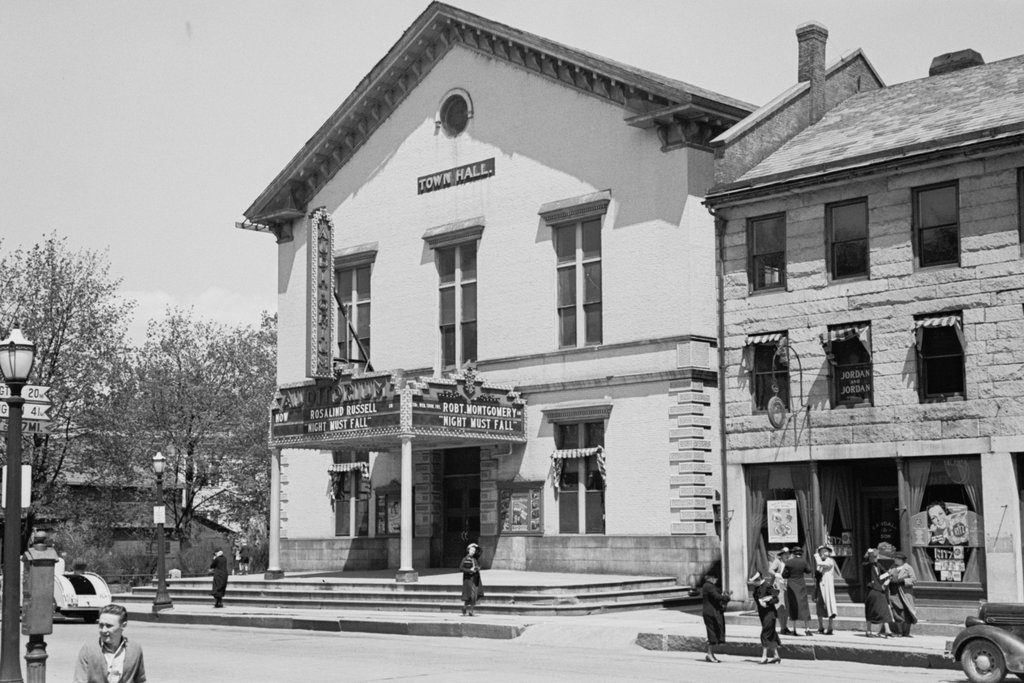

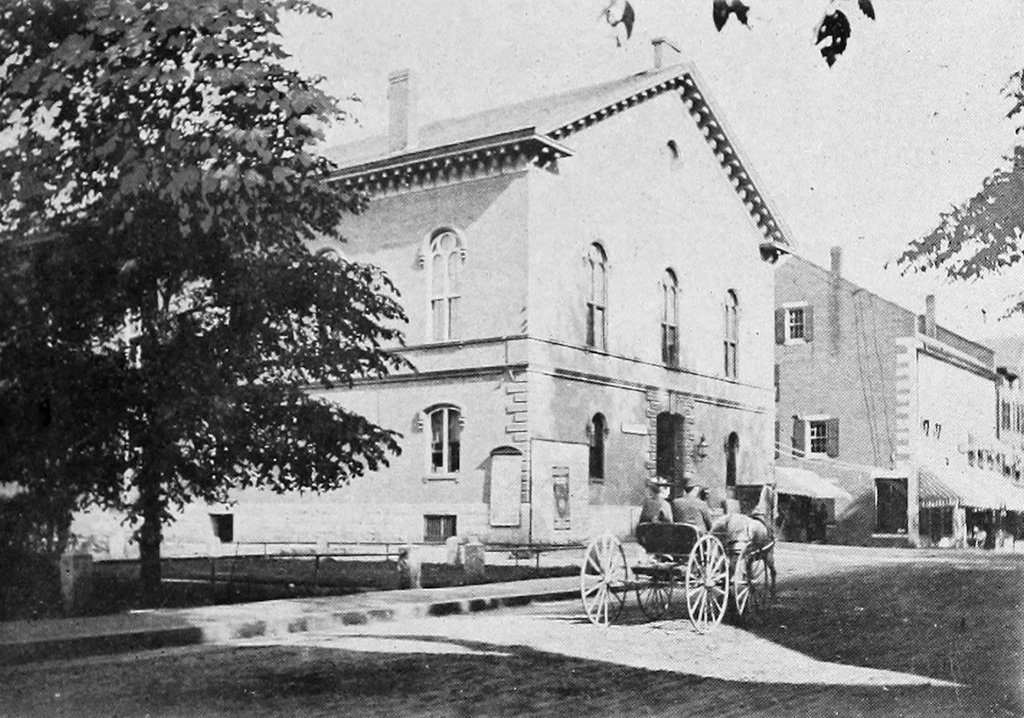

The Custom House at the corner of Orange and Derby Streets in Salem, around 1906. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2017:

In a city with countless historic buildings from the 18th and 19th centuries, one of the landmarks is the Salem Custom House, which was built in 1819 at the corner of Orange and Derby Streets. At the time, Salem was one of the busiest seaports in the country, with ships arriving with a wide range of cargoes from around the world, and the Custom House was located directly across the street from Derby Wharf, the largest of the many wharves in the harbor. It was also situated in the midst of many fine mansions, including the home of shipbuilder Benjamin Hawkes, which can be seen on the right side of both photos.

The imposing design of brick Custom House represented the presence of the United States government here in the port. Long before income tax and other direct taxes, the vast majority of the federal revenue came from duties on imported goods, so this building had an important role in the nation’s finances. For example, in 1819, the year that this building was completed, the customs duties across the country amounted to over $20 million, which comprised more than 80 percent of the total federal revenue of $24.6 million. By 1832, this had risen to nearly 90 percent, and included some $543,000 in revenue that was collected here in Salem. Although only a tenth of the revenue that was collected in Boston during that year, it was enough to rank Salem sixth among all customs districts in the country.

Today, despite its architectural value and its importance to Salem’s maritime history, the Custom House is probably best known for its association with Nathaniel Hawthorne, who immortalized the building in the introduction to his 1850 novel The Scarlet Letter. A native of Salem, Hawthorne returned to his hometown in 1846 when he was appointed Surveyor of the Port of Salem, with an office here in the Custom House and a salary of $1,200 per year. By this point, the 41-year-old Hawthorne had achieved only moderate success as a writer, and this job provided some much-needed financial stability for him and his growing family.

Hawthorne had managed to obtain the position thanks to his close friendships with leading members of the Democratic Party, including future president Franklin Pierce. However, the job – which involved weighing and measuring incoming cargoes – interfered with his literary career, and he did very little writing during his time as surveyor. The position proved short-lived, though, thanks to the Democratic loss in the 1848 presidential election. The victorious Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor, took office on March 4, 1849, and just three months later Hawthorne was dismissed from the Custom House.

Embittered by this dismissal, and with plenty of spare time on his hands, Hawthorne poured his emotions into his writing. From the late summer of 1849, until February 1850, he wrote The Scarlet Letter in the third-floor study of his home on Mall Street. This novel proved to be his literary breakthrough, and helped to establish him as one of the leading American authors of the era. The dark themes and bleak ending of the novel likely reflected his mood during this period of his life, but he was also more explicit in showing his anger. The novel begins with a lengthy introduction, titled “The Custom-House.” It takes up nearly 20 percent of the entire novel, and yet has very little to do with the actual plot of the story, aside from explaining how the present-day narrator discovered the 17th century story of Hester Prynne and the scarlet letter here in the Custom House.

However, this explanation comes as almost an afterthought at the end of the introduction, which is otherwise a long, semi-autobiographical polemic against both the Custom House and the city of Salem as a whole. By the time Hawthorne had taken his position here at the Custom House, Salem had seen a significant decline in its shipping industry. It had peaked in prosperity during the first few decades of the 19th century, around the time that this building was opened, but by mid-century the waterfront area featured rotting wharves and a Custom House building that was far too large for the modest amount of commerce in the city. In his introduction, Hawthorne described the area surrounding the Custom House, writing:

In my native town of Salem, at the head of what, half a century ago, in the days of old King Derby, was a bustling wharf—but which is now burdened with decayed wooden warehouses, and exhibits few or no symptoms of commercial life; except, perhaps, a bark or brig, half-way down its melancholy length, discharging hides; or, nearer at hand, a Nova Scotia schooner, pitching out her cargo of firewood—at the head, I say, of this dilapidated wharf, which the tide often overflows, and along which, at the base and in the rear of the row of buildings, the track of many languid years is seen in a border of unthrifty grass—here, with a view from its front windows adown this not very enlivening prospect, and thence across the harbour, stands a spacious edifice of brick.

He went on to describe the exterior appearance of the building, giving particular attention to the carved eagle above the main entrance:

Its front is ornamented with a portico of half-a-dozen wooden pillars, supporting a balcony, beneath which a flight of wide granite steps descends towards the street. Over the entrance hovers an enormous specimen of the American eagle, with outspread wings, a shield before her breast, and, if I recollect aright, a bunch of intermingled thunderbolts and barbed arrows in each claw. With the customary infirmity of temper that characterizes this unhappy fowl, she appears by the fierceness of her beak and eye, and the general truculency of her attitude, to threaten mischief to the inoffensive community; and especially to warn all citizens careful of their safety against intruding on the premises which she overshadows with her wings.

Later in the introduction, he described the interior, noting that “The edifice—originally projected on a scale adapted to the old commercial enterprise of the port, and with an idea of subsequent prosperity destined never to be realized—contains far more space than its occupants know what to do with.” It is in one such space – a large, unfinished room on the second floor – that the narrator of The Scarlet Letter discovers the story of Hester, along with the old scarlet letter that she once wore. These had once belonged to the fictional Surveyor Pue, who had preceded the narrator in his position at the Custom House, and were said to have provided the inspiration for the novel.

Neither Surveyor Pue, nor Hester or her scarlet letter, actually existed, but otherwise the introduction provides a fairly accurate – if rather jaded – view of Salem and the Custom House in the middle of the 19th century. The building did see some renovations only a few years later, from 1853 to 1854, and included finishing the rooms on the second floor that Hawthorne had described, along with adding a cupola to the roof. However, the decline of the city’s shipping industry continued over the next few decades, until overseas trade had effectively ceased by the 1870s.

When the first photo was taken around 1906, the building was still in use as a custom house. It had been painted yellow a few years earlier in 1901, but otherwise looked much the same as it had in Hawthorne’s day, aside from the cupola. Even the carved eagle, which had been installed in 1826, was still perched atop the building, and would remain there until it was removed in 2004 and replaced with a fiberglass replica. However, by this point the number appointed officials here in Salem had steadily dwindled. The position of naval officer was abolished here in 1865, followed by that of the surveyor a decade later. Finally, in 1913, Salem’s customs district was absorbed into Boston’s district.

Although no longer in a separate district, the old Custom House continued to be used by the Customs Service until 1936. It was then transferred to the National Park Service, becoming the centerpiece of the Salem Maritime National Historic Site. This park, which was formally established in 1938, was the first National Historic Site in the country, and today includes a number of historic structures along the Salem waterfront. The old Custom House has seen few changes during this time, and still looks essentially the same as it did when the first photo was taken, aside from the removal of the yellow exterior paint. The building is now open to the public, featuring a restored interior along with exhibits on the Customs Service, including the original eagle from the roof.