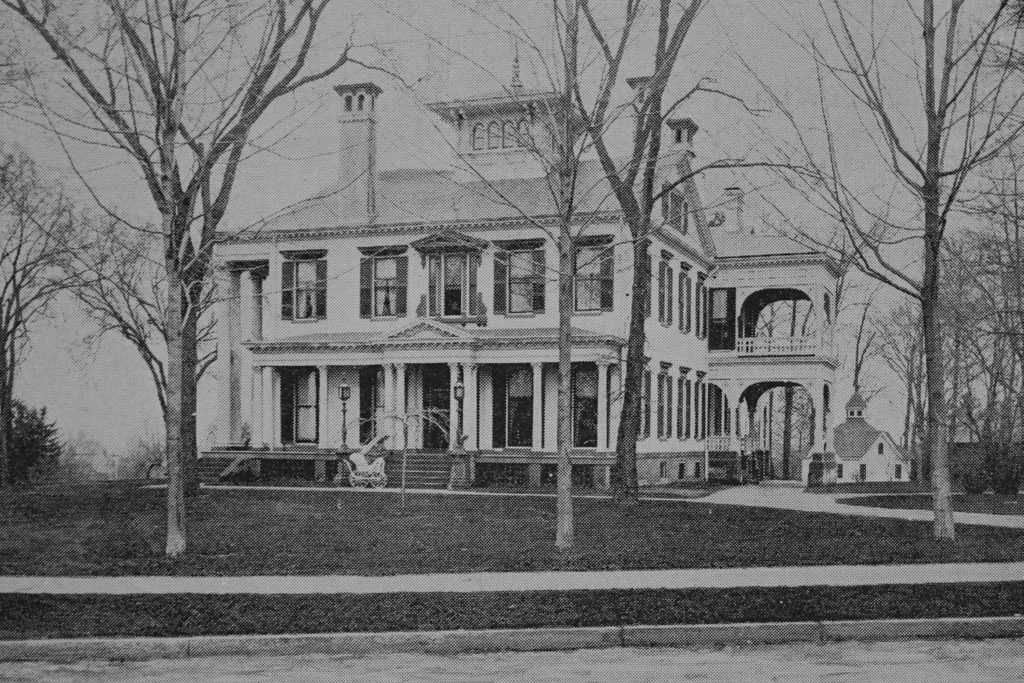

The house at 398 Maple Street in Springfield, around 1893. Image from Sketches of the old inhabitants and other citizens of old Springfield (1893).

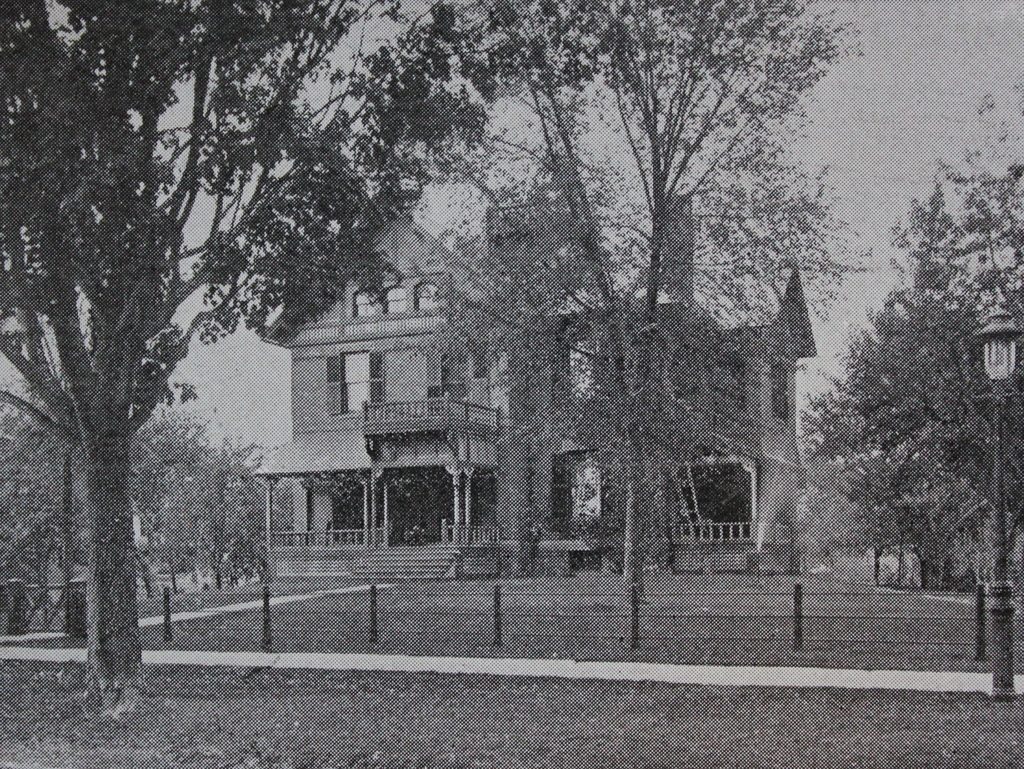

The scene in 2017:

This house was built in 1828 by David Ames, Sr., a prominent paper manufacturer who had previously served as the first superintendent of the Springfield Armory, from 1794 to 1802. He lived in a modest house nearby on Mill Street, at the foot of Maple Street, but in the mid-1820s his son, David Ames, Jr., built a large mansion atop the hill on Maple Street, which came to be known as Ames Hill. Shortly after, in 1828, David Ames, Sr. built this architecturally-similar house for his son John, who was about 28 years old at the time.

John was, along with his brother David, involved with their father’s paper company, and he invented and patented a number of papermaking machines. However, he never actually lived here in this house. It was completed around the same time that he was engaged to be married, and he was supposed to live here with his new wife. The wedding ultimately did not happen, though, and John remained a lifelong bachelor, living in his father’s house on Mill Street until his death in 1890.

In the meantime, this house remained vacant for many years. The grounds occupied the entire triangle of land between Mill, Pine, and Maple Streets, and the house would have been easily visible up the hill when looking out the front windows of the Ames house on Mill Street. Although vacant, it was owned by the Ames family until 1856, when it was sold to Samuel Knox, a lawyer and politician from St. Louis.

Originally from Blandford, Massachusetts, Samuel Knox graduated from Williams College and Harvard Law School, and subsequently moved to St. Louis, where he established his law practice in 1838. He continued to live in Missouri for many years, but in 1856 he purchased this house as a summer residence, and owned it until 1869. During this time, he ran for Congress in 1862, in Missouri’s first congressional district. He lost to incumbent Francis Preston Blair, Jr., but Knox contested the results, and in 1864 he was declared the winner, with less than nine months remaining in his term. He served the rest of his term, but lost re-election in 1864 and subsequently returned to his law practice. He sold this house a few years later, but he would eventually move back to Massachusetts permanently, living in his native Blandford until his death in 1905, and he was buried only a short distance away from here in Springfield Cemetery.

In 1869, this house was purchased by George R. Dickinson. Like the original owner of the house, he was a paper manufacturer, and ran the George R. Dickinson Paper Company in Holyoke. Born and raised in Readsboro, Vermont, Dickinson later moved to Holyoke, and in 1859 he married his first wife, Mary Jane Clark. They had one child, Henry Smith Dickinson, who was born in 1863, but Mary died several days later. The following year, George remarried to Mary’s sister, Harriet, and they had a son, George R. Dickinson, Jr., who was born around the same time that the family moved into this house.

The younger George drowned in 1876 at the age of seven, but his older half brother Henry grew up here in this house, and eventually joined his father in the paper business. Upon George’s death in 1887, Henry inherited this property and also became president of the George R. Dickinson Paper Company. He remained in this role until 1899, when Dickinson Paper was acquired by the American Writing Paper Company, with Henry becoming the company’s vice president.

Along with his involvement in the paper industry, Henry was also active in politics. In 1884, he served as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, and he was also chairman of the Republican City Committee here in Springfield. He subsequently served as a city alderman in 1889 and as president of the board of alderman in 1890, and he served one term each as a state representative in 1891 and mayor of Springfield in 1898.

When the first photo was taken around 1893, Henry and his wife Estella were living here in this house along with his stepmother Harriet. However, in 1894 Harriet remarried, and by the following year Henry and Estella had house of their own at 192 Pearl Street. In the meantime, Harriet and her second husband, William W. Stewart, remained here in this house. However, Estella died in 1902, and he subsequently remarried to his second wife Agnes. By the 1910 census Henry had returned to this house, where he was living with William, Harriet, Agnes, and the four children from his first marriage: George, Henry, Stuart, and Harriet.

Henry died in 1912, and Harriet in 1915, but the house was still in the family as late as 1919, when Henry’s three sons were living here. However, by the early 1920s the house was the home of George A. MacDonald, the president of the Chicopee National Bank. He was living here as late as the mid 1920s, but by the end of the decade the house was being rented by George W. Ferguson, the pastor of St. Peter’s Episcopal Church. During the 1930 census, he and his wife May were living here with May’s three teenage sons from her first marriage, along with four servants.

The Fergusons were living here as late as 1933, but by the following year the house was listed as vacant in the city directory. It was evidently demolished soon after, because it does not appear in late 1930s directories or in the WPA images of Maple Street, which were done in 1938-1939. The site was subsequently redeveloped, and it is now the site of a Colonial Revival-style Mormon church, which was built in 1957. There is no longer any trace of the old house here in his scene, but at least one thing from the first photo is evidently still in existence. The carriage house, barely visible in the distance to the right of the house in the first photo, was apparently moved to East Forest Park and converted into a residence, where it still stands at the corner of Ellsworth Avenue and Gifford Street.