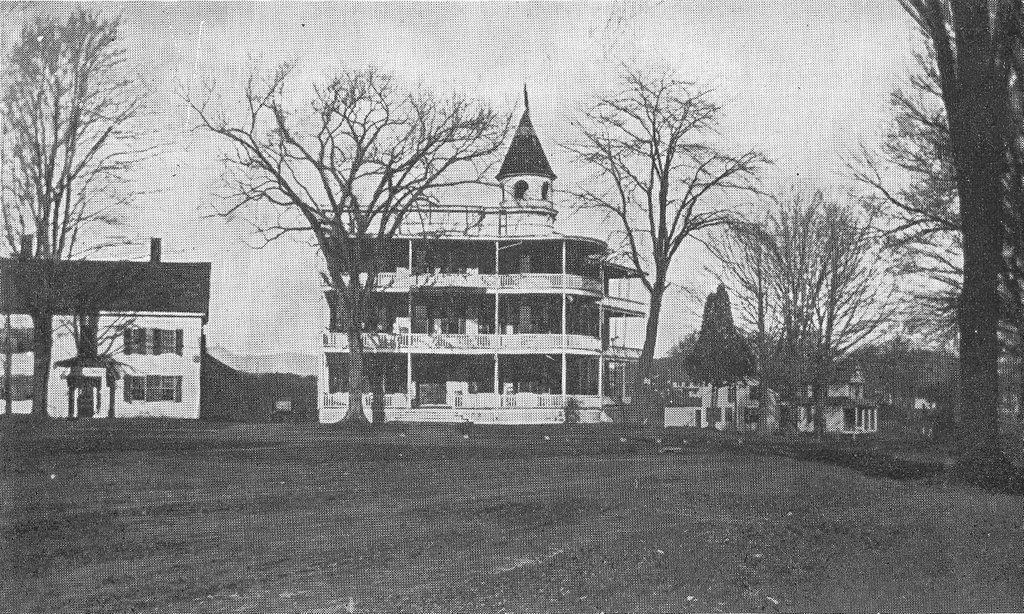

The Longfellow House on Brattle Street in Cambridge, around 1910-1920. Image courtesy of the Library of Congress, Detroit Publishing Company Collection.

The house in 2019:

This elegant Georgian-style mansion was built in 1759 as the home of John Vassall, a wealthy young man whose family owned a number of sugar plantations in the Caribbean. Vassall was born in 1738, but his mother died just a year later, and his father died when he was only nine. As the only son, he inherited his father’s wealth, and he was subsequently raised by his grandfather Spencer Phips, the longtime lieutenant governor of colonial Massachusetts.

His inheritance had included 56 acres of land here in Cambridge, and he wasted little time in improving the property after coming of age. In 1759, at the age of 21, he had his father’s old house demolished, and he replaced it with this home here on Brattle Street, located about a half mile west of the center of Cambridge. Two years later, he married Elizabeth Oliver, whose brother Thomas later served as the colonial lieutenant governor. The couple went on to live here until 1774, and during this time they had seven children, one of whom died in infancy.

The Vassalls lived here at a time when slavery was still legal in Massachusetts. Although slavery was not widespread in the colony, it was not uncommon for wealthy families to have several enslaved domestic servants. In the case of the Vassalls, though, they had at least seven slaves living here at this house, which was an unusually large number for colonial Massachusetts. This reflected the significant wealth of the Vassall family, which itself was largely derived from enslaved labor on the family’s sugar plantations.

As both the grandson and brother-in-law of high-ranking royal officials, as well as being a wealthy landowner with holdings in other colonies, John Vassall remained loyal to the British crown in the years leading up to the American Revolution. However, as tensions escalated by the mid-1770s, the Vassalls decided to relocate to the relative safety of Boston, leaving their country estate here in Cambridge in the care of their slaves. They intended to return once the situation improved, but they ultimately evacuated Boston with the rest of the British fleet in March 1776. They made their way first to Halifax and then to England, where they continued to prosper despite having all of their Massachusetts property confiscated.

In the meantime, while the Vassalls were still residing in Boston, Cambridge became the main encampment of the Continental Army, thanks to its location directly across the Charles River from Boston. From here, the army laid siege to Boston, confining the British to what was, at the time, a geographically small seaport town on a narrow peninsula in the middle of the harbor. At the start of the siege in the spring of 1775, the colonial forces consisted primarily of local militia companies, but on June 14 the Continental Congress in Philadelphia established the Continental Army, and a day later Virginia delegate George Washington was appointed as its commander-in-chief.

Washington arrived in Cambridge on July 2, and he initially set up his headquarters at the Wadsworth House, which was the residence of the Harvard president. He stayed there for two weeks, but on July 16 he moved here to the vacated Vassall house. This move was likely motivated in part by the fact that, at the previous house, he had to share space with General Charles Lee, and also with the Harvard president. The Vassall house was also a quieter place, further from the town center and away from the main army encampments, and Washington may have also preferred it because, in part, it resembled his own home in Virginia. Like Mount Vernon, the house was situated on a large estate, surrounded by farmland tended by slaves, and it likewise offered a view of a major river, in this case the Charles River.

Whatever his reasons for choosing this house, the George Washington who arrived here in July 1775 was in many ways very different from the man who would ultimately come to be known as the father of his country. Although widely respected and celebrated with enthusiasm here in Cambridge, Washington was still a relatively young man at 43. Up to this point, his military career was limited to serving as a colonel in the Virginia militia during the French and Indian War. His wartime service had been distinguished but not overly remarkable, yet by the summer of 1775 he was viewed by many patriots as the best choice to lead the newly-organized army.

This house served as Washington’s residence and headquarters throughout the rest of the siege of Boston, until after the British evacuated the town in March 1776. During this time, the house was a busy place, with Washington regularly receiving high-ranking officers and other important visitors. For a time, General Horatio Gates also lived here, and Martha Washington arrived here to live with her husband in December 1775. In addition, Washington’s councils of war were held here, probably in the dining room, which was apparently located in the front room on the right side of the house. These meetings were attended by his top generals, including such notable figures as Artemas Ward, Charles Lee, Israel Putnam, and Nathanael Greene.

It was also here at this house that, in the fall of 1775, Washington received a poem written by Phillis Wheatley. A few years earlier, while still enslaved, she had become the first published African American poet in the American colonies. By 1775 she had gained her freedom, and she continued to write poems, many of which gave praise to notable public figures. In her poem to Washington, she described the conflict between Britain and the colonies, and wrote in glowing terms about Washington being “first and place and honours,” and “Fam’d for thy valour, for thy virtues more,” before concluding with four lines that foreshadowed his future as the leader of the new country:

Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side,

Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide.

A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine,

With gold unfading, Washington! be thine.

Washington did not immediately respond to Wheatley, but in early 1776 he finally wrote back to her, praising her abilities by writing, “I thank you most sincerely for your polite notice of me, in the elegant Lines you enclosed; and however undeserving I may be of such encomium and panegyrick, the style and manner exhibit a striking proof of your great poetical Talents.” Then, in a rather remarkable offer for a southern slaveowner to extend to a recently-emancipated slave, Washington invited Wheatley to visit his headquarters, writing “If you should ever come to Cambridge, or near Head Quarters, I shall be happy to see a person so favoured by the Muses, and to whom Nature has been so liberal and beneficent in her dispensations.” Whether or not Wheatley actually visited him here is unknown; it is possible that she may have, but if so there are no surviving contemporary accounts of it.

During his time in Cambridge, Washington did not fight any major battles, although the idea of assaulting British-occupied Boston was a frequent topic of discussion here at his councils of war. In the end, though, the decisive move that ended the siege of Boston came on March 4, 1776, when the Continental Army, in the course of a single night, secretly fortified Dorchester Heights to the south of Boston.

The cannons on the hill made the British position in Boston untenable, forcing their commander, General William Howe, to choose between abandoning the town or risking a Bunker Hill-style assault on Dorchester Heights. He considered the latter option, and Washington was actually counting on this, as he hoped to attack Boston from Cambridge while the majority of Howe’s army was at Dorchester. However, Howe ultimately decided to evacuate Boston, and Washington allowed his fleet to sail away unharmed under the condition that the British not burn the town.

The British sailed away on March 17, on a day that is still celebrated in Boston as Evacuation Day. Washington remained here at his headquarters for the next few weeks, before leaving on April 4. He and his army would subsequently head south to New York City, to defend it from an anticipated attack by Howe’s army. The remainder of 1776 would prove to be a difficult time for Washington, who suffered a series of defeats in the late summer and fall. These were “the times that try men’s souls,” as Thomas Paine put it, and after his success here in Boston, Washington would not experience another major victory until Trenton in late December. Still, despite these difficulties, Washington maintained the respect of the majority of his soldiers, and his leadership would prove instrumental in the ultimate success of the American Revolution.

In the meantime, after Washington’s departure the house had several different owners in the late 18th century. Merchant Nathaniel Tracy owned it from 1781 to 1786, and then another merchant, Thomas Russell, owned it until 1791, It was then purchased by Andrew Craigie, a noted apothecary who had served as the first Apothecary General of the Continental Army during the American Revolution. He married his wife Elizabeth in 1793, and he lived here until his death in 1819. During this time, he improved the house and the surrounding grounds, and he frequently held lavish parties here, with attendees such as Prince Edward, who was the father of Queen Victoria.

After Craigie’s death, his widow Elizabeth continued to live here for the rest of her life. In order to reduce her expenses, she took in boarders during much of this time. These included historian Jared Sparks, politician Edward Everett, and most notably, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. He was a 30-year-old Harvard professor when he moved into a room here in 1837, and he had recently been widowed after the death of his young wife Mary less than two years earlier.

At the time, Longfellow had barely begun his literary career. His first book, Outre-Mer, had been published in 1835, but it was here in this house that Longfellow would establish himself as one of the leading writers of 19th century America. His next major works, the novel Hyperion and poetry collection Voices of the Night, were written here, and were published in 1839. Around this time, he was courting Fanny Appleton, the daughter of prominent merchant Nathan Appleton. He and Fanny ultimately married in 1843, two years after the death of Elizabeth Craigie, and Appleton purchased the house from her heirs as a wedding gift for Longfellow.

Henry and Fanny Longfellow both lived here for the rest of their lives, and during this time they had six children, one of whom died young. He wrote most of his works here, including his famous epic poems Evangeline and The Song of Hiawatha, along with notable shorter poems such as “Paul Revere’s Ride” and “The Village Blacksmith.” However, this house was also the site of a tragedy when, in 1861, Fanny died from severe burns after her dress caught on fire. Henry was also badly burned while trying to extinguish the flames, and this resulted in him growing his famous beard in order to hide the scars on his face.

Because Longfellow was such a famous literary figure during his lifetime, he frequently received notable guests here at his house. He had a close friendship with Senator Charles Sumner, who was a frequent visitor here. Other prominent local visitors included Ralph Waldo Emerson and Nathaniel Hawthorne, along with foreigners such as British novelists Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, Swedish singer Jenny Lind, British actress Fanny Kemble, Irish playwright Oscar Wilde, and Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil. Dickens actually visited the house several times in November 1867 during his American tour, including for Thanksgiving dinner on November 28.

Longfellow died in 1882 at the age of 75, after having lived here for 45 years. The house would remain in his family for many more years, though, and his daughter Alice was still living here when the first photo was taken around the 1910s. She was 59 years old when the 1910 census was taken, and she was listed as living here alone except for three servants. Alice was involved in a number of philanthropic causes and historic preservation efforts, including working with other family members to establish the Longfellow House Trust, which preserved the family home and its contents.

The Longfellow House Trust continued to maintain the house long after Alice Longfellow’s death in 1928, and in 1962 the house was designated as a National Historic Landmark. Then, ten years later, the organization donated it to the National Park Service. The property became the Longfellow National Historic Site, and it has been open to visitors ever since, although in 2010 it was renamed the Longfellow House–Washington’s Headquarters National Historic Site. Today, very little has changed in this scene since the first photo was taken more than a century ago, and it survives not only as an excellent example of colonial-era Georgian architecture, but also as an important connection to both George Washington and to Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.