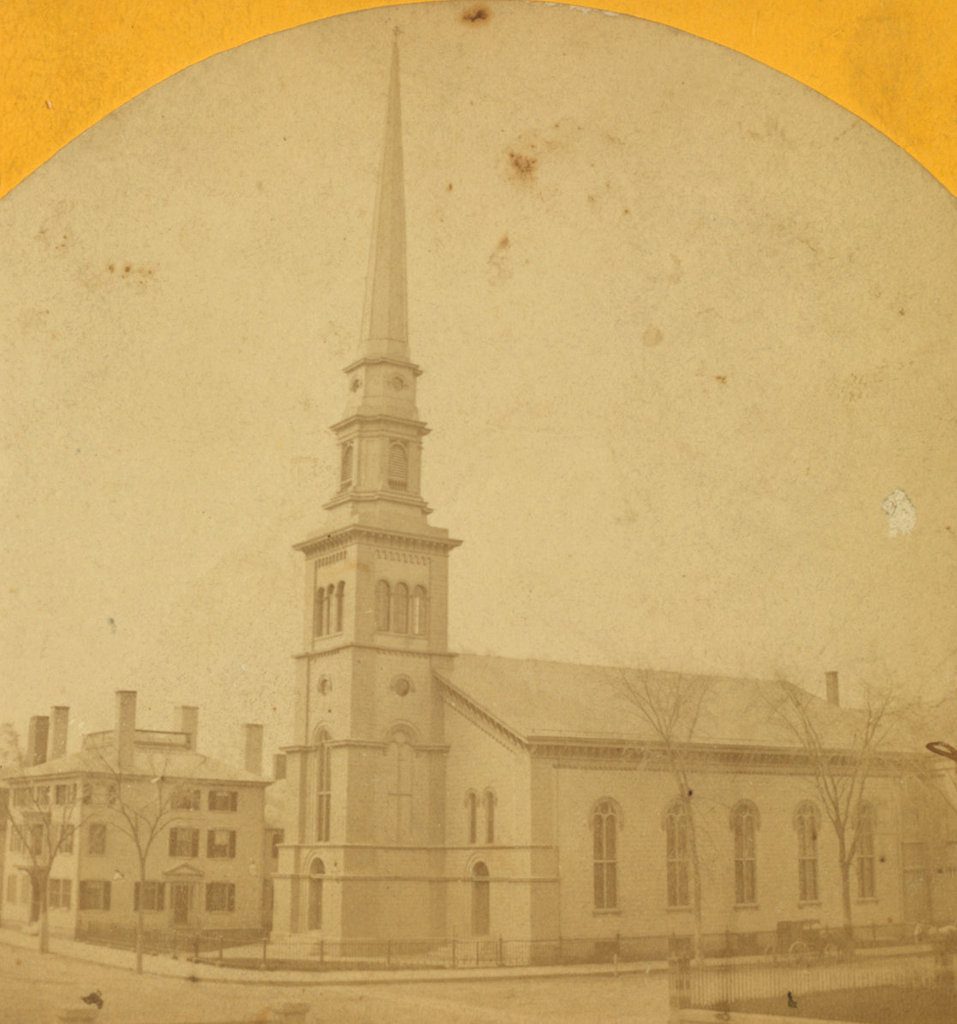

The First Baptist Church, at 54 Federal Street in Salem, around 1865-1885. Image courtesy of the New York Public Library.

The site of the church in 2017:

The first Baptist minister in Salem was none other than Roger Williams, who briefly served as pastor of the First Church in the 1630s, immediately prior to his famous banishment in modern-day Rhode Island. However, it would be some 170 years before a Baptist church was formally established here in Salem, when 24 parishioners formed the First Baptist Church in 1804. The following year the church installed its first pastor, 25-year-old Brown graduate Lucius Bolles, and around the same time construction began on a permanent church building here on Federal Street, just east of North Street.

The diary of William Bentley, the prominent Unitarian minister of the East Church in Salem, provides an interesting perspective on the early history of this church. At the time, Baptists were a religious minority in Massachusetts, where nearly all churches were Congregational Bentley’s diary reveals hostility toward the Baptists. For example, on January 9, 1805, the day when Reverend Bolles was ordained, Bentley wrote:

A very rainy day & the day designated for the public ordination of a Baptist Minister in Salem. It was a dark day, because we were afraid of the uncharitableness of this Sect which has been the most illiterate in New England. All the ministers were invited. The Tabernacle was opened for the services. I did not attend. No Congregational minister of the Town was present. Dr. Stillman of Boston preached.

A month later, there was a tone of sarcasm when he wrote that “It is said that Mr. L. Bolles does not incline to dip [baptize] in the very cold weather as it too much endangers the health of the Spectators. The public owes him many thanks.” Then, on April 14, following the baptism of 10 more new members, Bentley complained of the Baptists luring members away from the established Congregational churches, writing:

It is said that the Clergy of the Town are about to print a refutation of the Baptists as the Baptists consider as free plunder all the members of their churches & rebaptise all who have been sprinkled at any age or baptised in any form in infancy. This superstition has all its fury at present in this place. Its violence must burst. Still like a storm, it may be short & leave many a wreck on the shore especially when many are too nigh to escape. I cannot think our Clergy equal to the controversy.

The brick, Federal-style Baptist church was completed later in 1805, and was dedicated on January 1, 1806. On that day, Bentley wrote, “This day was appointed to dedicate the New Baptist Brick Meeting House in Salem & to ordain Charles Lowell in the West Church in Boston. I preferred to employ the fine weather in a visit to Boston.” However, later in the same entry he gave some begrudging praise to Bolles:

In Salem, Mr. Bolles preached at the dedication & as usual in such occasions gave the concourse some history of his newly gathered Church. Its rapid progress in fifteen months since his first mission to Salem, is an honour to his perseverance & an example to his Superiors.

Notwithstanding Reverend Bentley’s scorn, the Baptists grew at a rapid pace upon completion of this church building. The congregation more than doubled in size in 1806, and by 1813 it had over 300 members. The church evidently welcomed all races, with Bentley noting in one 1810 entry that “8 young females & one Negro man” were baptized here. Earlier in 1810, he had also commented on how Thomas Paul, the pastor of the First African Baptist Church in Boston, had previously preached here at the church. He was apparently well-received at the church, but was ridiculed by some townspeople and was denied a seat inside the stagecoach:

[I]n the past actually the Negro Minister Paul preached repeatedly in the Close Baptist Meeting House accompanied & assisted by their Pastor. In consequence one family only discovered displeasure, but the wags of the town put a paper of dogrel rhymes in print & distributed them through the town. The Stage refused the Negro Minister a passage in the Stage within, but offered him a seat with the driver, which he angrily refused.

Over the next few years, the church did experience some fluctuations in its size, as many of the members left to form Baptist congregations in the neighboring towns. However, the church remained strong, and during its first 20 years it added 512 members. Reverend Bolles remained in the pulpit until 1826, when he resigned because of poor health and his new responsibilities as corresponding secretary of the Foreign Mission Board in Boston.

The first major changes to the church building came a year later in 1827, when it was expanded and a tower was added above the front entrance, as seen in the first photo. Further changes occurred around 1850, when the original Federal-style design was given Italianate details, such as the quoins on the corners and the arches above the windows. It was remodeled again in the late 1868, was damaged by a fire on October 31, 1877, and then repaired the following year. Although undated, the first photo was probably taken before the fire, and perhaps even before the 1868 renovations.

Much of the tower is cut off in the first photo, but by the turn of the 20th century it consisted of three stages, topped by an almost absurdly oversized illuminated clock. However, the tower was ultimately removed in 1926 due to the cost of maintenance, dramatically altering the exterior appearance of the building. It continued to be the home of the First Baptist Church throughout the 20th century, though, and despite the many changes it still retained significant historic value as the oldest surviving church building in the city.

Today, the historic church building is still standing, although no longer in its original location. The site was needed in order to build the new Essex County courthouse, so the congregation sold the property and relocated to a different church building on Lafayette Street in 2007. The following year, in December 2008, the 1,100-ton brick church was moved a couple hundred feet to the west, to the corner of Federal and North Streets. The exterior was restored and repointed, and the interior was converted into a law library for the new courthouse, which opened in 2012 as the J. Michael Ruane Judicial Center. The photo below shows the church at its current location, a little to the left of where it had once stood.