The mansion at the corner of Washington and Lynde Streets in Salem, around 1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

Pickman was about 56 years old when he built this house on Washington Street. He apparently lived here for the rest of his life, until his death in 1773, although historical records do not seem to specify. According to these sources, the house was “left by him to his son, Clarke Gayton Pickman,” leaving some ambiguity as to whether he personally lived in this house upon its completion, or simply had it built and then gave it to his son, a practice that was not uncommon among wealthy families of this period.

Either way, his son Clarke (1746-1781) ultimately acquired the house, where he lived with his wife Sarah and their four children. However, he died young, at the age of 35, and his four children had even shorter lives. Both of his sons, Clark and Carteret, died in childhood, and his two daughters, Sally and Rebecca, only lived to be 20 and 28, respectively. Sarah only lived in this house for about a year after Clarke’s death, and sold the property in 1782.

The next owner of this house was Elias Hasket Derby (1739-1799), who was probably the wealthiest of Salem’s many merchants. During the late 18th century, Salem was the seventh-largest city or town in the country, as well as the richest on a per capita basis, and Derby played a large role in this prosperity. The ships of his fleet were among the first American vessels to trade with China, and his shipping empire also included extensive trade with India, Mauritius, Sumatra, Europe, and the West Indies. Some 50 years after his death, he was even referred to as “King Derby” in Nathaniel Hawthorne’s introduction to The Scarlet Letter. In this lengthy polemic against his hometown, Hawthorne laments the decline of the once-prosperous city, equating Derby with the Salem’s golden age.

Upon purchasing this house in 1782, Derby soon set about renovating it. He hired noted local architect Samuel McIntire, who made alterations to the original design. This included the addition of the cupola, which provided Derby with a view of the waterfront and his incoming ships. However, Derby soon began planning for a new house, and in the 1790s he hired Charles Bulfinch to design a mansion a little south of here, on the present-day site of the old town hall. Derby moved into this new house upon its completion in 1799, but he did not get to enjoy it for long, because he died later in the year.

In the meantime, this house on Washington Street was acquired by Derby’s son, John Derby (1767-1831). Like his father, he was also a merchant, but he was involved in other business interests here in Salem, such as the Salem Marine Insurance Company and the Salem Bank. His first wife, Sally, died in 1798, leaving him with three young children. However, in 1801 he remarried to Eleanor Coffin, and the couple had eight children of their own.

Among their children was Sarah Ellen Derby, who married John Rogers and had nine children. Their oldest son, also named John Rogers (1829-1904), was born here in this house, and later went on to become a prominent sculptor. He specialized in small, mass-produced plaster statues, known as Rogers Groups, and these inexpensive pieces of artwork found their way into many homes across the country and overseas.

John Derby died in 1831, and the house was subsequently sold to Robert Brookhouse. It would remain a single-family home throughout the 19th century, although it steadily declined over the years. This reflected the declining prosperity of Salem as a whole, which had peaked in its prominence as a seaport around the turn of the 19th century. It slowly dropped off the list of the ten largest cities in the country, and by the time Hawthorne published The Scarlet Letter in 1850 it had become a shadow of its former glory.

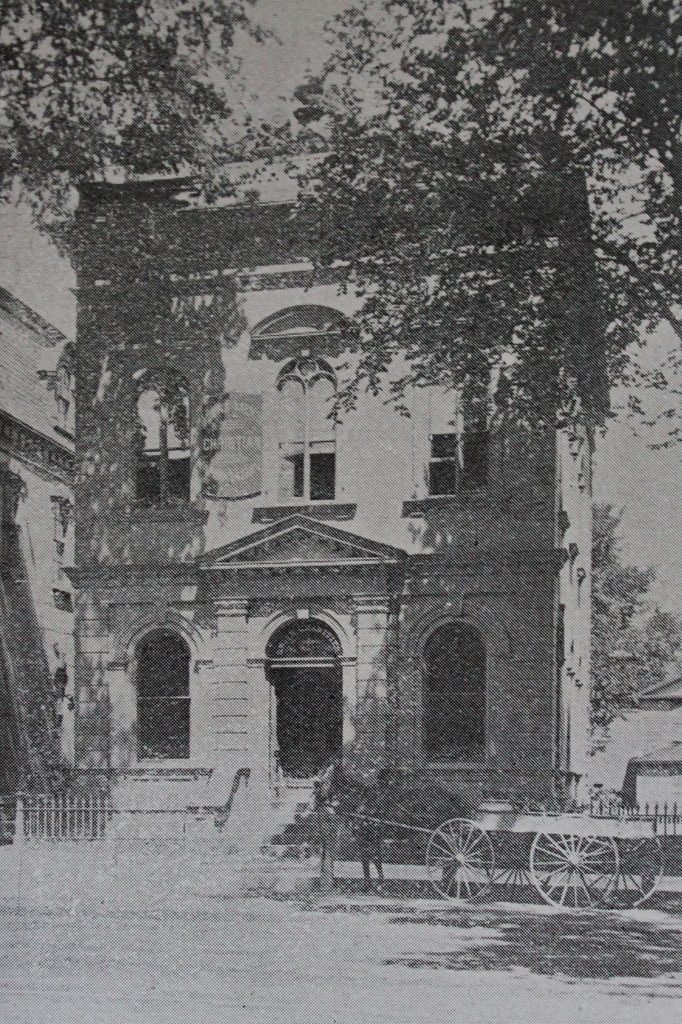

In 1898, the mansion was sold and converted into a commercial property. It became the Colonial House hotel, as shown in the first photo a little over ten years later. The ground floor had two storefronts, with the Colonial House Cafe on the left and a bar on the right. Just to the left of the hotel is a nickelodeon, an early movie theater that, as the signs in front indicate, cost a nickel for admission. These were common during this period, in the early years of film, and the sign above the entrance advertises “Moving Pictures and Illustrated Songs.”

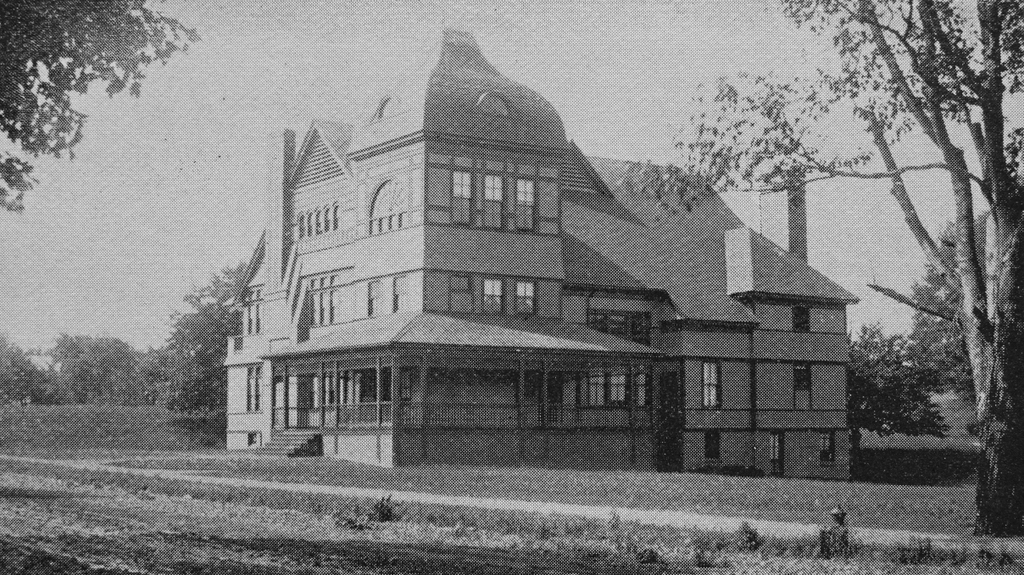

Only a few years after the first photo was taken, the property was sold to the Masonic lodge. The historic 150-year-old mansion was demolished in 1915, and the present-day Masonic Temple was built on the site. This large, Classical Revival-style building was completed in 1916, and featured stores and offices on the lower floors, while the upper floors were used by the Freemasons for office space and meeting rooms. The building was badly damaged by a fire in 1982, which caused over a million dollars in damage to the upper floors, but it was subsequently restored and is still standing. Along with the other nearby buildings, it is now part of the Downtown Salem Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.