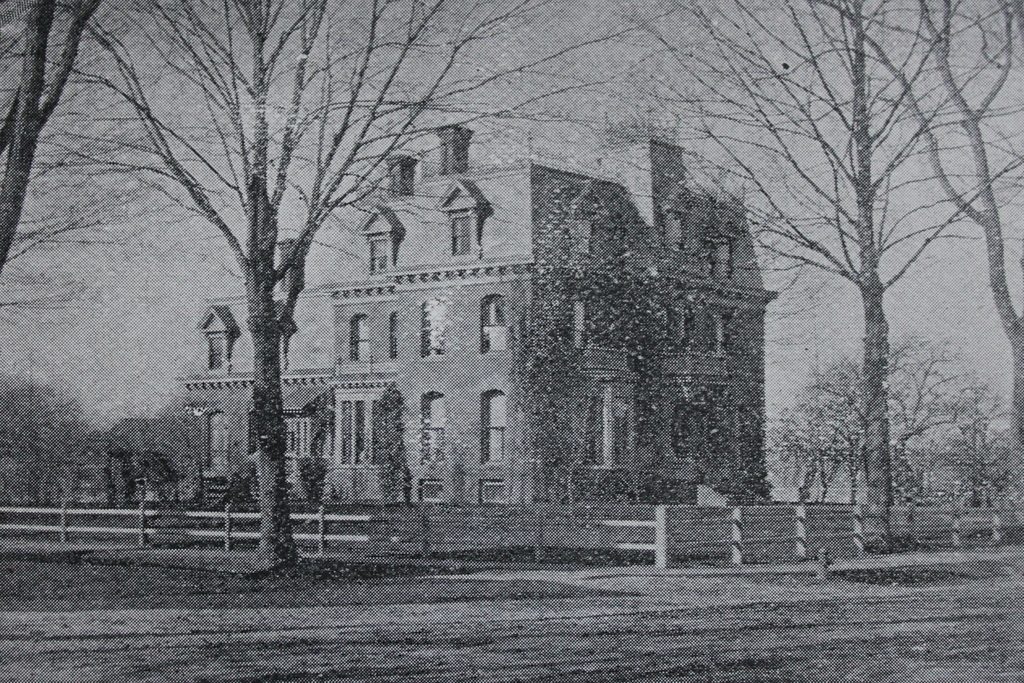

The house at 104 Springfield Street, at the corner of Howard Street in Chicopee, around 1892. Image from Picturesque Hampden (1892).

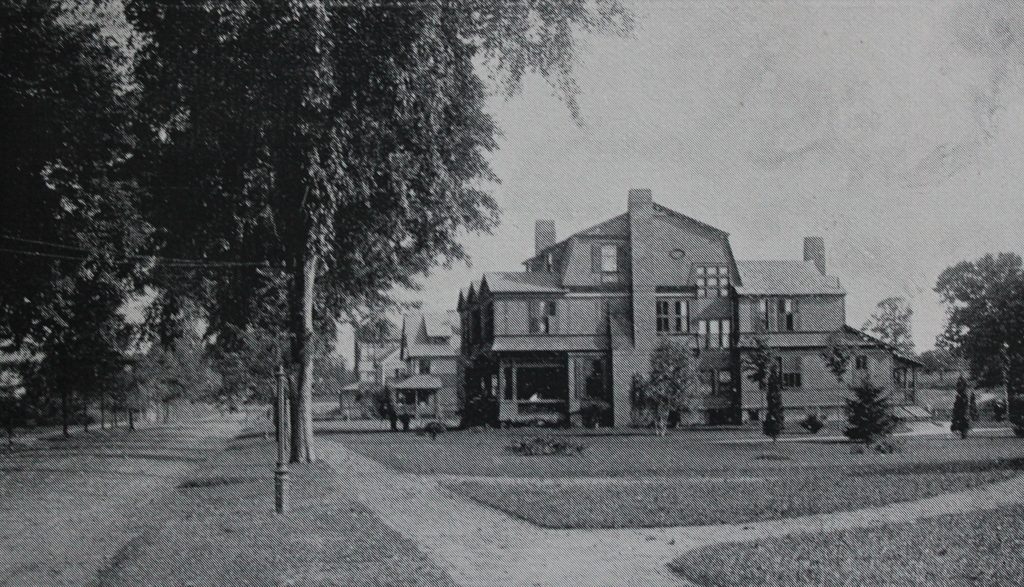

The house in 2017:

This elegant Second Empire-style House was built around 1869, and was originally the home of businessman D. Frank Hale. Variously listed in censuses and city directories as a real estate broker, a merchant, and a landlord, he was evidently prosperous, because the 1870 census lists his real estate as being worth $88,500, plus $5,500 in his personal estate, for a total net worth equal to over $1.8 million today. However, despite this wealth his personal life was marred by tragedy. He and his wife Lucy had six children, but only one of them, their son William, survived to adulthood. Their other five children died of various diseases when they were six years old or younger, including 3-month-old twin boys Arthur and Luther, who died of “brain fever” ten days apart from each other in March 1872.

The Hale family lived here until about 1878, when they moved to Springfield. They sold the house to George D. Robinson, a lawyer and politician who was, at the time, serving his first term in Congress. Born in Lexington in 1834, Robinson moved to Chicopee in 1856 after his graduation from Harvard. Here, he worked as principal of Chicopee’s Center High School from 1856 to 1865, and subsequently became a lawyer and entered politics. He represented Chicopee in both the state House of Representatives and the state Senate, and in 1876 he was elected to the U. S. House of Representatives, where he served from 1877 to 1884.

In 1883, Robinson ran as the Republican candidate for governor of Massachusetts, defeating incumbent governor Benjamin Butler in a hotly contested general election. Butler, himself a former Congressman, had been a notoriously inept general during the Civil War, but he had presidential ambitions and hoped that his re-election as governor would help earn him the Democratic nomination in 1884. However, Butler’s loss to Robinson, after just a single one-year term as governor, significantly hurt his chances, and the 1884 Democratic nomination – and ultimately the presidency – went to another northeastern governor, Grover Cleveland of New York.

Robinson served three one-year terms from 1884 to 1887, and was involved in the passage of several key reforms, including free textbooks for public school students, as well as a law mandating employers to pay their workers on a weekly basis. However, he declined to seek a fourth term in the 1886 election, and retired from politics. He returned to his private law practice, and his work included several high-profile cases. Most notably, he was one of the defense attorneys for Lizzie Borden, the Fall River who was tried, and ultimately acquitted, for the 1892 axe murders of her father and stepmother.

George Robinson’s first wife, Hannah Stevens, died in 1864. Three years later, he remarried to Susan Simonds, and by the time they moved into this house in they late 1870s they had one child, Annie, plus George’s son from his first marriage, Walter. George and Susan were still living here when the first photo was taken in the early 1890s, and he would remain here until his death in 1896. Susan was still living here during the 1900 census, along with her sister Caroline, but she later moved to Springfield, where she died in 1909.

In 1917, this house was sold to the Roman Catholic Church, becoming the rectory for the Assumption Church, a predominantly French-Canadian parish that served some of the many factory workers who had immigrated to Chicopee from Quebec. About five years later, a new church building was completed just to the north of the house, on the right side of the photo, and both it and the rectory remain in use today.

Nearly 150 years after it was built, Governor Robinson’s former house remains as one of the finest 19th century homes in Chicopee, and has been well-preserved over the years. There have been a few minor changes since the first photo was taken, such as the small one-story addition on the left side, but overall it remains in excellent condition, all the way down to fine details such as the iron balustrades on the roof. Today, both the house and the Assumption Church form part of the Springfield Street Historic District, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.