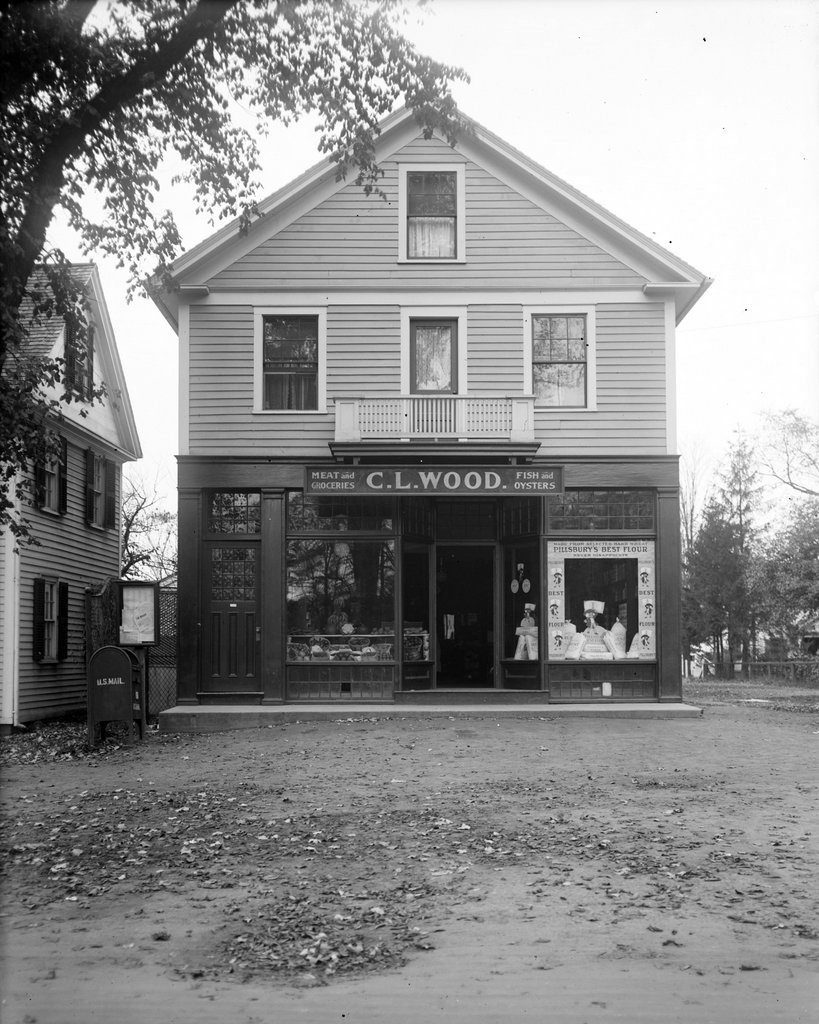

The Mark Twain House on Farmington Avenue in Hartford, around 1880. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The house in 2018:

Samuel Clemens, better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was born and raised in Missouri, and he is probably best identified with the Mississippi River, where many of his works are set. However, Mark Twain actually spent much of his literary career in Hartford. He moved here in 1871, a year after his marriage to Olivia Langdon, and the couple initially rented a house here in the Nook Farm neighborhood. Mark Twain came to Hartford in part because it was the home of his publisher, Elisha Bliss. However, the city also enjoyed a thriving literary community, with prominent authors such as Charles Dudley Warner and Harriet Beecher Stowe also living in Nook Farm.

After several years of renting, Mark Twain decided to build a house of his own. He purchased a lot on Farmington Avenue, just around the corner from Harriet Beecher Stowe’s house on Forest Street, and he hired architect Edward Tuckerman Potter, who designed this ornate High Victorian Gothic-style house. It was completed in 1874, and the family would go on to live here for the next 17 years. At the time, the couple had two young daughters, Susy and Clara, and a third daughter, Jean, would be born in 1880. They had one other child, a son named Langdon, but he died in 1872 at the age of 19 months. The first photo was taken around the time that Jean was born, and it shows the house as it appeared before the servants’ wing was added to the right side of the scene in 1881.

Mark Twain was already a prominent author by the time he moved into this house, having recently published books such as The Innocents Abroad (1869) and The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today (1873). However, his 17 years at this house would become perhaps the most productive of his career, and he wrote many of his most famous works here, including The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), A Tramp Abroad (1880), Life on the Mississippi (1883), The Prince and the Pauper (1881), Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1884), and A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889).

Despite significant literary success throughout the 1880s, Mark Twain suffered several major financial setbacks in the early 1890s. Because his Hartford house was so expensive to maintain, he and his family moved to Europe, where he went on lecture tours. He eventually succeeded in paying off his creditors and becoming financially stable again, but during this time he also experienced struggles within his own family. In 1896, his youngest daughter Jean was diagnosed with epilepsy – which would ultimately lead to her early death in 1909 at the age of 29 – and only five months later, in August 1896, his 24-year-old daughter Susy died of spinal meningitis. Her death hit the family particularly hard, and they never lived in this house again, in part because of its association with Susy.

Mark Twain finally sold this house in 1903, a year before his wife Olivia’s death. He would eventually return to Connecticut, although not to Hartford. In 1908, he built a home in Redding, near the southwest corner of the state in Fairfield County. He named it Stormfield, after his short story “Captain Stormfield’s Visit to Heaven,” which would prove to be his last story published during his lifetime. It was at Stormfield that, on Christmas Eve in 1909, Jean drowned after apparently having a seizure in the bathtub. Less than four months later, Mark Twain also died at his Redding house, having outlived his wife and three of his four children.

In the meantime, the new owner of his Hartford home was Richard M. Bissell, an insurance executive who would later go on to serve as president of The Hartford for many years. He and his wife Mary had three children who grew up here, including Richard M. Bissell, Jr., who was born in 1909. The younger Richard went on to become a high-ranking CIA executive during the Cold War. He was involved in the development of the U-2 spy plane, and he was later appointed Deputy Director for Plans in 1959, a position that put him in charge of planning clandestine operations. These included the disastrous 1961 Bay of Pigs Invasion, the failure of which ultimately led to his departure from the CIA in 1962.

Richard Bissell, Jr. spent the first eight years of his life here in this house, before he and his family moved to Farmington in 1917. The elder Bissell subsequently leased the house to the Kingswood School, a private school for boys that Richard Bissell, Jr. attended. The Bissell family sold the property in 1920, but the sale included a stipulation that allowed Kingswood to remain here until 1922. They did so, and after they left the new owners announced plans to demolish the house and build an apartment building on the site. These plans were eventually scrapped after a significant public outcry, and the interior of the house was instead divided into 11 apartment units in 1923.

The threatened demolition of the historic house helped to spur support for its preservation, and in 1929 it was purchased by the Mark Twain Memorial and Library Commission. The ultimate goal of this organization was to restore the house to its original appearance, but these plans took many years to come to fruition. In the meantime, the first floor became a branch of the Hartford Public Library, and the upper floors continued to be rented to residential tenants while the organization raised funds for the restoration.

This work was finally completed in 1974, and today the entire house is open to the public as a museum. Thanks to the preservation efforts that began nearly a century ago, there is very little difference between these two photos, aside from the addition of the 1881 servants’ wing. The neighboring Harriet Beecher Stowe House has also become a museum, known as the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center, and both of these houses are now designated as National Historic Landmarks because of their literary significance.