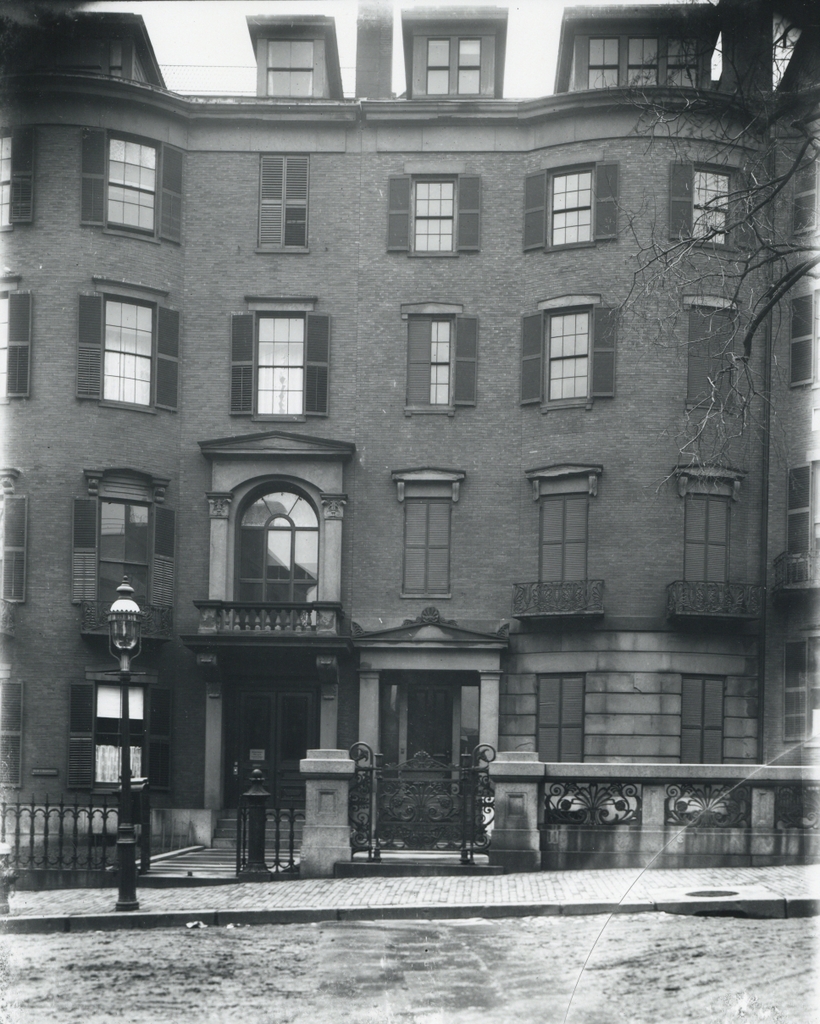

The birthplace of Edgar Allan Poe at 62 Carver Street (modern-day Charles Street South) in Boston, around 1931-1932. Image courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

The scene in 2021:

Boston was the literary center of the country during the mid-19th century, and many of the leading writers of this period were born in Boston or the vicinity. Perhaps the most famous of these was Edgar Allan Poe, although ironically he spent only short periods of his life in Boston, and he tended to have a dim view of his native city and the literary luminaries who lived here.

This may have been, at least in part, because of a very different family situation. While most of the other prominent Boston writers came from affluent, respectable families, Poe’s parents had been actors, a profession that, in early 19th century Boston, was seen as a lowly, possibly immoral profession. Orphaned as a young child, Poe would go on to lead a rather nomadic life, frequently moving between different cities on the east coast and eventually culminating with his mysterious death in Baltimore at the age of 40.

Poe was the second child of David and Eliza Poe, who lived in Boston from the fall of 1806 until the spring of 1809. Although they were both actors, Eliza was evidently the more talented of the two. She had begun her acting career at the age of nine, and by fifteen she was married to fellow actor Charles Hopkins. However, he died three years later in 1805, and Eliza remarried to David Poe in April 1806. Compared to Eliza, David was relatively new to acting. He had been studying to become a lawyer, but in 1803, at the age of 19, he abandoned it for the stage. Contemporary accounts indicate that he did seem to have some natural talent, but he also suffered from debilitating stage fright, which often caused him to speak his lines too rapidly, or forget them altogether.

The Poes moved to Boston a few months after their marriage, and their first appearance here was on October 13, 1806 at the Federal Street Theatre, in the comedy Speed the Plough by Thomas Morton. By this point Eliza was about six months pregnant, but she did not let this slow her down. She continued to perform in a variety of plays until about two weeks until the birth of her first child, William Henry Poe, on January 30, 1807. David continued to act during this time, including several supporting roles in Shakespearean plays, such as Laertes in Hamlet and Malcolm in Macbeth. However, Eliza’s maternity leave was short, and she was back on stage within less than a month.

During their time in Boston, the Poes performed alongside some of the most prominent actors of the era, including Thomas Abthorpe Cooper and James Fennell. During Cooper’s visit to Boston in early 1808, the Poes had a variety of supporting roles in his Shakespearean performances. Among other roles, David was cast as Malcolm in Macbeth, and Eliza played Ophelia in Hamlet, with Cooper as Hamlet. David and Eliza also performed together alongside Cooper, appearing as the Duke of Albany and Cordelia, respectively, in King Lear.

However, despite their successes on the stage, the Poes evidently struggled financially. They had to sustain an busy schedule of performances in order to make ends meet, and in the spring of 1808 they were the subject of several benefit performances. As noted by Arthur Hobson Quinn in Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography, these were special performances where the recipients would keep all of the profits, after the expenses from the performance were paid. The first benefit was held on March 21, with the Poes starring in The Virgin of the Sun. In advertising for the event, the Boston Commercial Gazette emphasized Eliza’s talents and work ethic, writing:

She has supported and maintained a course of characters, more numerous and arduous than can be paralleled on our boards, during any one season. Often she has been obliged to perform three characters on the same evening, and she has always been perfect in the text, and has well comprehended the intention of her author.

After reminding the readers of the many roles that she had preformed with such proficiency, the article concluded with:

We hope, therefore, that when the united recommendations of the talents of both Mr. & Mrs. Poe, are put up for public approbation, that the public will not only not discountenance virtuous industry and exertion to please, but will stretch forth the arm of encouragement to cheer, to support and to save.

However, with benefit performances such as this one, the intended recipients would earn the profits, but they would also be on the hook for making up the difference in the event that the proceeds did not cover the expenses. This was evidently the case for their March 21 performance, because a second benefit was subsequently scheduled for April 18. In advance of this, the Boston Democrat published an advertisement that noted:

[F]rom the great failure and severe losses sustained by their former attempts, they have been induced, by the persuasion of friends, to make a joint effort for public favor, in hopes of that sanction, influence, and liberal support, which has ever yet distinguished a Boston audience.

For this second benefit, they chose Friedrich von Schiller’s melodrama The Robbers, with David playing the role of Francis de Moor and Elizabeth playing Amelia. In organizing the benefit, they were assisted by their friends and fellow actors, Mr. and Mrs. Usher. The Poes and Ushers frequently performed together, and this would later lead to speculation about whether the Ushers were, many years later, the namesakes for one of Edgar Allan Poe’s most famous short stories.

It does not seem clear whether or not this second benefit was more successful than the first one. However, another source of speculation for later biographers was the fact that their second son, Edgar, was born exactly nine months and one day after this performance.

Because of incomplete records, it is hard to determine how many different houses the Poes lived in during their time in Boston. Their only confirmed place of residence was the house shown in the first photo, at what would become 62 Carver Street. They were definitely living here in the spring of 1808, when David Poe was listed here on tax records. And, although it is impossible to say for certain, the house is the most likely candidate for having been the birthplace of Edgar Allan Poe, who was born on January 19, 1809. Various sources have, at times, proposed 33 Hollis Street as his birthplace, but this conclusion was based on a faulty interpretation of city records.

The brick, Federal-style rowhouse at 62 Carver Street was built sometime after 1801 by Henry Haviland, a stucco worker who also ran a boarding house here. Haviland was living here in 1808, and his tenants included the Poes, John Hildreth, actor Daniel Grover, and ropemakers Joshua Barrett and Moses Andrew.

As was the case with her first pregnancy, Eliza Poe continued her busy acting schedule until shortly before Edgar was born. On January 13, just six days before he was born, she was playing the role of a peasant in The Brazen Mask, and she was back on stage just three weeks after his birth, appearing as Rosamonda in Abaellino, the Great Bandit on February 10.

Poe’s childhood in Boston proved to be very short-lived, with he and his family departing at the end of the season. David’s final role in Boston appears to have been Laertes in Hamlet on April 21, with Eliza playing the role of his sister Ophelia. Eliza would continue to appear in plays over the next few weeks, before concluding her time in Boston as Miss Marchmont in False Delicacy on May 12. The Poes subsequently departed Boston, and they were performing in New York by early September.

Unfortunately, life did not get any easier for the Poes after leaving Boston. David received negative reviews from some of the New York critics, and his final performance was on October 18, in Grieving’s a Folly. He was supposed to appear in the same play again two nights later, but a different play had top be substituted at the last minute, with contemporary accounts citing Poe’s “sudden indisposition” as the reason. This was often a euphemism for intoxication, leading some to suggest that Edgar Allan Poe may have inherited his alcoholism from his father. Either way, it marked the end of David’s acting career.

Eliza continued to act, and in December 1810 she gave birth to her third child, Rosalie, whose paternity is sometimes questioned. Eliza died a year later, likely from tuberculosis, at the age of 24, and David appears to have died around the same time. The three children were then split up, with young Edgar ending up with John and Frances Allan in Richmond, Virginia.

Edgar Allan Poe would eventually return to Boston several times over the course of his life. In 1827, while in the army, he was stationed at Fort Independence on Castle Island. It was during this time that Poe published his first work, Tamerlane and Other Poems. This 40-page pamphlet was printed in Boston by Calvin F. S. Thomas, although Poe’s name did not appear on it. Instead, the title page only indicated that it was “by a Bostonian.” However, only 50 copies were printed, and it received little attention. Today, only 12 copies are known to survive, making it one of the rarest books in the history of American literature.

Poe returned to Boston again in October 1845. By this point, he was a well-established author, and the Boston Lyceum invited him to speak at the Odeon Theatre. Although renamed, this was the same theater where, nearly 40 years earlier, Poe’s parents had regularly performed during their three seasons in Boston. Poe drew a sell-out crowd for the event, with the expectation that he would be presenting a new poem. Instead, however, he recited one of his early, obscure poems, “Al Aaraaf.” Written when he was a teenager, this was his longest poem, and it was particularly difficult to understand. Many in Boston saw this performance as an insult to the city, and Poe’s later remarks did little to mollify Bostonians.

Despite having been born in Boston, Poe had little regard for the city. This was particular true for its literary figures, whom he generally saw as overly moralistic in their writings, and he often referred to Bostonians as “Frogpondians,” after the frog pond on Boston Common. In responding to criticism of the Lyceum event, Poe published an essay in the Broadway Journal on November 1. In it, he acknowledged that he was born in Boston, writing:

We like Boston. We were born there—and perhaps it is just as well not to mention that we are heartily ashamed of the fact. The Bostonians are very well liked in their way. Their hotels are bad. Their pumpkin pies are delicious. Their poetry is not so good. Their Common is no common thing—and the duck-pond might answer—if its answer could be heard for the frogs.

Poe would make at least one more notable visit to Boston, in the fall of 1848. It was a little less than two years since the death of his wife Virginia, and he was in love with a married woman, Nancy “Annie” Richmond. Apparently out of desperation, he attempted suicided by overdosing on laudanum while he was in Boston. He was unsuccessful, but he ultimately died less than a year later in Baltimore, under mysterious circumstances.

In the meantime, Poe’s birthplace here in Boston would outlive him by more than a century, although given his disdain for Boston it seems unlikely that he would have been particularly concerned about its fate. And, Bostonians seemed similarly apathetic about it. While the homes of Poe’s Boston-area contemporaries like Emerson, Hawthorne, Alcott, and Longfellow have been preserved as museums, this was not to be the case for Poe’s birthplace.

By the early 20th century, this house was widely recognized as having been Poe’s birthplace, and a photograph and short article even appeared in the Boston Globe in 1924. At the time, the house was one in a long row of three-story brick buildings on the east side of Carver Street. The house on the right side of it, at 64 Carver Street, was still standing at that point, but it was demolished by the early 1930s, as shown by the parking area on the right side of the first photo in this post.

As for Poe’s birthplace at 62 Carver Street, its appearance likely had not changed much by the time the first photo was taken in the early 1930s. And, for that matter, its use had not changed much in the intervening years either. As was the case when Poe’s parents lived here in the early 1800s, it was likewise being used as a boardinghouse when the 1930 census was conducted several years before the photo was taken. According to the census, the boardinghouse was run by Margaret Trauvetter, a 53-year-old widow who lived here with her brother and seven boarders, all of whom were either single or widowed men. Most had working-class jobs, including a sailor, two clerks, a janitor, a storekeeper, and a stableman.

The house would remain here for several more decades, but in 1959 it was acquired by Boston Edison, which operated the adjacent Carver Street Substation. The house was demolished soon after, in order to expand the parking area for the substation. Today, the site is still a parking area, hidden behind a tall chain link fence with a privacy screen and barbed wire.

Although Poe’s birthplace at 62 Carver Street is gone, the two adjacent houses to the left are still standing, although because of street realignments this is now Charles Street South, rather than Carver Street. These two houses are the last survivors of the many three-story brick houses that once stood on this block, but they were built sometime in the late 1800s, so they would not have been here when Poe was born. However, there might still be one surviving remnant of Poe’s birthplace. The brick wall on the right side of the building in the present-day scene is a party wall that it once shared with its long-demolished neighbor. Because this was a shared wall, and because 62 Carver Street was much older, it is entirely possible that this was the original north wall of Poe’s birthplace, dating back to when it was built in 1801.

Overall, because his short childhood in Boston, and likely because of the mutual hostility between Poe and his native city, his origins here in Boston are often overlooked. However, he is not entirely forgotten here. While there are no markers here at this site to indicate that it was his birthplace, Poe is memorialized by a statue a few blocks to the north of here, at the corner of Boylston Street and Charles Street South. Unveiled in 2014, it features Poe, accompanied by a raven, walking with a partially-open briefcase, with papers spilling out of it. It is located only a short walk away from the frog pond on the Common that he was so fond of mocking, although—perhaps fittingly—the statue shows him walking away from the Common, with his back turned to Beacon Hill, where many of Boston’s elite had lived during his lifetime.