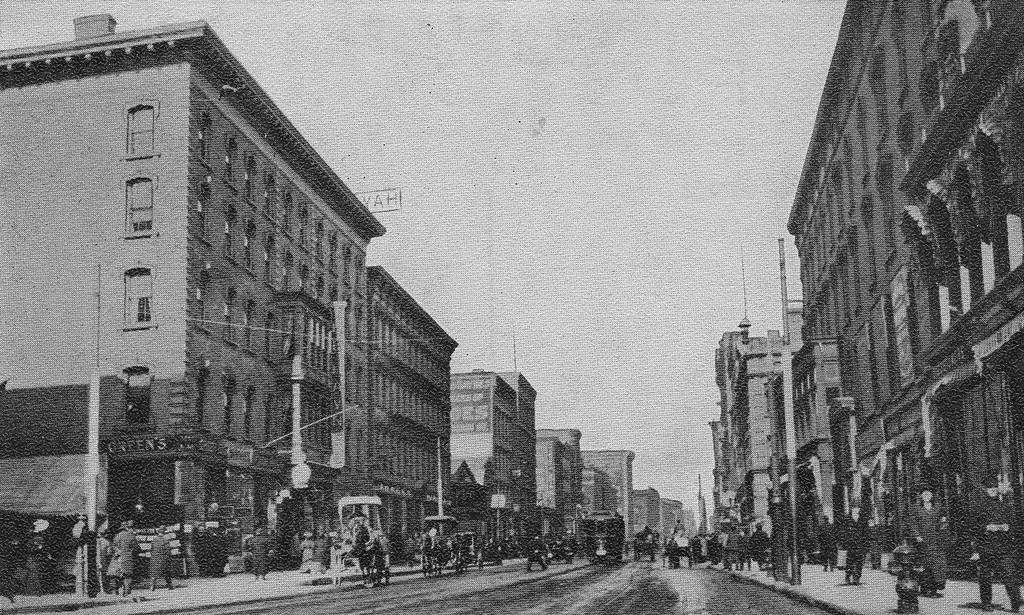

The National Guard Armory at the corner of Sargeant and Pine Streets in Holyoke, around 1907-1910. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

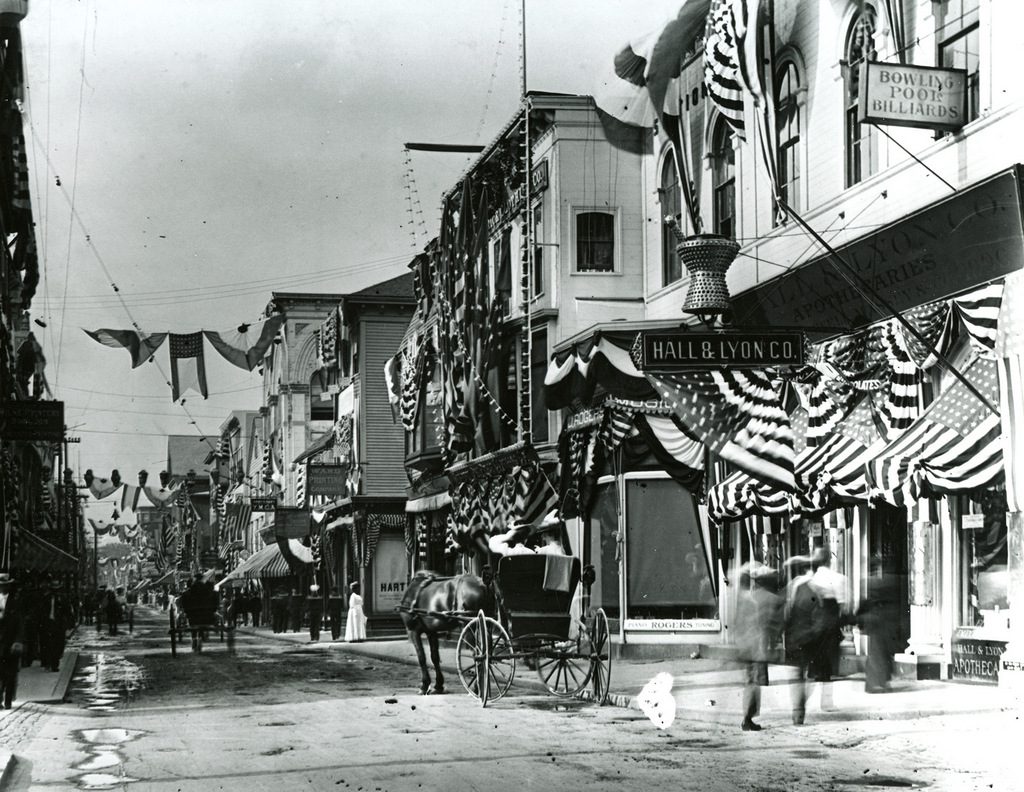

The building in 2017:

Around the turn of the 20th century, the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia – later known as the Massachusetts National Guard – built a number of similar, castle-style armories across the state, including ones in Boston, Springfield, and Worcester. The armories were designed to look imposing, and to represent the strength of the state militia, but the architecture was not entirely for looks. At least in the case of the Boston armory, the building was designed to withstand riots and other civil unrest, and its tower could be used to transmit signals to government leaders at the State House.

Here in Holyoke, the armory was smaller than those in the larger cities, but it had similar architecture, with turrets, narrow windows, and a crenellated parapet atop the building. It was designed by local architect William J. Howe and completed in 1907, and was supposedly based on the design of the 18th century Hawarden Castle in Wales. The building included the castle-like structure in the front, along with a drill hall in the back, and it was the home of the 1st Battalion, 104th Infantry Regiment. Only about a decade after the first photo was taken, the 104th Infantry went on to serve with distinction during World War I, suffering heavy casualties and earning the Croix de Guerre from the French government, marking the first time that an American military unit was honored for bravery by a foreign country.

The armory remained in use for much of the 20h century, and in 1990 it took on an usual role as a temporary prison. At the time, the old York Street Jail in Springfield was dangerously overcrowded, to the point where inmates were being released early in order to make room for newly-convicted prisoners. Despite pleas from Hampden County Sheriff Michael Ashe, county and state officials were slow in responding to the problem, so in February 1990, Ashe took a dramatic step to call attention to the situation. Invoking an obscure 1696 state law that empowered sheriffs to do whatever was necessary to restore order in times of “imminent danger of a breach of the peace”, Ashe commandeered the National Guard armory in Springfield, over the objections of the armory commander, and housed 17 prisoners in the facility.

The bold move quickly gained the attention of state officials, and the news story made headlines across the country. Although Ashe was threatened with criminal trespass charges, a judge ruled that the prisoners could remain in the armory, and the state soon made arrangements for the prisoners to be moved here to the Holyoke armory. The building served as a prison annex for most of 1990, housing nearly 70 inmates, but it had to close in late November after governor Michael Dukakis refused to provide more funding. This closure required the early release of dozens of convicts, but the armory annex was reopened the following year when the newly-elected governor, Bill Weld, authorized funding.

The armory would remain in use as a jail annex until 1992, when the current Hampden County House of Correction opened in Ludlow. The historic building has remained vacant since then, and it is now owned by the city. Over the years, it has been the subject of various redevelopment proposals, but none have come to fruition and the building has steadily deteriorated. In early 2016, the drill shed in the rear of the building collapsed, requiring emergency demolition of the ruins. The front portion of the building survived the collapse, and it is still standing, but it is still vacant, despite efforts by the city to find a buyer for the property.