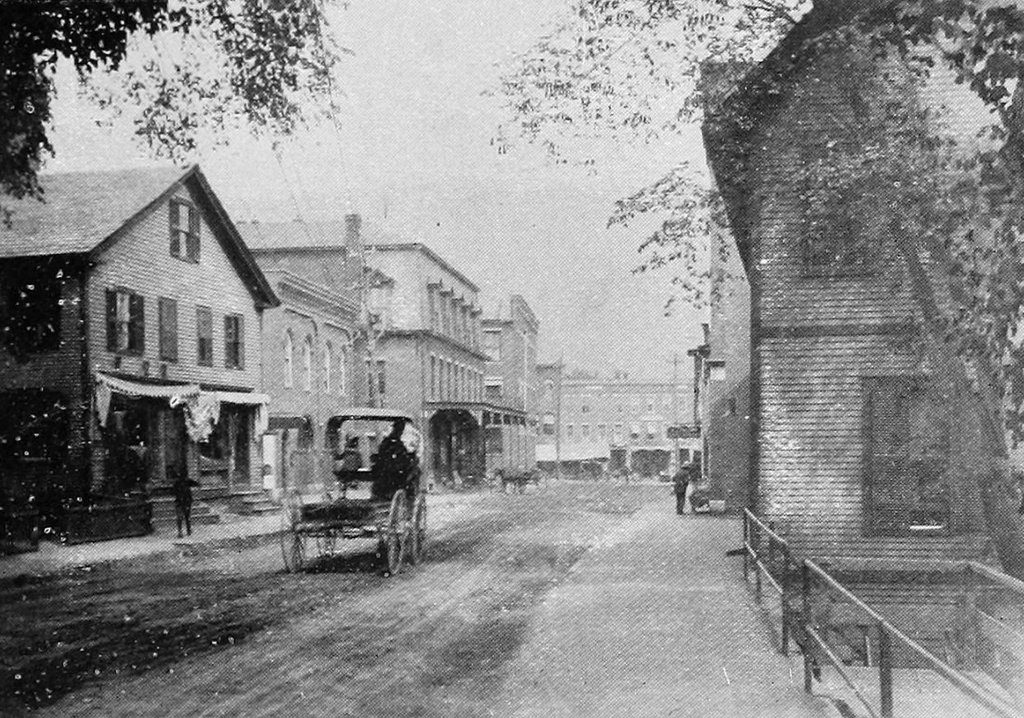

Looking south on High Street from the corner of Hampden Street in Holyoke, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

The scene in 2017:

Much of High Street in Holyoke has been remarkably well-preserved over the years, particularly this block on the west side of the street, between Hampden and Dwight Streets. It consists primarily of brick, three and four-story commercial blocks that were built in the second half of the 19th century, during the early years of Holyoke’s development as a major industrial center. The scene had largely taken on its present-day appearance by the time the first photo was taken in the early 1890s, and today the only significant difference is a noticeable lack of horse-drawn carriages.

According to district’s National Register of Historic Places listing, the one-story building in the foreground was built in the mid-20th century, but it seems possible that it might actually be the same one from the first photo, just with some major alterations. Either way, this is the only noticeable change in the buildings on this block. Just beyond this building are two matching three-story buildings, located at 169-175 High Street. These are perhaps the oldest buildings in the scene, dating back to around 1855, and have a fairly plain exterior design, unlike the more ornate building further down the street.

To the left of these two buildings is the four-story Dougherty’s Block, at 177-179 High Street. This was built sometime around the late 1880s, and was probably the newest building in the first photo. Beyond it is the 1870 Taber Building, with its distinctive ornate pediment above the third floor. However, the most architecturally-significant building in this scene is the Second Empire-style Caledonia Building at 185-193 High Street. It was built in 1874, and was originally owned by Roswell P. Crafts, a businessman who went on to become mayor of Holyoke in 1877 and from 1882 to 1883. The building was later owned by the Caledonian Benefit Society, which provided aid for Scottish immigrants.

Beyond the Caledonia Building, most of the other buildings also date to between 1850 and 1880. These include, just to the left of the Caledonia Building, the Johnson Building at 195 High Street and the R.B. Johnson Block at 197-201 High Street, both of which date back to around the 1870s. Further in the distance is the 1850 Colby-Carter Block at 203-209 High Street, and the c.1870 Ball Building at 211-215 High Street. The only noticeable change in this section is the six-story Ball Block, at the corner of Dwight Street. It was completed in 1898, a few years after the first photo was taken, and is visible on the far left side of the 2017 photo.

More than 125 years after the first photo was taken, this section of High Street survives as a good example of Victorian-era commercial buildings, representing a range of architectural styles from the plain brick buildings of the 1850s, to the more ornate styles of the 1870s and 1880s. Holyoke is no longer the thriving industrial city from the first photo, having experienced many years of economic stagnation since the mid-20th century. However, this has probably contributed to the survival of so many 19th century buildings, since there has been little demand for new construction, and today these historic buildings and streetscapes are among the city’s greatest assets.