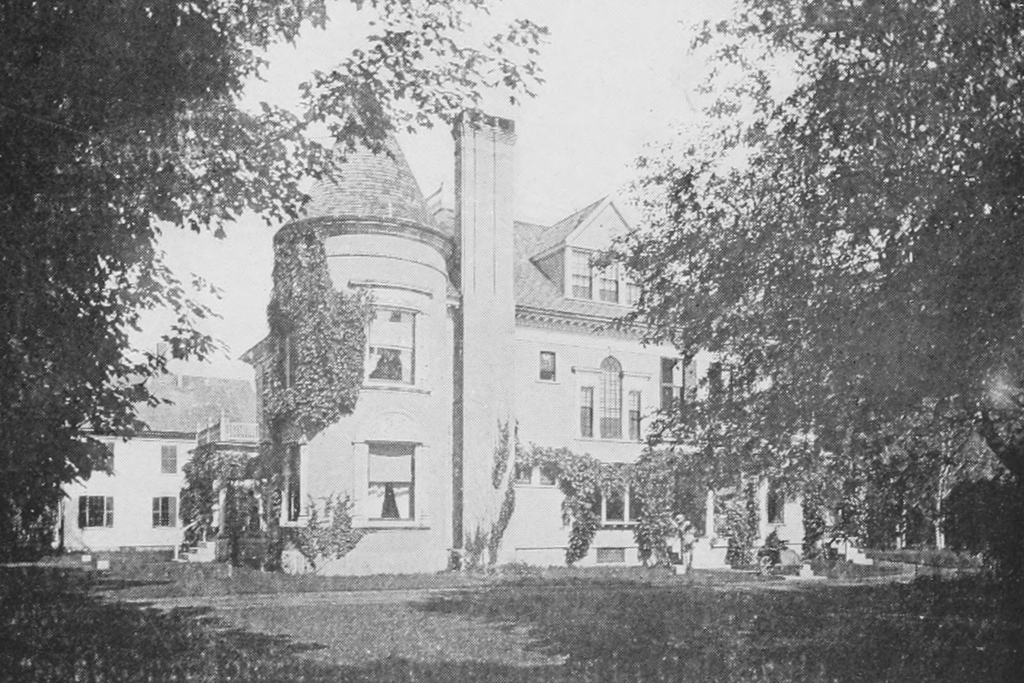

The Overlook house in Hartford, around 1900. Image from The Old and the New.

The scene in 2018:

This house, which was known as Overlook, was built at some point during the 19th century, probably around the 1870s based on its Second Empire-style architecture. For many years it was the home of Alfred E. Watson, a noted businessman and local politician. He was born in 1857 and he grew up in Hartford, where his father, Edwin C. Watson, manufactured agricultural tools in the firm of French, Watson & Co. Alfred attended nearby Dartmouth College, graduating in 1883, and that same year he married Mary Maude Carr of Montpelier.

Alfred Watson was primarily involved in the insurance business, but he was also a director and treasurer of the White River Savings Bank, director of Hartford National Bank, and director of the Chicago, Kalamazoo & Saginaw Railway. In addition, he was involved in politics, holding a number of different offices. He served as Secretary of Civil and Military Affairs during the administration of fellow Hartford native Governor Samuel E. Pingree, and he was subsequently elected to both houses of the state legislature, along with serving on the state’s Board of Railway Commissioners.

Alfred and Mary Watson had two children. Their son Cedric died in 1890 before his first birthday, but their daughter Margery lived to adulthood. The first photo was taken sometime around the turn of the 20th century, and the 1900 census shows that they were living here with Margery, who was 12 years old at the time, Mary’s father Walter S. Carr, and Alfred’s nephew, Carl W. Cameron. The latter moved out sometime before the 1910 census, but the rest of the family was still here during that year. Walter subsequently died in 1915 at the age of 82, and Margery evidently moved out of the house by the time of her marriage in 1917.

Mary died in 1948 at the age of 83, and Alfred continued to live here until his death in 1950 at the age of 93. They both outlived their daughter Margery, who died in 1940. With no surviving heirs, and with little demand for such a large single-family home during the mid-20th century, the house was ultimately divided into apartments. At some point, the house underwent some significant changes, including the removal of the barn on the left side and the large front porch. Many of its other Victorian-era exterior details are similarly lost, having been replaced by modern siding. Overall, though, the house, which is now known as Hillcrest Manor, is still standing, and it is still recognizable from the first photo. It recently underwent a major renovation shortly before the present-day photo was taken, and it now consists of nine affordable housing units.