Looking west on the New Haven Green, toward Trinity Church on the Green, with the Old Campus of Yale University in the distance, around 1900-1915. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The scene in 2018:

The New Haven Green is home to three historic churches on the west side of Temple Street, all of which were constructed between 1812 and 1816. The two oldest, Center Church (1814) and United Church (1815) both feature Federal-style architecture that was common for churches of this period, and Center Church is particularly notable for having been designed by prominent architects Asher Benjamin and Ithiel Town. Town subsequently designed the last of these three churches, Trinity Church, which was completed in 1816 on the corner of Temple and Chapel Streets. However, its design was a vast departure from his work on Center Church, and it is generally regarded as one of the first – if not the first – Gothic-style church building in the country, as Gothic Revival architecture would not gain widespread popularity for several more decades.

Trinity Church was established in 1723, and was a rare Anglican parish in a colony that was otherwise predominantly Congregationalist. The first permanent church building was completed in 1753, and stood a block away from here on the southeast corner of Chapel and Church Streets. As time went on, though, this building proved too small for the growing parish, and in 1814 construction began on a new church here on the Green. The exterior was built of locally-quarried trap rock from East Rock, giving the church its distinctive multicolor appearance. This, along with the Gothic architecture, provided a significant contrast to the more conventional brick churches just to the north of here. The new church was consecrated in 1816, an event that coincided with the installation of a new rector, the noted journalist, author, and clergyman Harry Croswell.

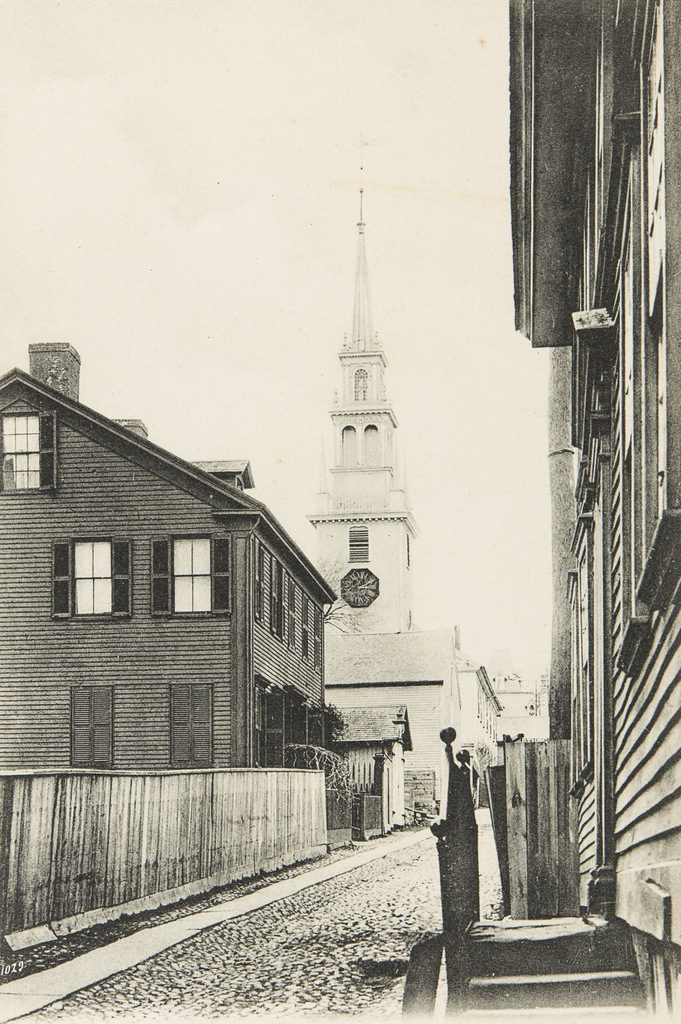

By the time the first photo was taken in the early 20th century, Trinity Church was already nearly 100 years old, and had undergone some changes since its completion. The top of the tower was originally constructed of wood, but this portion was rebuilt of stone in 1871. The church had also been built with crenelated wood balustrades along the roofline, although these rotted and were eventually removed as part of the 1871 renovations. Other 19th century changes included the installation of stained glass windows, and the addition of a pyramidal spire atop the tower, which can be seen in the first photo.

In more than a century since the first photo was taken, the interior of the church has undergone some changes, but this view of the exterior has remained largely unaltered, with the only noticeable difference being the removal of the pyramid on the tower. Trinity Church is still an active Episcopalian parish, and the church building is now part of the New Haven Green Historic District, which includes the other two early 19th century churches nearby. Aside from the church itself, there have not been many other changes to the scene from the first photo. The New Haven Green still functions as a park in the center of the city, and the Old Campus of Yale University still stands in the distance, on the other side of College Street. The only significant difference in this view of the campus is the loss of Osborn Hall. Visible just to the right of the church, it was demolished in 1926 and replaced by Bingham Hall, which now stands on the site.