42 years old at the start of the war, and she joined the war effort as a nurse for the 10th Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry. The history of this regiment, published in 1909, highlights her service, writing that:

“When, in the fall of 1861, typhoid fever was decimating the ranks of the Tenth and Brighwood, two ministering angels in human form, left their happy northern homes to serve these men in camp. Their stay with the regiment was a blessing from the start and every soldier, whether well or ill, has never failed to sing their praises when the names of Mrs. Merrick and Miss Wolcott were mentioned.”

The author, Alfred S. Roe, went on to write:

“Mrs. Merrick, it will be observed, was a widow when she volunteered to minister to the suffering soldiers in Washington. In this capacity she continued until, herself stricken with fever, she was compelled to return home, Miss Wolcott accompanying her.”

Anne Merrick had died long before the book was published, but her fellow nurse, Helen Wolcott, wrote a short letter to the author, describing their experience in the war:

“In regard to Mrs. Merrick and myself, nurses in the old Tenth Regiment, I could tell you more than I can write. It is all very fresh in my mind. The first night we slept on the floor of the tent. The next day the carpenter made us a very good bedstead. I shall never forget how glad the sick men were to see us, as one said, ‘Any one in petticoats.’ I fully recall one from Northampton, who died very soon, his parents coming at the very last moment.”

After her service in the war, Anne Merrick continued to live here with her son William, along with Alfred and Caroline Briggs, until her death in 1879. In the meantime, William followed in his father’s footsteps as a businessman, eventually becoming treasurer of the Springfield Gas Light Company as well as a director of the John Hancock Bank. He was also involved in several city organizations, including the library and the Springfield Hospital, and he donated the land for Merrick Park, at the corner of State and Chestnut Streets. However, like his father, William died young, in 1887 at the age of 37.

Albert Briggs died two years after Anne Merrick, in 1881, but Caroline continued to live here in this house, even after William’s death. She died in 1895, and the house was subsequently sold to lumber dealer Frank C. Rice. He was the president of the Rice & Lockwood Lumber Company, and during the 1900 census he was living here with his wife Emily and their son Julian, along with Emily’s mother Charlotte Anderson and sister Martha Anderson.

A decade later, during the 1910 census, Frank and Julian were still living here, but Emily had died in 1907 from appendicitis, at the age of 50. Frank lived here until around 1916, when he moved into an apartment nearby at 169 Maple Street, and he sold this house to Dr. Richard S. Benner, an obstetrician who lived here with his wife Marion and their four children.

Dr. Benner lived here until his death in 1939, right around the same time that the first photo was taken. Marion continued to live here for at least a few more years, although by the mid-1940s she had moved to Randolph Street in Forest Park. In the meantime, her old house stood here on Maple Street until around the early 1960s. Despite its historical significance as the home of the inventor of the monkey wrench, and despite its importance as one of the city’s early architectural landmarks, it was demolished and replaced with the office building that now stands on the site.