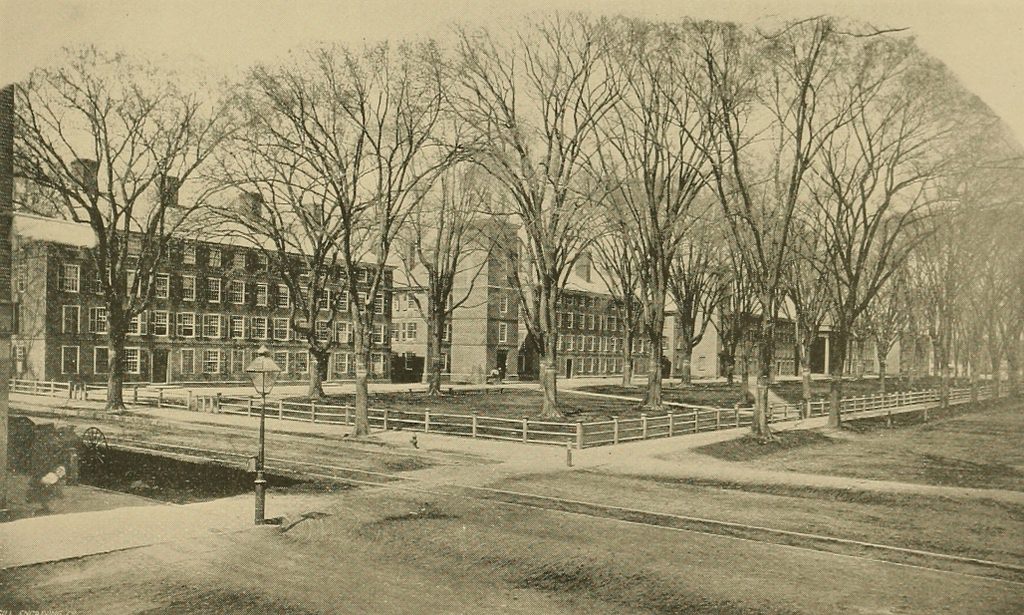

The Old Brick Row on the Yale campus, seen from the corner of College and Chapel Streets in New Haven, in 1863. Image from Yale University Views (1894).

The scene in 2018:

Today, much of the Yale campus consists of ornate Gothic-style buildings that were constructed during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, prior to this time the campus consisted of a group of brick Federal-style buildings that ran parallel to College Street from the corner of Chapel Street. Collectively known as the Old Brick Row, these were built between 1752 and 1824, and they formed the heart of Yale University until the late 19th century, when the old buildings were steadily replaced by more modern ones. Only one building, Connecticut Hall, still survives from the Old Brick Row, although it is now surrounded by newer buildings and is hidden from view in the present-day scene.

The site of the Old Brick Row, now known as the Old Campus, was also the site of the first Yale building in New Haven, which was named the College House. It was completed in 1718, two years after the school moved to New Haven, and was located in the foreground at the corner of College and Chapel Streets. During the early years, it was the only building on campus, but it was later joined by other buildings, including Connecticut Hall, a dormitory that was completed in 1752 and was, in later years, known as South Middle College. Then, in 1763, the First Chapel – later known as the Atheneum – was built to the south of Connecticut Hall. College House was demolished in 1782, but the other two buildings were still standing when the first photo was taken in 1863, with the First Chapel second from the right, and Connecticut Hall just to the right of it.

Following the demolition of the College House, Yale decided upon a campus plan that would involve new buildings to the south of the First Chapel and to the north of Connecticut Hall. This is regarded as the first such campus plan at any college in the country, and it consisted of a single row of buildings that alternated between long dormitories and smaller buildings that were topped with steeples. As part of this plan, Union Hall – later called South College – was built near where the College House had stood, on the far left side of the first photo. This was followed at the turn of the 19th century by the Lyceum, which stood immediately to the right of Connecticut Hall, and Berkeley Hall – later North Middle College – further to the right of it. The last two additions to the Old Brick Row came in the early 1820s, with the construction of North College on the extreme northern end of the row around 1821, and the Second Chapel, which was built between North Middle and North in 1824.

By the time the first photo was taken in 1863, the campus had also come to include buildings such as a library, laboratory, art gallery, and Alumni Hall, which was used as a lecture hall. The Old Brick Row continued to play a central role on the Yale campus throughout this time, but this would soon begin to change. In 1870, the school adopted a new campus plan, which called for the gradual replacement of the old buildings and the creation of a quadrangle that was surrounded by new Gothic-style buildings. This began at the northwestern corner of the block with the construction of Farnam Hall, Durfee Hall, and the Battell Chapel in the 1870s, although this did not immediately affect the Old Brick Row, which stood here for several more decades.

The first to go were South College and the Atheneum, both of which were demolished in 1893 to make way for Vanderbilt Hall, which was completed a year later. By this time, the rest of the Old Brick Row had found itself essentially surrounded by new buildings, hidden from view from the street and in the midst of a newly-formed quadrangle. These old, plain brick buildings looked increasingly out of place in the midst of the new, ornate Gothic-style brownstone buildings, and most were removed over the next few years. Both North Middle College and the Second Chapel were demolished around 1896, followed by the Lyceum and North College in 1901. South Middle College was also slated for demolition as part of the new campus plan, but it was ultimately saved, and was restored to its original Georgian-style design in 1905.

The present-day photo shows a few of the late 19th and early 20th century buildings of the Old Campus, most of which are now older than much of the Old Brick Row had been when it was demolished. In the distance on the extreme left is Vanderbilt Hall, with Bingham Hall (1928) at the corner, Welch Hall (1891) to the right of it, and Phelps Hall (1896) barely visible beyond the trees on the far right. South Middle College, which is once again known by its historic name of Connecticut Hall, is still standing in the quadrangle behind Bingham Hall, no longer visible from this angle. It is the only surviving remnant from the Old Brick Row, but in 1925 it was joined by McClellan Hall, which stands next to it on the quadrangle with a Colonial Revival design that matches Connecticut Hall and pays tribute to the long-demolished buildings of the Old Brick Row.